BY ALEXANDRA SCHMITT

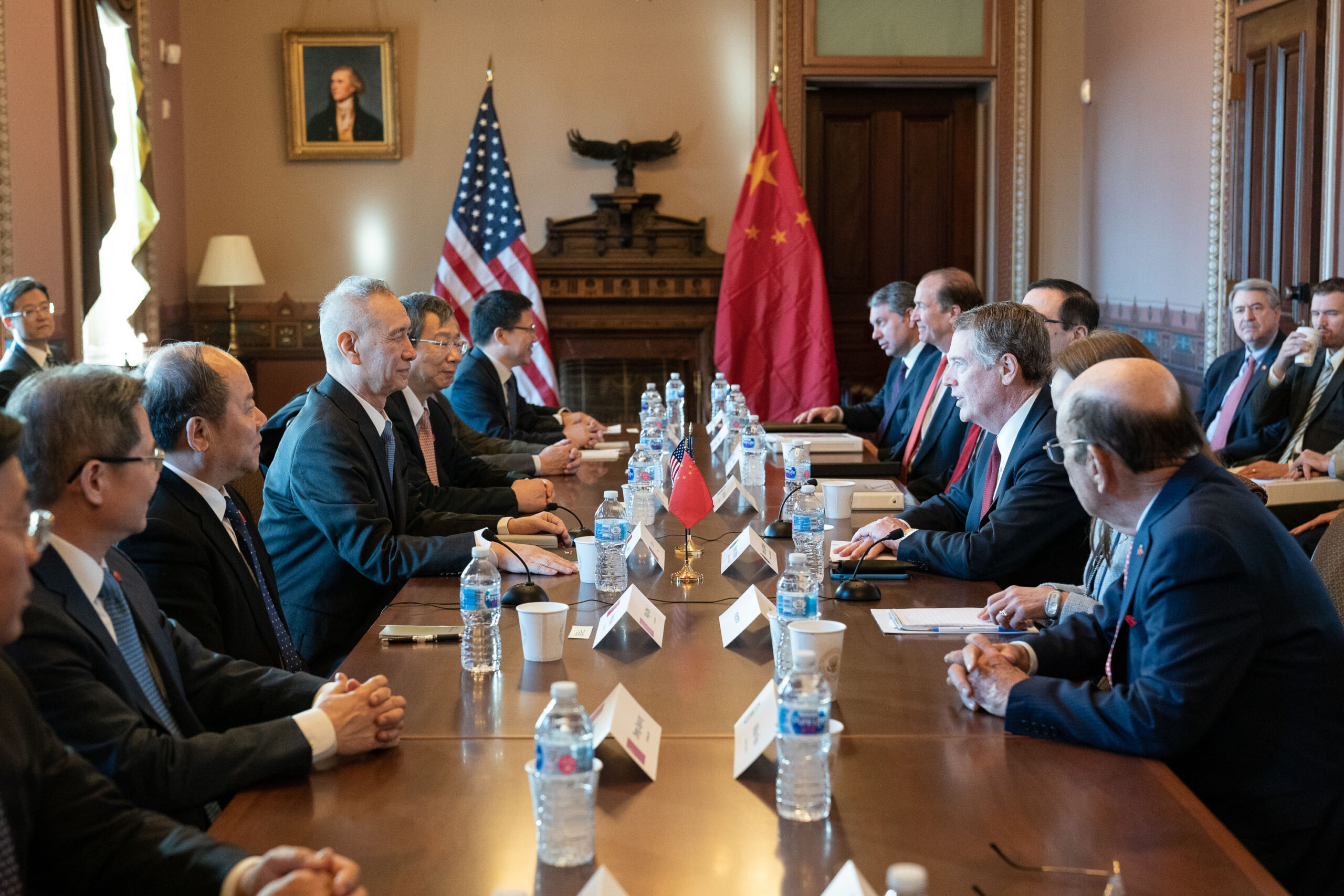

It’s a familiar photo in foreign affairs: a table in an ornate room, placards lined up, and a long row of men facing off on each side. One could be forgiven for thinking this was a throwback to the 1970s, when women were barred from serving as foreign service officers after marriage. Sadly, it’s the face of negotiations under the Trump administration, where women are often missing at the table.

If a picture says 1,000 words, Trump’s photo ops speak volumes about the role of women in this administration. The U.S.-China trade talks feature an impressive lineup of 17 male negotiators. Only two women made it to the table in February, where they served as translators. The most recent delegation announced by the U.S. Trade Representative features six white men. In a meeting at the White House between American and Saudi officials, the only women visible were journalists crowded at the back. The Singapore summit between Trump and Kim Jong-un again featured just one woman, a translator. Trump’s NAFTA renegotiations, EU tariff delegation, and Afghanistan talks have all been led by men.

In sum, Trump’s primary negotiators can be described as pale, male, and stale. From trade talks to peace deals, the Trump administration is falling short on gender parity. As a result, these negotiated deals and agreements are leaving value on the table.

While it’s hard to track the full composition of delegations with publicly available information, the visible examples point to a disappointing record. Compared to the last administration, this backtracking is disappointing. Wendy Sherman led the U.S. delegation that successfully negotiated the Iran deal in 2014. Susan Schwab opened negotiations for the Trans-Pacific Partnership in 2009. Hillary Clinton and Samantha Power served as prominent diplomats in the Obama administration. Although Nikki Haley replaced Ambassador Power at the United Nations under Trump, she recently left the administration, leaving just five women serving in the cabinet today. Haley’s nominated replacement, Kelly Knight Craft, is a political donor with no real diplomatic experience except for a short stint as ambassador in Canada. The position is expected to be demoted from the cabinet level. Without Haley, the serious face of U.S. diplomacy is, once again, white and male.

Research doesn’t back up this male-centric approach. In general, studies prove that men and women are equally skilled as negotiators. At the same time, evidence suggests that having women present at the table affects the final deal. A 2016 study found that when pairs of men negotiate, they tend to compromise less and opt for extreme proposals only. But when women and men negotiate together, the pair tends to go for compromise solutions[i]. In complex diplomatic negotiations, finding creative, workable compromises is crucial to making progress. Other studies found that women are less likely to use deceptive tactics than men when negotiating[ii], another important factor in fraught diplomatic relationships. On a practical level, greater diversity can diminish the possibility of groupthink and encourage original solutions to inherently challenging problems. More racially diverse groups that acknowledge different experiences and backgrounds result in better morale and higher productivity. Furthermore, a huge body of research shows that peace deals are better when women are involved: agreements are 35 percent more likely to last more than 15 years and 64 percent less likely to fail. In diplomatic negotiations, then, relying on homogenous delegations is already starting from a position of weakness.

In negotiations, they say that if you’re not at the table, you’re on the menu. The lack of representation in Trump’s negotiations isn’t just cosmetic — it affects real policies and legislation concerning women’s rights and access to services. One of the Trump administration’s first actions was to put in place the most restrictive version of the Global Gag rule—a Republican policy that cuts access to U.S. foreign aid for NGOs that provide family planning services—ever imposed. A photo of the signing ceremony went viral, with Trump surrounded by six other white men. Trump’s version of the policy restricts access to over $8.8 billion in funds; under the Bush administration, it affected $575 million.

In Afghanistan, where the United States is conducting peace talks with the Taliban, women’s rights are a huge stumbling block. Between 2001 and 2016, the United States spent over $1.5 billion trying to improve the lives of women and girls in Afghanistan. Now that peace negotiations are in motion, denying women a seat at the table means these hard-won rights are at risk of slipping away. The Trump administration has refused to take a strong position on whether women’s participation is a prerequisite to the next phase of negotiations. It’s clear, then, that when women aren’t present in these talks, issues that are critical to women are not prioritized, including girls’ education, gender discrimination, or violence against women. On top of it all, for an image-obsessed president, the dearth of women in these photos sends a disappointing message to young women and girls about their potential role in U.S. politics and policy.

The good news is that it’s not too late to bring women into this administration and to the negotiating table. Trump should make a concerted effort to appoint women to lead prominent talks and join delegations moving forward. For those outside of the administration, gender parity must be a major priority. Candidates gearing up for the 2020 elections should ensure that senior positions are held by women. Candidates can pledge, for example, to appoint cabinets with 50 percent women, as Canada and the UN Secretary General have successfully done. Pursuing these initiatives will ensure not only that more women have a seat at the table, but also that negotiators reach better deals that create value for both women and men.

Alexandra Schmitt is a second year Master in Public Policy candidate at the Harvard Kennedy School concentrating in international and global affairs. Prior to HKS, she worked on US foreign policy advocacy at Human Rights Watch.

Edited by Nikhil Kumar

Official White House photo by Andrea Hanks

[i] Hristina Nikolova and Cait Lamberton, “Men and the Middle: Gender Differences in Dyadic Compromise Effects,” Journal of Consumer Research, October 2016.

[ii] Jessica A. Kennedy, Laura J. Kray, Gillian Ku, “A Social-Cognitive Approach to Understanding Gender Differences in Negotiator Ethics: The Role of Moral Identity,” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, January 2017.