BY ANGELICA QUICKSEY

“Explore. Experiment. Evaluate. Be delightful!”

These words, beside a dry-erase drawing of a double-sided funnel, are scrawled across one of many whiteboard-coated walls in an office full of sticky notes, markers, and a quiet buzz of activity. The office sits on the fifth floor of Boston city hall and hosts a small group of designers, researchers, and technologists. This group is charged with experimenting on the public’s behalf under the banner of the Mayor’s Office of New Urban Mechanics (MONUM).

Since 2010, MONUM has piloted and scaled projects across Boston in education, housing, public works, and more. The team is small, but their outsized impact demonstrates the power of design at work. Whether at the local, state, or federal level, government teams can look to MONUM for inspiration on applying a human-centered design framework to policy challenges large and small.

MONUM’s work demonstrates that design is more than a visual discipline. In the last decade, it has emerged as a set of problem-solving tools driven by specific mindsets.

While MONUM’s approach is rare in government, design thinking or human-centered design is becoming more common in the private sector. With roots in the world of industrial design, companies like the design-consulting firms IDEO and frog initially popularized and spread these methods.[1] They helped other firms create tangible products through an iterative process, using empathy to understand user needs and prototypes to test their assumptions. As the discipline matured, many companies began using similar approaches to design strategies and experiences beyond physical products.

In the policy world, design offers a framework for improving service delivery at various levels of government. As one of the most sophisticated public sector design teams, the New Urban Mechanics’s approach offers lessons for policy makers at all levels in the mindsets and methods of design.

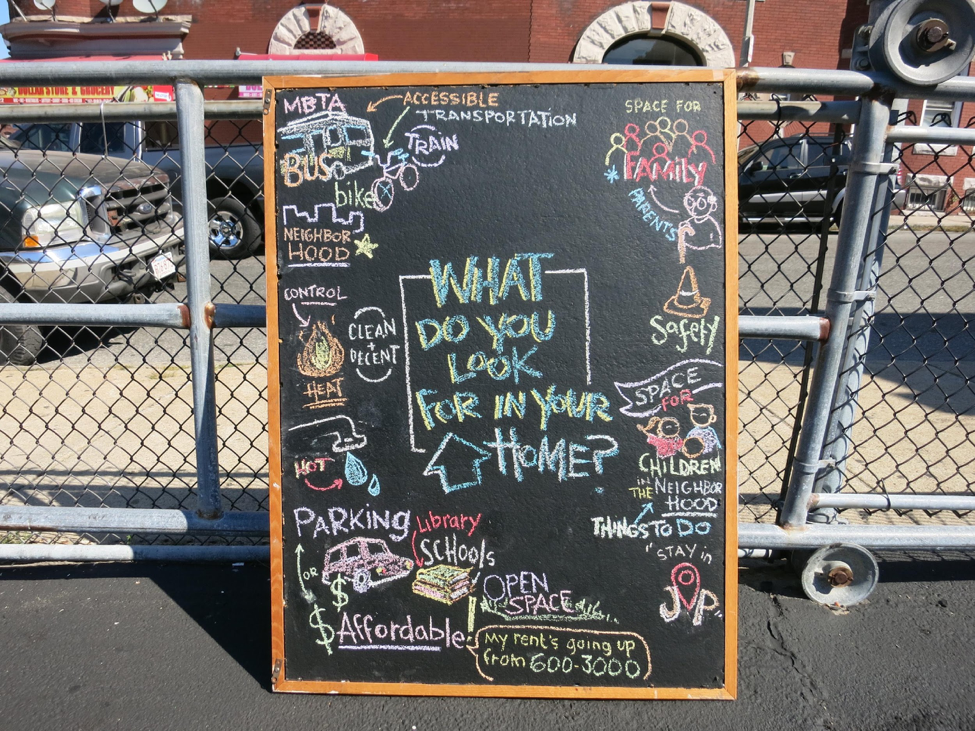

Explore: Engaging with Residents

In early 2016, MONUM was tasked with finding creative options for affordable middle-income housing in Boston. The Housing Innovation Lab team members—MONUM divides its work between several thematic “labs”—quickly found themselves swimming in data. To begin tackling housing affordability, the lab partnered with the Department of Neighborhood Development (DND), which had crunched the demographic and financial numbers, searching for gaps and opportunities. While helpful, the data didn’t say anything about residents’ experience in the city.[2] To supplement DND’s insights, the MONUM team constructed a traveling chalkboard bearing the question “What do you look for in a home?” They began visiting Boston neighborhoods, having brief conversations with residents who contributed to their chalkboard. As follow up, MONUM’s team members conducted hour-long interviews with a dozen of the people they’d met in the neighborhoods to gain deeper insights.[3]

SOURCE: Mayor’s Office of New Urban Mechanics

SOURCE: Mayor’s Office of New Urban Mechanics

By starting with users—in this case residents seeking to live in the city—and engaging directly with them to understand their needs, MONUM demonstrated a key component of user-centered design. In this approach, designers begin by collecting information, listening, and, importantly, observing the people affected by their intervention. Because people’s actions can contradict their stated preferences, designers go deeper than surveys and focus groups through ethnographic research to target behavior. By combining deep qualitative research with quantitative insights, designers are better equipped to translate data into priorities.

Designers refer to this process as building empathy, and, indeed, the insights that emerge are usually expressed in more emotional terms than traditional value propositions. Design-centric organizations use the emotional value proposition to address how a business decision or market trajectory will positively influence users’ experiences, according to designer Jon Kolko.[4] Creating a great experience becomes the goal of every customer-facing function and offers an opportunity to build in a human touch.

Government agencies have employed this kind of research outside of Boston as well. In Copenhagen, the MindLab, another public-sector innovation unit, applied this approach to Denmark’s tax system.[5] Working with the Danish Tax and Customs Administration (SKAT) in 2010, the MindLab team conducted intensive one-on-one interviews with staff at the SKAT department and local call centers, as well as nine young people from three Danish cities.[6] They discovered that Danish young adults had trouble both understanding their tax obligations and using SKAT’s online payment system because of confusing and bureaucratic language. After hearing recordings of users engaging with their system, SKAT used MindLab’s research to improve its self-service site with more accessible language. They then collaborated with banks, financial institutions, and employers to help young taxpayers avoid penalties for underpayment.[7] By teaming up with government agencies and conducting qualitative, ethnographic research, agencies like MindLab and MONUM can tailor the services government provides to user needs.

Experiment, Evaluate, Iterate: Testing Assumptions with Real Interventions

From insights come prototypes. Whether MONUM is exploring a new streetscape to protect cyclists, an app to track school buses, or a novel incentive program for housing, the team embraces an experiment-driven policy practice. Prototypes might be digital or physical, images or diagrams. In one example below, the MONUM team used a full mock-up of a small apartment to test their ideas. For non-physical programs or processes like the application process for a marriage certificate, journey maps or storyboards[8] are often developed, and even role-playing is used. Using visual elements helps make otherwise intangible ideas tangible. In every instance, the purpose of the prototype is to evaluate how proposed solutions might fair in the real world. In this way, small-scale prototypes made of low-cost materials allow the team to test their assumptions before committing to larger programs and make it easier to rebound from failure.

Sometimes these prototypes lead directly to policy interventions. In a 2013 pilot project, the New Urban Mechanics partnered with the Public Works Department to tackle cyclist safety in Boston.

Since 2011, seven cyclists have died as the result of a collision with a large truck.[9] New Urban Mechanics team member Jaclyn Youngblood explained, “There’s a gap between the wheel wells on the trucks, and people would slide under that and get run over. So [we asked] how do we make that a safer interaction between the driver and the cyclist?”[10] Inspired by an effort in the United Kingdom, the team hypothesized that they could reduce the likelihood of cyclist fatalities by blocking the undercarriage of large trucks.[11] Over the next year, the team tested three different side guards on sixteen large vehicles. Initially made of PVC pipe, newer versions of the side guards became progressively more sophisticated. When a cyclist collided with a truck in 2014, they were injured but survived the crash.[12] “The prototype helped us determine how to best serve the biker while also considering the ease of use for the department,” elaborated MONUM Chief of Staff Susan Nguyen.[13] Based on research conducted by the MONUM team, Boston City Council passed a Truck Side Guard Ordinance in 2014 requiring large city-contracted vehicles be equipped with side guards.[14] The department continues to advocate for changes across the state.[15]

Within the MONUM Housing Innovation Lab, prototypes can bring abstract concepts to life. In summer 2016, the lab explored the desirability of micro-units—apartments of 385 square feet compared to the average 818 square feet across the east coast[16]—in Boston. As housing prices rise in the city, MONUM hypothesized that smaller units that cost less to build and lease could ease the housing crunch for middle-income residents. Yet it can be hard to imagine what living in 385 square feet feels like. For Housing Lab teammate Max Stearns “that’s how the Urban Housing Unit (uhü) came about. You can’t just say a square footage or talk about unit distribution. That doesn’t click. You have to show people.”[17] To give people the opportunity to experience an apartment on that scale, the Boston Society of Architects created the uhü as a full-scale prototype of a micro-apartment. MONUM took the uhü on tour across seven neighborhoods in the city, from Mattapan to East Boston. In July, Stearns, who studied law before joining the New Urban Mechanics, guided the large uhü trailer slowly onto the plaza outside city hall. Visitors mingled in the living room and explored the compact kitchen. “We discovered that the uhü had to be flexible; it had to accommodate different uses. But we also learned that people felt at home there,” Stearns explained of the unit.[18] As a result of the positive response, the city has recently called for teams of architects and developers to submit micro-unit apartment development proposals for a city-owned parcel of land in Roxbury, a central Boston neighborhood.[19]

SOURCE: Mayor’s Office of New Urban Mechanics

While side guards and miniature apartments are relatively sophisticated prototypes, many other prototypes are realized in paper or foam core. Cheap and easily modified materials allow designers or policy makers to quickly iterate on their ideas. In this way, an idea that fails can be tossed out, the materials recycled, and the lessons from it applied in a new direction. Prototypes are a low-risk way to innovate.

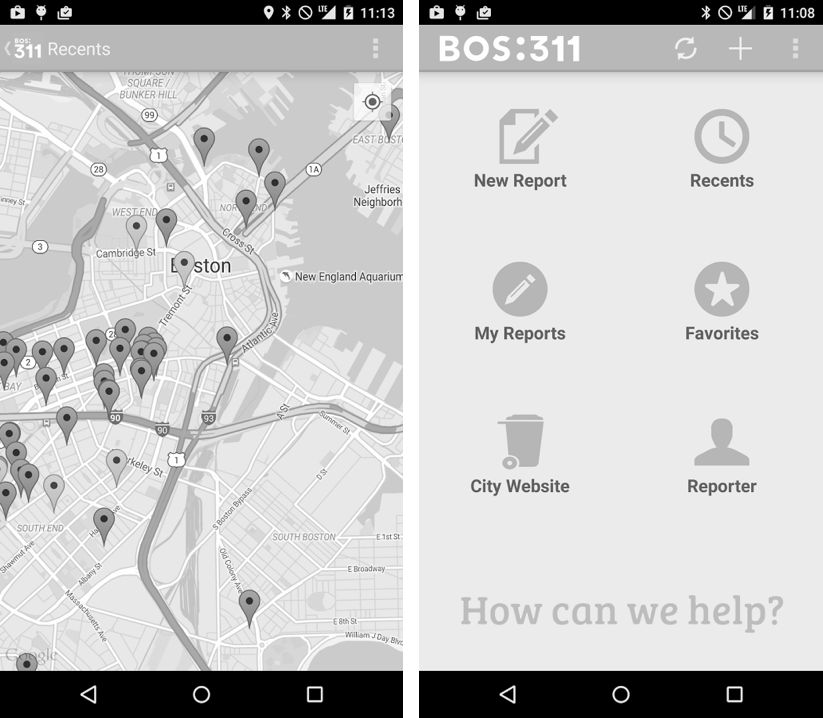

Iteration doesn’t stop with a product launch. The New Urban Mechanics earliest project, Bos: 311, has gone through several iterations.[20] Initially created in 2009 as an app called Citizens Connect, MONUM used the program to collect reports of problems from Boston residents—from graffiti to potholes.[21] Though these kinds of apps are common now, in 2009 the idea was novel. After discovering that the majority of reports were coming from a city hall employee, the team created a spin-off for internal staff.[22] Now rebranded and redesigned, the app has been embedded in the Department of Innovation and Technology with a dedicated team.[23] They continue to add new features like images of resolved issues to improve the functionality and user experience. Through projects like Citizens Connect, the MONUM team members live up to their reputation as municipal tinkerers and demonstrate a capacity for embedding their iterative design approach throughout the city.

MONUM operates under the assumption that policy, like design, is never complete. Susan Nguyen, the unit’s Chief of Staff, suggested that “people often try to craft the perfect policy to prevent things from happening. We try to ask how we might promote the right things and assume that policy is always a working document.”[24] She uses the iPhone as an example, pointing out that the phone is updated every other year to adjust to consumer needs. Particularly with the kinds of civic problems the city faces, like housing a changing population, addressing poverty, or accelerating climate change, the environment is always adapting and policy makers must do the same. As the environment changes, policy and program interventions must adapt as well.

Creating Solutions across Systems

The New Urban Mechanics staff likes to point out that design and policy are not at odds. Gathered in city hall, one member, Steve Walter, said: “We’re tired of people creating a dichotomy between design and policy. Any time you build a human system, you’re designing. We’re just lucky because [our office] has this perch that allows us to see the whole picture. One of our main value adds is perspective.”[25]

Similar efforts in other cities cast design teams as conveners. In Mexico City, the Laboratorio para la Ciudad has taken on citizen engagement using similar principles.[26] Copenhagen’s MindLab has addressed taxation and education reform by solving problems jointly across agencies.[27] Each group is able to take a wider picture of the system and use their research to discover the touch points for each user.

These practices don’t require a radical shift in process, but they do ask for a new mindset: that of a learner over a planner, a willingness to embrace ambiguity and learn from failure, and of course, empathy and optimism. These mindsets are more important than the methods themselves, according to Hila Mehr, who works in IBM’s market insights group.

Deep empathy through observing, listening, and engaging directly with people, a willingness to create and test through prototypes, and a commitment to revisiting solutions are crucial elements of a design approach to policy. Designing for policy puts real people at the heart of its practice in order to serve user needs, and it avoids large-scale failures by scaling up incrementally and testing solutions along the way. It helps to make seemingly intangible processes appear concrete because though design can apply to gadgets and digital tools, it can go beyond technology to serve diverse needs for real people. Employing a design mindset, policy makers and civil servants can draw on these methods to develop creative solutions to deeply embedded challenges.

Photo Credit: Mayor’s Office of New Urban Mechanics

[1] Robert Fabricant, “The Rapidly Disappearing Business of Design,” Wired, 29 December 2014, https://www.wired.com/2014/12/disappearing-business-of-design/.

[2] Susan Nguyen, Interview by Angel Quicksey, Personal interview, 28 December 2016.

[3] Sabrina Dorsainvil, Interview by Angel Quicksey, Personal interview, 28 December 2016.

[4] Jon Kolko, “Design Thinking Comes of Age,” Harvard Business Review, September 2015, https://hbr.org/2015/09/design-thinking-comes-of-age.

[6] “Case Study: Away with the Red Tape,” Mindlab, last modified July 2014, accessed 16 February 2017, http://mind-lab.dk/en/case/vaek-med-boevlet-et-bedre-moede-med-den-offentlige-forvaltning/.

[7] “Case Study: Young People’s Use of the Tax System,” Sharing Experience Europe: Policy Innovation Design, last modified 2014, accessed 16 February 2017, http://www.seeplatform.eu/images/SEE%20Case%20study%20-%20Young%20people’s%20use%20of%20the%20tax%20system.pdf.

[8] Storyboards and journey maps are both ways of diagramming out each step in a specific experience of a customer or business (e.g. buying groceries) both before and after the introduction of your product or service

[9] Steve Annear, “Mayor Walsh Wants ‘Truck Side Guards’ on All Vehicles Contracted by the City,” Boston Magazine, 9 September 2014, http://www.bostonmagazine.com/news/blog/2014/09/09/truck-side-guards-boston-ordinance/.

[10] Jaclyn Youngblood, Interview by Angel Quicksey, Personal interview, 28 December 2016.

[11] Erin Talkington and Claire Healy, “Honey I Shrunk the Apartments: Average New Unit Size Declines 7% Since 2009.” 15 September 2016. RCLCO Real Estate Advisers. http://www.rclco.com/advisory-apt-unit-size.

[12] Annear, “Mayor Walsh Wants ‘Truck Side Guards.’”

[13] Nguyen, Personal interview.

[14] Mayor’s Press Office, Marty Walsh, “City Council Passes Truck Side Guard Ordinance,” 29 October 2014, http://www.cityofboston.gov/news/default.aspx?id=14853.

[15] Steve Annear, “After Cycling Deaths, a Plea for Truck Safety Guards,” The Boston Globe, 6 January 2016, https://www.bostonglobe.com/metro/2016/01/06/bike-advocates-headed-state-house-for-safety-hearing/eqaZPieLFQ4xnpKTWiJkqK/story.html.

[16] Talkington, “Honey I Shrunk the Apartments.”

[17] Max Stearns, Interview by Angel Quicksey, Personal interview, 19 January 2017.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Office of Neighborhood Development, “City Launches Housing Innovation Competition for Compact Living Units,” 4 November 2016, https://www.boston.gov/news/city-launches-housing-innovation-competition-compact-living-units.

[20] Steve Towns, “Boston’s New App Rewards Citizens for Reporting Problems,” Governing Magazine, October 2013, http://www.governing.com/columns/tech-talk/col-boston-app-reward-citizens.html.

[21] Nick Carney, “Citizens, Connected,” Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation: Data Smart City Solutions, 21 May 2013, http://datasmart.ash.harvard.edu/news/article/citizens-connected-245.

[22] Michael Farrell, “Boston Deploys Smartphone App for City Workers,” The Boston Globe, 15 February 2012, https://www.bostonglobe.com/business/technology/2012/02/15/boston-deploys-smartphone-app-for-city-workers/rUAJE78YlmIs2W6HIqXiQN/story.html.

[23] Office of the Mayor, Martin Walsh, “Mayor Walsh Launches Boston 311,” 11 August 2015, http://www.cityofboston.gov/news/default.aspx?id=20283.

[24] Nguyen, Personal interview.

[25] Stephen Walter, Interview by Angel Quicksey, Personal interview, 19 January 2017.

[26] “Experimentos,” Laboratorio Para La Ciudad, accessed 26 February 2017, http://labcd.mx/category/experimentos/.

[27] “No Red Tape: Young Taxpayers,” MindLab, accessed 26 February 2017, http://mind-lab.dk/en/case/vaek-med-boevlet-for-unge-skatteydere/.