BY DAVID PAYNE

Within 50 years, human beings will go on one-way journeys to permanent settlements on Mars.

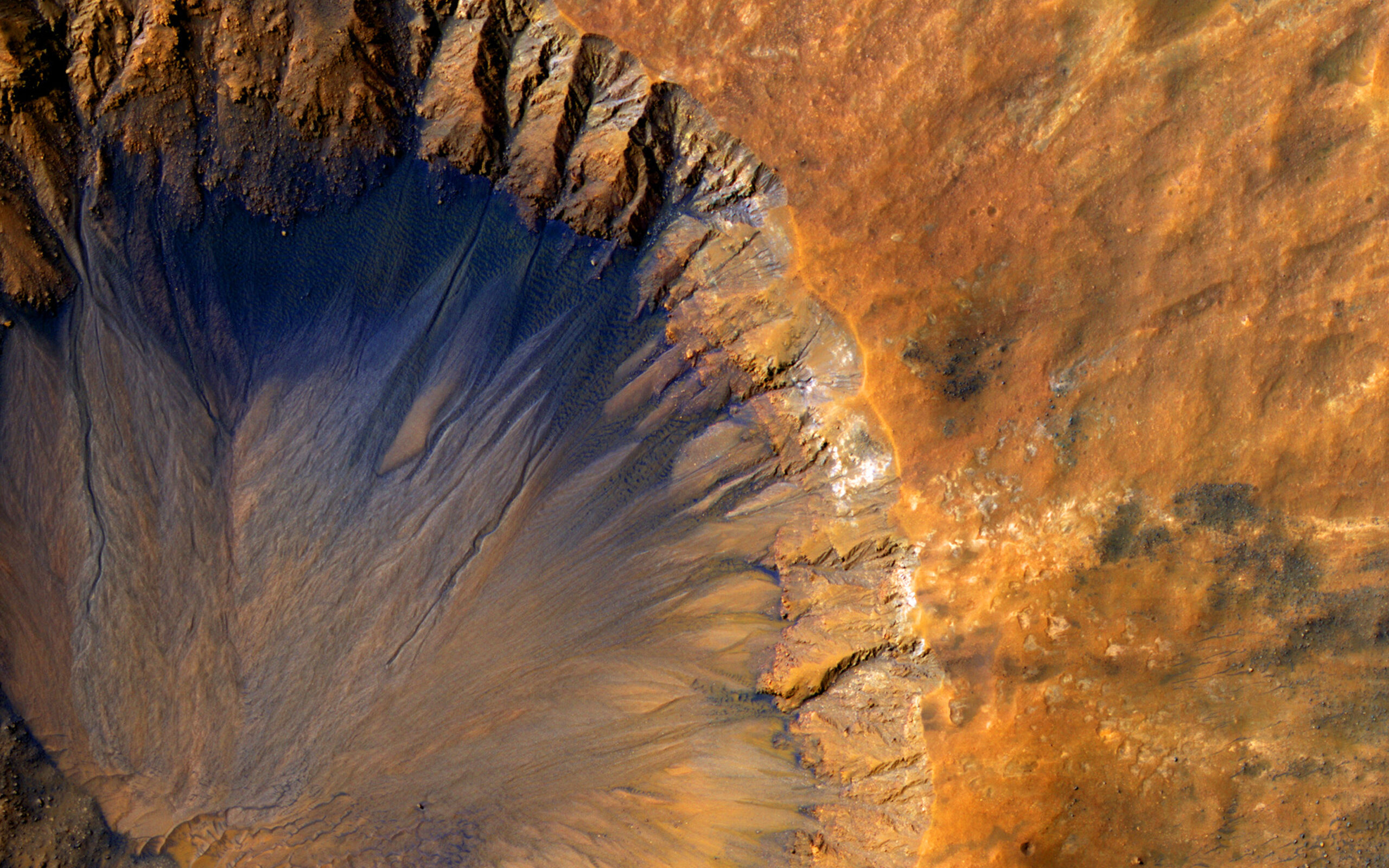

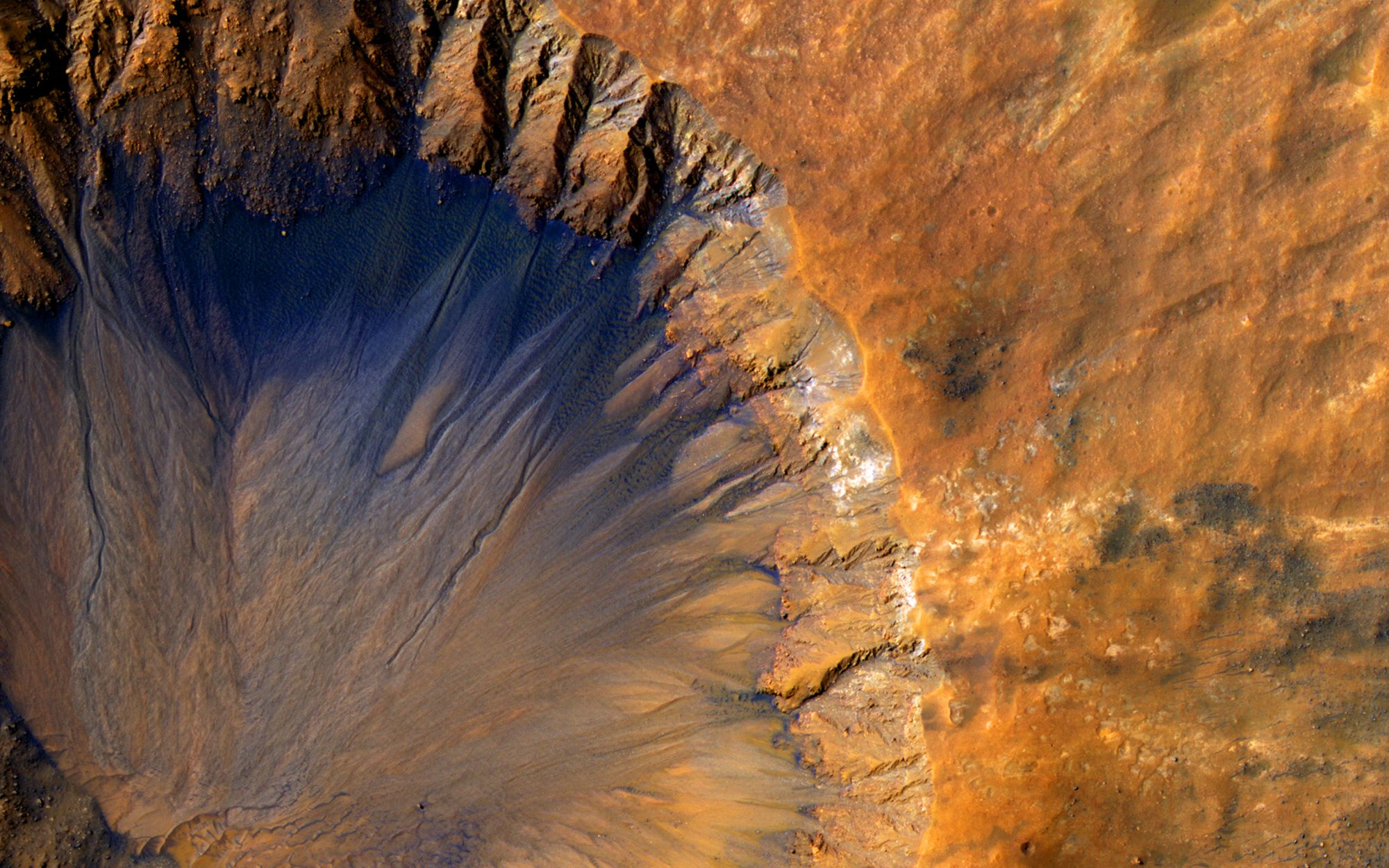

That claim is audacious but is being increasingly echoed by the likes of Elon Musk and supported by the plans of various companies, governments, and non-profit organizations. With the premiere of The Martian this week and as the day boots touch Martian soil draws closer, the supposedly trivial issue arises: which flag will flap in the Martian wind?

Will it be the banner of a country, similar to the planting of the U.S. flag on the moon? Or will it be the United Nations flag? Or the flag of a company like SpaceX? Or a new “Earth” flag designed for the purpose like this one?

Beyond the media politics of which flag is planted by the Mars equivalent of Neil Armstrong; there is the substantive issue of how Mars will be governed.

Initially when there are just a few astronauts, this won’t be an issue, just as it hasn’t been on the International Space Station. There are protocols that govern such teams and an exhaustive Space Station agreement for unusual cases. But eventually, enough people will arrive that governing, including implementing and enforcing criminal justice laws, will become a crucial responsibility of the settlers.

For ideas about how we can start a civilization on Mars, we can look to the ideas of science fiction and to our collective past. Unfortunately, many of the science fiction ideas seem practical only after settlements are there, not for the early colonization. Ultimately, history is probably a better guide. Human history provides a wealth of examples to learn from but I will focus on just four that I believe are relevant:

- City-States

- The Settling of the American West

- European Colonialism

- Internet Governance

The Incentives

Firstly and most importantly, we need to encourage expansion and development.

At the dawn of the space age, nations prevented a repeat of European colonialism with the Outer Space Treaty of 1967. The treaty prohibits any nation from claiming any celestial body in whole or in part. We should continue to guard against projecting our national divisions past the Earth.

The Outer Space Treaty of 1967 therefore precludes the principal driver behind European colonialism, grabs of territory and resources by nations. While this helps prevent the abuses of that imperialism, it also removes a powerful incentive.

Even without that treaty there would be no resource-based incentive for Mars. Unlike the relationship between the “New World” and “Old World” of European Colonialism, trade of physical resources will only go one direction – from Earth to Mars. There is no resource or product that we can currently conceive of that Mars might have or produce that would be economical to ship across the vast distance from Mars to Earth.

So what’s the incentive to go?

The incentives for individuals will be far ranging and reflect the same desire that drove previous human expansions – from a desire to be a part of something big to wanting to start anew. What’s missing is the incentive for organizations, from countries to companies.

An incentive for organizations is critical given that even the most lowball estimates believe it will take billions of dollars to build the infrastructure and put together each mission. That cost is far outside the price range of almost all individuals.

If Elon Musk is right about what his company, SpaceX, can do, companies will have the economic incentive. The key is for companies to be able to make a profit getting people to Mars at a price at least some can afford. Musk believes he can get the cost of an individual ticket down to $500,000. An admittedly huge number but one that enough people could afford to become the early settlers.

To provide the incentive for organizations to fund the actual colonies, a similar approach could be taken. In essence, each settler would pay a “settlement fee” to ensure the requisite infrastructure and materials are in place.

The way each person will fund each of these fees will vary, and that’s a good thing. Some will be able to pay out of pocket, possibly by selling all of their Earthly possessions and assets. Interested organizations, from religious groups to countries to various foundations, will sponsor others, similar to how a variety of organizations fund people to go to college.

The final component of the incentive structure is to ensure property rights and use. As noted, the Outer Space Treaty of 1967 prevents countries from owning any land but it leaves open the possibility of private organization ownership.

Allocating Land on Mars

To dispel any myths or ill-advised “land grabs” – the unscrupulous websites you may have seen that promise to sell people a plot on the moon or Mars are not the way to do this, and the commitments they’ve already made won’t be honored.

Rather, the way to do this is by combining the Internet and the settlement of the American West.

The Internet is a giant planet, in a sense. Each “plot of land” is what we call a domain name. For instance, Google owns the plot of land called “Google.com” Each of those land plots is ultimately issued by the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN), a non-governmental organization.

ICANN doesn’t own the Internet; it merely assigns plots of land so people don’t run into one another. A similar organization can control issuing Martian land plots.

To provide a template for the plots themselves, we can look to the settlement of the American West. The U.S. Government granted tracks of 160 acres to settlers in the 1800s through the Homestead Act. Settlers were required to be living on their plots so people couldn’t just grab up tons of land and they had to develop the land at least enough to live on.

A similar system should be used for Mars. Each plot will be a certain size, issued to a settlement as a whole and have a few requirements including residency and use within a certain time frame.

Governance

The second guiding principle is to encourage innovation and experimentation in societal and governmental structures.

Initially, each settlement on Mars should follow the laws and prohibitions of their sponsoring country or the country from which they launched if they are sponsored by an individual or non-governmental organization. This is due to practicality – when settlers first arrive, it will be a battle to create a surviving self-sustaining colony, and debating laws is not a great use of energy at first. Given the logistical challenges and technical lack of jurisdiction due to the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, such laws will be self-enforced, and there are likely to be modifications. This is expected and actually should happen. Additionally, the original laws should sunset.

Within a certain period of time, say no longer than 10 years, the original system of laws adopted from Earth should sunset and force the settlement to start from scratch. They will no doubt borrow from Earth-based examples and hopefully integrate their own trial ideas.

While some may claim that the perfect society or government structure already exists, that’s hubris. There are still improvements to be made and importing Earth-based societal structures to Mars may not make sense. Future Martians will face unique challenges including an environment more hostile than anything on Earth – including the forced close proximity of people and a lack of natural resources. The “best system” in the minds of some people on Earth may not be workable on Mars.

And perhaps more importantly, all of humanity benefits from witnessing diversity. Just as U.S. states and cities benefit from watching the successes and failures of their peers, so all of humanity would benefit from learning from trials on Mars. The early city-states around the world, especially in Greece, provided lessons we still take advantage of today such as the example of Athenian democracy. Some Martian city-states will choose to stay autonomous while others will join together, we will all learn from those trials as well.

To help facilitate Martian city-states learning each other’s lessons and to ensure there are conflict resolution mechanisms outside of a space war, there should be analogs of the United Nations and World Trade Organization. I recognize both those organizations are far from perfect but they are valuable concepts that facilitate coordination and peaceful conflict resolution without suppressing the innovation in governance we should seek to foster.

In response to my original question – What flag will fly on Mars? I hope the answer is a diverse set of flags and a whole lot of them.

This brief set of guiding principles and historical examples is not exhaustive, there are numerous other challenges to be worked out, and there are many places where this framework could fail, but hopefully it lays the scaffolding to minimize the risks and maximize the potential. To paraphrase Churchill, this is the worst possible framework, except for all the others.