What is Shared Parental Leave?

Shared Parental Leave (SPL) in the UK allows eligible parents to split maternity leave. Under the policy, birth mothers must take two weeks of maternity leave but can donate the remaining 50 weeks as SPL. Both parents can then share these 50 weeks, taking them simultaneously or in alternating blocks. The intention behind the policy is to better equalize parenting responsibilities. Yet, six years after its introduction in 2015, uptake is as little as two percent.[i] Why? The policy is inadequately funded, and therefore not a financially attractive option for most households; it is clumsy and complicated; and it has several unhelpful and stringent eligibility requirements. It also does not go far enough to undo deeply ingrained historical cultural norms surrounding gender roles. Not only do these norms hinder equity, they also impact and limit the experiences of the broader population: fathers lose out on time with their children, same sex couples are challenged with navigating a narrow system and people are increasingly expected to embody and promote equality yet are born into a system that is inherently unequal from the start. This article focuses primarily on heterosexual relationships—the impact of SPL on other family structures warrants additional study.

Why is (well designed) SPL good for gender equity?

- Role-modelling equity in the home

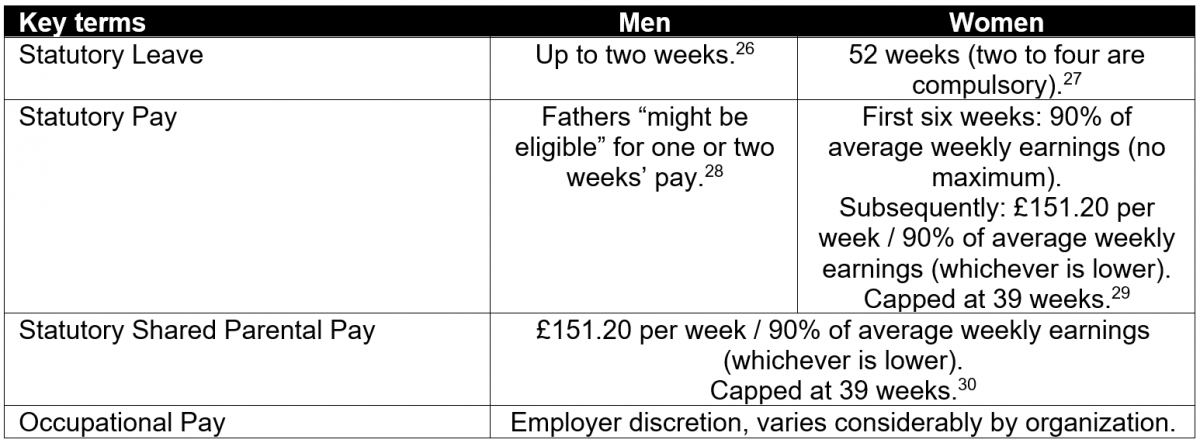

To understand SPL’s full impact, it is necessary to situate the policy within the wider context of UK parental leave. Without SPL, new mothers receive 52 weeks of Statutory Maternity Leave and 39 weeks of Statutory Maternity Pay (see Appendix 1). New fathers, on the other hand, receive a maximum of two weeks of Statutory Paternity Leave and Pay. Occupational Maternity and Paternity Pay overlay the statutory offering and vary considerably by organization, though the disparity in length for men and women is consistent with statutory leave. Not only is differing maternity and paternity leave incompatible with non-nuclear family structures, it firmly establishes women as carers and fathers as workers. This sets a visible precedent for traditional gender roles from the start of a child’s life.

SPL helps equalize the division of childcare across parents.[ii] Besides the act of breast-feeding, there are few parenting tasks that cannot be shared, yet only 31% of working parents purport to split childcare equally.[iii] Women, often heralded for their ‘mother’s instincts’, are given a head start in the current system as they spend more time with their infants. The three fathers interviewed for this article corroborated that SPL, which they took advantage of, helped to equalize family and household responsibilities. Moreover, the benefits of SPL extend far beyond a child’s first year. If men are more involved in the early years of childcare, they are more likely to stay involved as their children grow up.[iv] A Swedish father who took advantage of SPL corroborated that it “set the agenda for the next 10 to 20 years” both in terms of domestic labor division between him and his wife and his relationship with their children.

- Equalizing absence and opportunity in the workplace

In addition to equalizing the presence of parents in the home, SPL equalizes the absence of parents from the workplace. The status quo of UK fathers taking leave tantamount to a long vacation per child enables most men’s careers to continue largely uninterrupted. The same is not true for women. Time out of work limits career prospects: it directly hampers professional skill development and indirectly influences hiring, women’s employment status and equal representation in certain occupations. While there is a gender gap in time taken out of the workforce, it is unreasonable to expect equity within work.

Women are more likely to have a child than not and, if they do, mothers are granted more leave and greater benefits than their male counterparts.[v] As absences are highly costly for employers, this has significant implications for hiring and attrition and perpetuates gender bias, since men are regarded comparatively efficient hires. This ranges from inappropriate interview questions scoping out women’s likeliness to have children,[vi] to directly letting women go (an estimated 54,000 women per year lose their jobs due to pregnancy or maternity).[vii] The negative implications are clear for potential mothers—missed opportunities—but there are negative spillovers for everyone: women who have no intentions of having children are nonetheless penalized on the basis of their sex, and companies lose out on diverse talent. Bias is most keenly felt in small, resource-constrained organizations that struggle to cover absent employees—gender equity feels like an unaffordable luxury. Rather than unenforceable laws or positive discrimination to counter such bias, SPL addresses the root of the problem by spreading the absence and associated costs of parental leave across genders. This greatly diminishes the ‘motherhood penalty’ in favor of a more balanced ‘parenthood penalty’, thereby reducing employer discrimination.

Unproductive gender stereotypes in employment are pervasive. Male-dominated industries are often characterized as highly competitive and there is a real (or perceived) urgency to be ‘at the forefront’ in order to succeed. Roles where women tend to dominate are rarely characterized as such. In less ruthless environments, exit and re-entry and long absences are less of a hindrance (though nevertheless still challenging). One dad observed that even in Sweden—which is heralded as progressive when it comes to parenting—it was simply “not accepted” for friends with “highly competitive” jobs to spend six months at home. SPL cannot eradicate demanding jobs, but it equalizes career opportunities by normalizing periods of leave for all new parents.[viii]

By neutralizing the impact of having children across genders, SPL also establishes a foundation for economic equality. The UK suffers a persistent gender pay gap—British women earn on average 16% less than men per hour.[ix] Having children is one cause: the mean gender pay gap widens from approximately 8 percent before children are born to around 30 percent when the eldest child reaches age 20.[x] On average, during this period, mothers will have been in paid work for three years less than fathers, spent 10 fewer years in full-time work, and seven more years in part-time work.[xi] Women are currently over three times as likely to be employed part-time than men (40 percent compared to 13 percent of men).[xii] These differences in labor market experience contribute the majority of the pay gap that emerges after children, most notably the lack of wage progression in part-time work.[xiii] SPL helps to create a virtuous cycle: by equalizing the absence of parents at work, it advances pay parity, which in turn facilitates greater uptake of SPL. Fairer employment opportunities also perpetuates equity in later life—levelling the playing field in the type and amount of work that women do relative to men would help close the gender pension gap.[xiv]

- Equity helps everyone

When it comes to childcare, society benefits if we think of parents and not mothers first. The cultural associations of mothers as caregivers are strong and examples of sexism against male carers widespread. In the same way that women seek equality in spaces men previously dominated, mothers should make space for fathers in traditionally mother-centric spaces. The three dads interviewed have all observed maternal gatekeeping behavior: women who would insist on looking after their children alone, mothers reluctant to leave children alone with their fathers; women who deemed it their “right” to utilize their full maternity leave allowance; and women who “wouldn’t let” their partner take SPL. One dad was shocked at the unexpected behavior of some mothers he knew: “no matter how feminist they were before, [when they have children] the mother insists on a very classical set up.”

Fathers are increasingly expressing a desire to spend more time with their children.[xv] Unlike the current disparity in paternity and maternity leave which can leave one parent feeling excluded, SPL caters for “a new generation of fathers under 35 who want to do things differently”.[xvi] None of the dads interviewed were directly motivated by gender equity at a societal level but they agreed upon the immense personal gain—“I am a huge fan” championed one. They all spoke of the close bonds that they built with their newborn children and, overall, extremely highly of their leave. One father directly challenged the view that quality time can compensate for absence—“it really is quantity time that matters somehow.” Breaking down gender roles brings about broader benefits too. In the same way that household responsibilities need not fall to one gender, the burden of ‘breadwinning’—a role traditionally assumed by the patriarch of the family—is also equalized. It could be beneficial to spread the burden of financial provision and the accompanying pressure across both parents.

Attitudes towards gendered roles in parenting cannot be changed overnight, or with policy alone. Nevertheless, policy is a tool that can facilitate cultural change and advancement towards parity. In Sweden, where SPL has existed since 1974, ‘latte dads’ are not considered exceptional and shared parenting is more accepted.[xvii]

How can we make SPL more effective?

“I consider England as progressive in most parts compared to Sweden, but when it comes to this, it is quite shocking . . . a lot can be done”

~ A Swedish father who took SPL

With less than two percent uptake in the UK, SPL does not deliver the benefits outlined above. Three main areas require improvement.

- Increase pay and incentives

Inadequate pay is the primary reason behind the low uptake of SPL in the UK.[xviii] For reference, statutory pay equates to an annual income of approximately £8,000 a year, less than half a UK living wage.[xix] Where fathers earn more than mothers (as most do), and fathers are not eligible for enhanced occupational SPL benefits, it does not make financial sense, in the short term, to utilize statutory pay instead of company-enhanced maternity leave benefits. Even progressive parents who intend to share parenting responsibilities utilize alternatives to SPL.[xx] It is unrealistic to expect households to significantly reduce their incomes. To make SPL an attractive option, it must therefore be resourced with appropriate wage levels. For example Swedish parents receive 80% of their normal salary.[xxi] Going a step further, SPL could be positively incentivized, as in Germany where parents receive two extra months for opting in.

The challenge lies in how to fund SPL. The levers available sit with government and employers: maternity, paternity and shared statutory leave and pay, and occupational leave and pay. Various stakeholders advocate different solutions: Working Families, for instance, champions lengthened paternity leave, no reduction to the existing provision for mothers, and a continuation of SPL with a portion of transferable maternity leave—“it shouldn’t be a zero-sum game.”[xxii] However, this option and another advocated solution, raising statutory Shared Parental Pay, are tough sells to resource-constrained employers.

A more realistic alternative is to redistribute the current occupational maternity budget to parents—regardless of gender—since most employers already provide occupational maternity benefits as part of company policy. The UK could mandate that any supplement beyond the state contribution must be granted equally to women and men. This solution is particularly compelling as it can be executed at no extra cost if company maternity provision is redistributed rather than added to. Some UK organizations are role-modelling SPL occupational pay in accordance with occupational maternity pay; however, this falls short until all organizations in the UK enhance SPL benefits.[xxiii] Rather than companies budgeting for costly absences by women who have children, that same cost could be spread across all employees, regardless of gender.

- Expand eligibility and improve execution

Eligibility for SPL could be widened: agency workers, contract workers and self-employed people are not currently eligible. There are also constraints around notice periods, minimum earnings and tenure—a likely increasingly significant hurdle during the pandemic, especially for women.[xxiv] Despite being an extremely simple concept, SPL is not simple in practice. There are several variable inputs (both parents’ incomes, both parents’ occupational benefits) that make it difficult to sketch out broadly applicable general scenarios. Working out the specifics is therefore left to each family. The fathers’ accounts of the process of taking SPL in Sweden and the UK were vastly different. In Sweden, “the system, at least for me, made it very easy to split it . . . it is not complicated”. The UK dad, on the other hand, told a different story. He spent a large amount of time studying the policy and engaging back and forth with HR: “it is quite a lot of hassle and a lot of forms to fill in . . . it could be quite daunting if HR was not supportive or not used to administering it.” Coordination between parents’ employers is required and cajoling may be necessary. If the government wishes to encourage the uptake of SPL, it needs to expand eligibility, lessen the burden on new parents to understand and enact the process and raise national awareness of the policy, clearly communicating its benefits.

- Rethink the system

SPL marks progress for gender equity but it is not effectively changing the behavior of UK parents. This has a lot to do with the unequal legacy system. To start, it would help to redefine what society considers good. Currently, ‘good’ maternity leave is based upon length and amount of pay. The downsides of skill stagnation and reduced earning potential are largely invisible, hard to measure and much less frequently discussed, for instance relative to occupational maternity benefits. They are therefore rarely factored into childcare decisions. ‘Best in class’ maternity policies, whose benefits exceed those offered by SPL can hinder its uptake.

Furthermore, bias is built into the policy as it requires mothers to give up their maternity leave to transfer any part of it as SPL. This counters the apparent intent of the policy to equalize childcare responsibilities across parents, as it presumes the mother to be the primary carer in the first instance, adding weight to existing cultural hurdles. Behavioral economics would also suggest this element hampers the policy’s effectiveness as people are loss averse. Apportioning parental leave equally from the start (aside from the period surrounding birth) would establish a powerful default. In practice, the UK should adopt the ‘use it or lose it’ component that features in other countries’ better performing parental leave policies. For reference, 90% of dads in Sweden take at least some portion of SPL.[xxv]

Furthermore, while SPL exists alongside the legacy system of distinct maternity and paternity leave, its chances of success are limited. In its current form, SPL feels like a sticking plaster solution to address a problem of inequity that permeates a much larger system. As society has evolved away from the traditional gendered family model, parental leave policy has been amended and SPL added. What is needed however, is a complete and comprehensive overhaul of the current provision to meet today’s needs. If SPL included everyone and was financed effectively and consistently for men and women, separate maternity and paternity policies would become redundant and SPL could be the default and only policy required.

Final thoughts

Overall, while childcare decisions for each family may make sense within the constraints of current parental leave policy, these constraints exacerbate pervasive gender roles: vastly different lengths of parental leave mean women are seen as mothers before workers and men as workers before fathers. The effect of these roles permeates far beyond childcare and creates inequity in broader domestic responsibilities, employment opportunities and ultimately wealth in old age. The UK’s current SPL policy, with its devastatingly low uptake, is doing little to counter these deeply entrenched norms. That said, while it is easy to criticize the nascent policy, it is undoubtedly a step in the right direction and time is needed to achieve significant change. The embryonic policy is also subject to review—there is hope that an upcoming impact assessment will provide greater clarity on its adoption and result in implementation improvements.

To encourage uptake and ultimately realize the benefits of SPL, this article recommends the following changes: at a minimum, the financial barriers to taking SPL need to be removed. This can be done cost-effectively by reallocating employers’ existing maternity provision equally across genders. In addition, eligibility for SPL needs to be expanded to include more families. Furthermore, policy can be implemented in a way that increases its effectiveness as a mechanism for change; to further encourage adoption, SPL should be made the default policy and ‘use it or lose it’ built-in to encourage fathers to utilize their portion of leave. With these changes, SPL becomes a compelling and inexpensive solution to eradicate gender roles and advance progress towards gender parity. SPL is a particularly efficacious tool as it addresses a watershed moment in parents’ lives where, for most men and women, their experiences diverge significantly and inequality emerges. I remain deeply optimistic about the power of SPL as a solution for gender equity and am excited for it to evolve in the coming years.

Appendix 1

Endnotes

[i] Elizabeth Howlett, “SPL Uptake Still ‘Exceptionally Low’, Research Finds,” People Management, 7 September 2020, accessed 21 January 2021, https://www.peoplemanagement.co.uk/news/articles/shared-parental-leave-uptake-still-exceptionally-low.

[ii] Modern Families Index 2020 Full Report (London, Working Families, 2020), 12 [PDF file].

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] Mubeen Bhutta, former Head of Policy and Influencing, Working Families, conversation with the author, 15 December 2020.

[v] 81% of women who reached age 45 years in 2018 had at least one child.

“Childbearing For Women Born In Different Years, England and Wales: 2018,” accessed 16 January 2021,

[vi] Mubeen Bhutta.

[vii] “Plans To Boost Protections For Pregnant Women and New Parents Returning To Work,” UK Government press release, accessed 16 January 2021, https://www.gov.uk/government/news/plans-to-boost-protections-for-pregnant-women-and-new-parents-returning-to-work.

[viii] Madelaine Gnewski, “Sweden’s Parental Leave May Be Generous, But It’s Tying Women To the Home”, The Guardian, 10 July 2019, accessed 17 January 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/jul/10/sweden-parental-leave-corporate-pressure-men-work.

[ix] “Gender Pay Gap In the UK: 2020,” Office for National Statistics, last modified 3 November 2020, accessed 17 January 2021, https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/earningsandworkinghours/bulletins/genderpaygapintheuk/2020.

[x] Monica Costa Dias, Robert Joyce and Francesca Parodi, Wage Progression and the Gender Wage Gap: The Causal Impact of Hours of Work (The Institute for Fiscal Studies, 2018), 19, [PDF file].

[xi] Ibid., 13.

[xii] Brigid Francis Devine and Niamh Foley, Women and the Economy (House of Commons Library, 2020), 4 [PDF file].

[xiii] Dias, Joyce and Parodi, Wage Progression, 19.

[xiv] “Wide Gap In Pension Benefits Between Men and Women”, OECD, accessed 17 January 2021, https://www.oecd.org/gender/data/wide-gap-in-pension-benefits-between-men-and-women.htm.

[xv] Modern Families Index, 13.

[xvi] Mubeen Bhutta.

[xvii] Libby Kane, “Sweden is Apparently Full Of ‘Latte Dads’ Carrying Toddlers—And It’s a Sign of Critical Social Change”, Business Insider, 4 April 2018, accessed 17 January 2021, https://www.businessinsider.com/sweden-maternity-leave-paternity-leave-policies-latte-dads-2018-4?r=US&IR=T.

[xviii] Mubeen Bhutta. Anecdotal evidence supports Bhutta’s assertion—one father observed a direct correlation among peers between the uptake of SPL and where it was financially incentivized. Furthermore, none of the three fathers interviewed were financially penalized for taking SPL. Where it made financial sense, one dad stated it would be “quite silly not to take it”.

[xix] Assumes statutory pay for 52 weeks in a year. Annualized living wage calculation assumes £9.50 per hour working seven hours a day for 250 working days.

Living Wage home page, accessed 17 January 2021, https://www.livingwage.org.uk/.

[xx] For example my sister and brother-in-law who unwittingly galvanized the writing of this article—they will maximize a ‘generous’ maternity benefit and utilize unpaid leave to achieve shared parenting.

[xxi] Libby Kane, “Sweden is Apparently Full Of ‘Latte Dads’”.

[xxii] Mubeen Bhutta.

[xxiii] For example, the Civil Service, the Bank of England, several UK universities and a handful of finance sector companies.

Frances O’Grady, TUC Equality Audit 2016 (London, TUC, 2016), 31, [PDF file].

[xxiv] Anu Madgavkar et al., “COVID-19 and Gender Equality: Countering the Regressive Effects”, McKinsey Global Institute, 15 July 2020 https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/future-of-work/covid-19-and-gender-equality-countering-the-regressive-effects.

[xxv] Helen Norman and Colette Fagan, “SPL In the UK: Is It Working? Lessons From Other Countries,” Working Families, 5 April 2017, accessed 21 January 2021, https://workingfamilies.org.uk/workflex-blog/shared-parental-leave-in-the-uk-is-it-working-lessons-from-other-countries/.