BY HENRI BREBANT

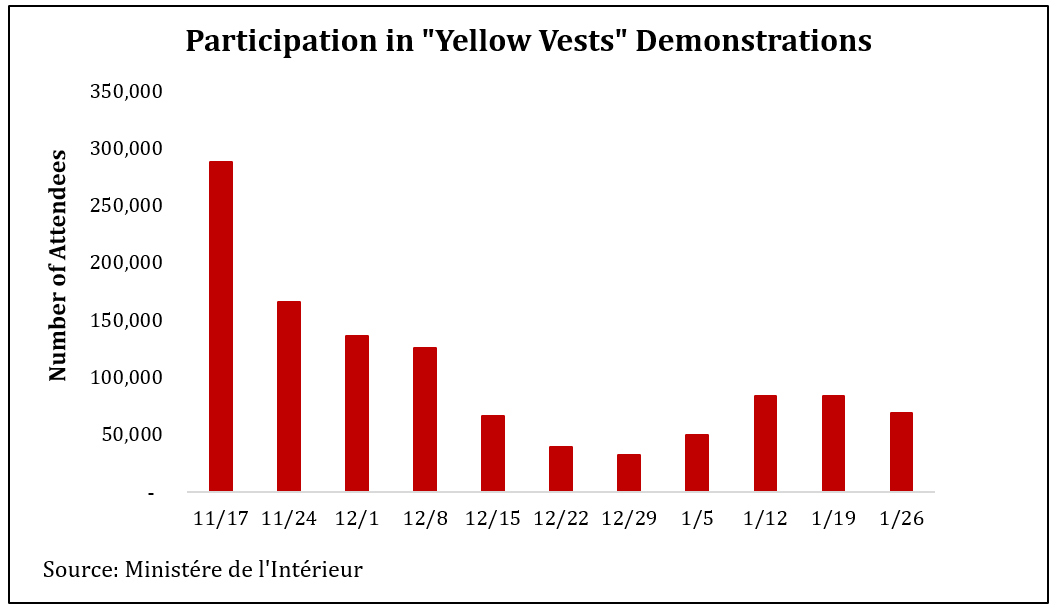

January 19th was the 10th consecutive Saturday that the “Yellow Vests” protested in France. The movement started in October 2018 with a viral video, a change.org petition and some Facebook events that pushed 290,000 people[i] into the streets and onto the roundabouts. Unstructured and distancing itself from political parties and unions, the movement denounced rising gas prices due to tax increases. Putting on yellow motorist vests to symbolize visibility, protesters claimed that high gas prices increased the economic insecurity of peri-urban and rural populations that commute by vehicle out of necessity, rather than by choice. They framed the debate as a question of economic justice and geographical inequality.

A month later, President Macron responded by undoing gas tax increases and raising the minimum wage. To partially meet Yellow Vests’ calls for a civic[ii] referendum, a “Grand National Debate” was launched to collect citizens’ ideas for reform and reduce tensions. In a shrewd move, Macron mailed a letter to all the French, inviting them to participate in debates that would be held in every town. The President mobilized mayors after a marathon roadshow from Normandy to Dordogne. So far, over 3,000 meetings are planned for the “Grand Debate,” due to run until mid-March.

And yet 84,000 people marched the streets for the tenth week, despite Macron’s measures, Christmas and the cold. France’s sympathy for “Yellow Vests” remained stable at 60%—unprecedented for a social movement in France.

….

For the Yellow Vests, lack of direction is allegedly part of the movement’s cultural DNA. By refusing hierarchy or a leader, Yellow Vests differentiate themselves from past structures of democracy and promote direct access to officials and institutions. Some protesters self-identify their actions with revolutionary movements that similarly lacked structure, such as the 1789 revolution, the Commune of 1848 or the May 1968 crisis. Meanwhile, those opposing the conflict draw more caricatural comparisons, invoking the “Poujadistes” of 1950s or the “Jacqueries” of the Middle Ages..[iv]

But it seems that the Yellow Vest conflict is one battle of a deeper cultural war. Their vehement criticism of the “elite” resembles a class struggle. “Pushed away from the middle class into a new world of vulnerability and insecurity,”[v] Yellow Vests feel isolated, abandoned and sometimes despised. They are not only fighting governments, banks and technocrats, but rather a broader upper-class that “largely prospered from neoliberal policies of the past 40 years.” Decades of gloomy employment prospects and the attrition of public services in rural and suburban areas reduced social mobility and accentuated social polarization. French geographer Christophe Guilluy argues that this has shrunk the middle class and created the conditions for cultural conflict.[vi]

As a result, the Yellow Vests coalesced against a common enemy: the “elites.” Award-winning journalist Florence Aubenas describes how Yellow Vests settled camps on the roundabouts where they shared meals, discussed ideas, and socialized. On the roundabouts, people found community and a way to reinvent themselves that contrasted with the materialistic happiness they struggled to afford. On the Facebook groups, communities found a sense of nation-building, developing their own media outside of traditional press and TV. But the Yellow Vests sometimes risked getting locked into toxic echo chambers—a think tank memo explained that the average Yellow Vest’s Facebook newsfeed is 80% saturated by discussion of the movement. The result on Yellow Vest protesters is best summarized by Lucy, quoted in Le Monde Diplomatique[vii]: “Before I had the feeling I was alone….And look at how many friends I have now! I am 46 years old. I never read a book in my life. And since yesterday guess what I am doing at night, on the intersections?…I am reading the Constitution.”

The election of Macron catalyzed the cultural clash because his party projected an elitist image. 81% of his party’s supporters hold university degrees, as opposed to 64% among former Socialist Party militants and 28% as the national average.[viii] Let’s not forget that LREM largely benefited in the 2017 election from the fragmentation of populist candidates’ voters between the far-left and the far-right—voters that constituted 45% of the electorate. We should also not forget that many voters felt a sense of malaise and disillusionment at the ballot box.

And yet, the cultural explanation does not yield answers to the conflict. Sociologist Anne Dujin explains that the distinction between “the people” and “the elite” remains a simplistic dichotomy. Both labels are nebulous, do not capture the complexity of the underlying social dynamics, and make it impossible for politicians to reconcile a fractured society.

….

Above all, inequalities and social divisions in French society are not new, so why has social uproar exploded now? According to political scientist Barrington Moore, such a backlash occurs when the social contract is broken. In the case of the Yellow Vests, this has arguably manifested through the disempowerment of citizens and the recession of public services.[ix]

Is the government going in the right direction? The French government partly succeeded in pausing the conflict with the “Grand National Debate”—reducing the Saturday demonstrations to the most radical factions. However, it partly failed by focusing too much attention on Mr. Macron himself. If the movement carries on, will he hold steady against 84,000 people in the streets? Back in 2013, 15,000-30,000 so-called “Red Cap” protesters were enough to force the French Government to walk back a new tax on road freight transport—a move that cost the state around 1 billion euros.

So what can we do? Consistency and exemplarity should be promoted. All legislative projects impacted by the National Debate should be paused until the Debate ends. Above all, solving the crisis calls for national unity, similar to when France won the 2018 World Cup.

As philosopher Bruno Latour[iii] writes, “the ‘Yellow Vests’ foreshadow the battles of the future.” Battles where confusion and ambiguity will dominate. Going forward, let’s hope for France that decision-makers and citizens can be lucid and humble listeners.

Henri Brebant is a first-year Master in Public Administration Candidate at the Harvard Kennedy School. He previously worked for the French Government and for a global management consultancy. Co-chair of the European Club at HKS and engineer by training, he is passionate about European politics and the societal impact of new technologies.

Edited by: Hugh Verrier

Photo by: kriss_toff on Flickr

[i] By the numbers, it is an above average demonstration for France: half a million attended the demonstrations against labour law modifications in 2016, for example, and a similar number protested against the reform of public service in early 2018.

[ii] Yellow Vests want to facilitate the initiation of law-making referendums by citizens themselves (on the Swiss model), which requires changing the French Constitution.

[iii] Passer de la plainte à la doléance, Bruno Latour, Le Monde, January 9th 2019.

[iv] Historians agree that historical analogies are inadequate for explaining the conflict.

[v]Des gilets jaunes au New Deal Vert, Joseph E. Stiglitz, Les Echos, January 10th 2019, p.9.

[vi]No society: la fin de la classe moyenne occidentale, Christophe Guilluy, Flammarion, 2018, ISBN: 9782081422711.

[vii] “Avant j’avais l’impression d’être seule”, Pierre Souchon, Le Monde Diplomatique, January 2019, p.16.

[viii] La REM: Anatomie d’un mouvement, Terra Nova, 2018, p.5.

[ix] Injustice: The Social Base of Obedience and Revolt, Barrington Moore, London Macmillan, 1978—Quoted by Laurent Bonelli in Le Monde Diplomatique, January 2019.