February 21 Marks 53 Years Since the Death of Malcolm X: A Martyr in the Fight for Anti-Racism

Malcolm X knew he was going to die.

He told his biographer Alex Haley, “each day I live as if I am already dead … I do not expect to read this book in its finished form.” His foreboding was timely – he and his family narrowly escaped with their lives when their home in Queens, New York was bombed on February 14, 1965. He suspected either the Nation of Islam or the Ku Klux Klan to be responsible, but no culprit was ever identified.

The day after the bombing, X traveled to Detroit, Michigan for a speaking engagement undeterred by escalating threats. He apologized to the audience for his appearance, disclosing that the disheveled clothes he had on were the only clothes he had when he fled his home. He also addressed rumors about his former mentor, Elijah Mohammed, speculating that the Nation of Islam wanted him silenced. He declared “they certainly can’t frighten me.”

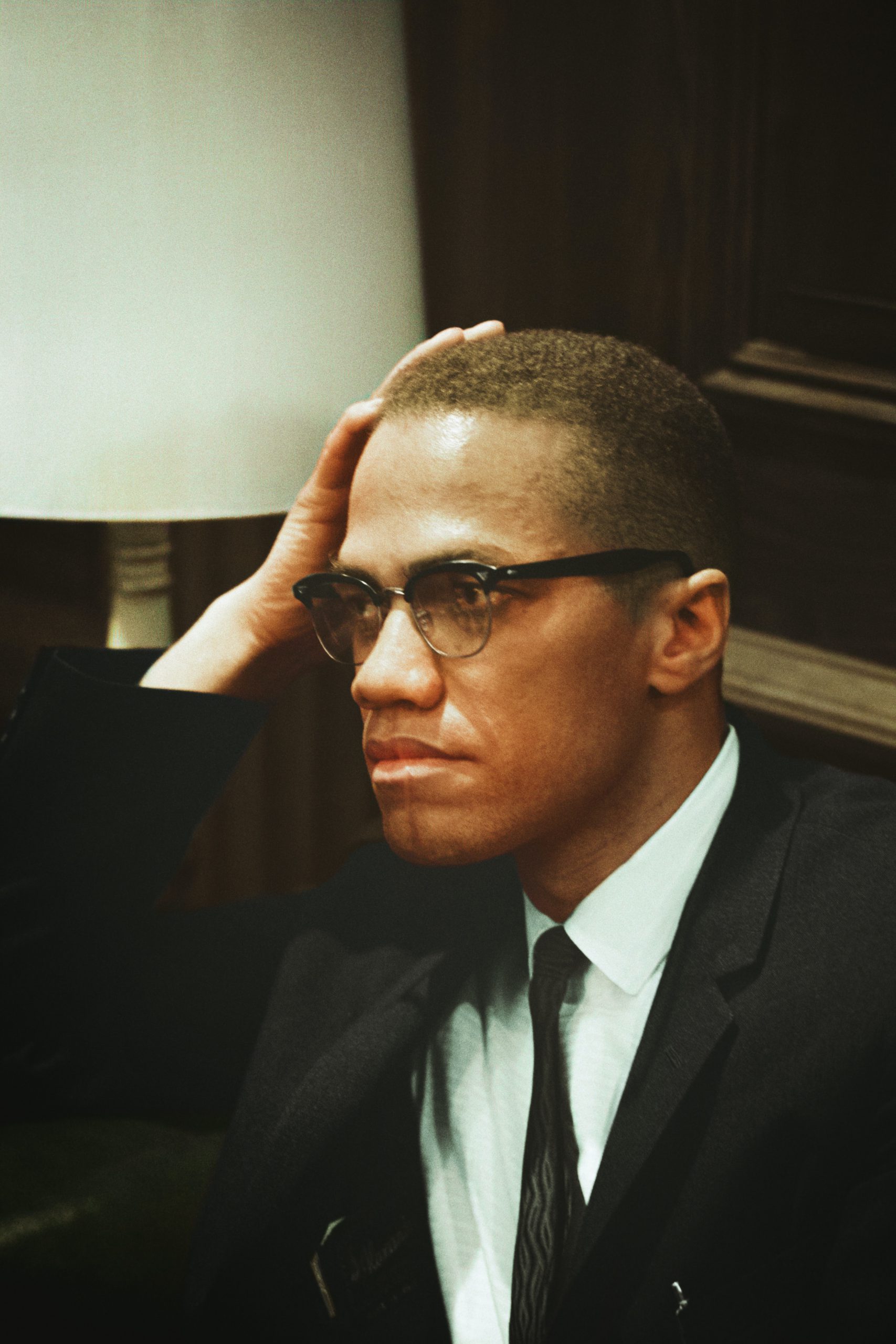

Mainstream media frequently portrayed Malcolm X as a dangerous charlatan because of his calls for self-defense and justice “by any means necessary.” While this view contrasted with the non-violent direct-action sect of the civil rights movement, it was hardly radical. After he was killed, however, Time Magazine described X as “an unashamed demagogue” with a gospel of hatred and creed of violence who, in his assassination, was reaping what he sowed. Similarly, the New York Times’ coverage focused on his criminal past and described him as having a “cold fury” lurking behind his horn-rimmed glasses.

“That’s our motto. We want freedom by any means necessary. We want justice by any means necessary. We want equality by any means necessary.”

Malcolm X

But Malcolm X advocated for brotherhood and unity, not violence. In 1964, he created the Organization of Afro-American Unity (OAAU), an organization with the goal of unifying the African and African American communities against global oppression. In this way, he fought in an ideological war using ideas rather than weapons. The last few months of his life were dedicated to internationalizing the Black civil rights movement into a global struggle for human rights:

“We are resolved to reinforce the common bond of purpose between our people by submerging all of our differences and establishing a nonsectarian, constructive program for human rights. […] but it’s an organization of American-American unity in the sense that we want to unite all of our people who are in North America, South America, and Central America with our people on the African continent. We must unite together in order to go forward together. Africa will not go forward any faster than we will and we will not go forward any faster than Africa will. We have one destiny and we’ve had one past.”

I cannot help but wonder what would have become of Malcolm X’s new international approach and what he would have been able to achieve at home and abroad if he had lived long enough to see his vision through completion.

Malcolm X was fully aware of the public persona he created and its consequences. He understood the personal implications for acting as a gadfly to highlight the shortcomings of American society. He knew that as in war, a soldier in the battle of ideas ran a risk of dying for the cause, and he was fully prepared to do so:

“I know that societies often have killed the people who have helped to change those societies. And if I can die having brought any light, having exposed any meaningful truth that will help to destroy the racist cancer that is malignant in the body of America – then all the credit is due to Allah. Only the mistakes have been mine.”