BY SEAN KATES

The millennium could have started better for Americans. We saw the nation voluntarily enter two wars costly in terms both monetary and human. An ineffective government response exacerbated one environmental disaster, while private cupidity and stupidity caused another. Promises of universal home ownership crashed down around us, aided by slick financial creations misunderstood by everyone. At times, 10 percent of the nation stared unemployment in the face, and for the most part, it stared right back. War, environmental misdeeds, and economic hardship, the last decade has been a perfect breeding ground for protest music that would move the nation and set its hearts ablaze with a thirst for change.

Except none came

Instead, in a time of great social unrest, people looking for protest music had to go farther afield than at any other time in the past century. While there were a few commercially successful songs with social impact, popular music in the United States was dominated by boy bands, female solo artists, and an enchanting but innocuous dance-based hip-hop. Protest music played very little part in the largest social movements, even as musicians expressed their solidarity through other means. When the next generation makes a movie about this time in America (and it will), the film will lack a meaningful soundtrack.

Many will be inclined to ask, “So what?” But protest music has always played an important role in American society, especially in the cultivation of a social conscience. It serves two communicative purposes, one primary and one secondary. Overwhelmingly, protest music coordinates and strengthens a movement by appealing to the movement’s members. However, as a side benefit, it may also serve to persuade outsiders to join the fray.

We should care, then, why protest music has largely disappeared from our radio stations. There are many reasons for the decline that are endemic to the music industry itself, and we should strive to understand those first. After all, the landscape in which music is created and sold has certainly changed since the days of Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, Chuck D, and Johnny Rotten. However, as discussed below, these environmental differences cannot fully explain the recent draught of commercially successful but socially conscious music. We must look outside the industry and consider plausible reasons for this cultural phenomenon. Could it be that the new media so helpful in organizing the Tea Party and the Occupy movements has played a detrimental role, marginalizing its low-tech predecessor? If so, what future exists for this once widely prevalent form of political speech?

The Infantilizing Industry

Perhaps the most important difference between then and now is the audience. A shrinking industry has become ever more monopolistic, as independent labels are swallowed up into a limited number of multinational corporations, and radio stations both large and small fall under the ownership of Clear Channel or a select few other big fish. This consolidation and its resultant economic realities have altered the landscape in a new and unique way: audiences have become “target demographics” with a lowest common denominator fit for mass appeal. Such target demographics are likely to be very young and largely apolitical. In the view of the ever profit-maximizing corporation, newly pubescent minds are easier to shape and predict than an older audience and far more likely to support alternative revenue streams like television shows, movies, and country-wide tours. From the industry standpoint, political messages are best avoided, even when aimed at adults, since they unnecessarily split an already too narrow market.

The best-selling artists of the 1970s include Elton John, Peter Frampton, Neil Young, and Fleetwood Mac—all artists who appealed to a wide range of ages and politics. In contrast, the 2000s were dominated commercially by Taylor Swift, Justin Timberlake, Beyoncé, Usher, Eminem, and the enterprising youth behind the High School Musical soundtracks—artists with a far more narrow audience comprised mostly of the young. The trends, meanwhile, are moving ever younger and ever more “safe,” as Lady Gaga and Ke$ha leverage their vast armies of teenage fans to move up the list.

Meanwhile, the biggest stars with adult audiences are shying away from inserting politics into their music. One can understand such a reaction after the Dixie Chicks faced radio blacklists and ostracism from the country music community for speaking out against former President George W. Bush and the Iraq war. However, other claims ring more hollow. Chris Martin, otherwise politically active in the fair trade movement, explained that his band Coldplay—by some measures the largest rock band in the world—would not include these beliefs in its music because, in part, “It’s very hard to find things that rhyme with North American Free Trade Agreement.”[1] If only he had a slightly more elastic rhyming dictionary, it seems, he would be leading the modern protest music movement.

It should be noted that not everyone sat by quietly. Tom Morello, R.E.M., Ani DiFranco, and Michael Franti continued combining politics with song, though less profitably than before.[2] We discovered new voices in Lupe Fiasco and dead prez—hip-hop artists intent on filling the role previously occupied by socially conscious artists like Public Enemy and NWA. Green Day, of all bands, delivered a concept album and a Broadway musical focused on the dispiriting crush of being young and American, consumed with a fear and a fire you cannot acceptably express. But these are the outliers. Protest music, in general, is in steep decline.

Why it should be so is not altogether clear. Yes, popular music is aimed at a new audience, and yes, there are economic reasons to remove polarizing topics from one’s music. But these effects have not eliminated the large number of socially conscious adults looking for an outlet. Perhaps the decline in protest music was not solely determined by factors internal to the music industry after all.

The Twitter Bomb

Part of protest music’s power and appeal over the past half century was the breadth it offered to protest movements. In a locality-based world with few truly national or international media, communication (and thus, movements) tended to stop at borders, whether geographic or cultural. Commercially successful popular music could transcend those barriers and deliver a movement’s message from enclave to enclave, eventually uniting the pockets across the nation and, in some cases, the world. In music’s case, the medium mattered as much as the message in traversing the roadblocks placed by physical and social realities.

The advent of the Internet steamrolled those barriers. Technology flattened the world, globalization shrunk it, and protest music found nearly endless competitors. Individuals with general grievances could choose twenty-four-hour news channels that mirrored their views, while saving their specific gripes for partisan blogs that ensured that any political action would make at least one run through the snark gauntlet. Facebook and other social networking sites moved beyond facilitating snowball fights and extramarital affairs, launching platforms for like-minded protestors to join forces across the country. Using the new media, both the Tea Party and Occupy movements connected local groups to a national conversation and created platforms to facilitate the quick and efficient proliferation of their ideas. Twitter became the tool of choice for Americans following and supporting uprisings in the Arab world.

Meanwhile, traditional media is being forced to respond to the technological threat or wither in its wake. There are reasons to believe that this transition is harder for protest music than most others. From the writing process, to the time spent in studios, to the slow burn of a sung message transforming into a battle call as it finds its audience across the radio waves, protest music has always been a painstaking endeavor. And the world, in its current state, no longer seems to have time for it. One tweet can organize a boycott. An article about economic injustice can be linked to by hundreds, read by thousands, and misused by millions in less than a day. As news cycles shorten alongside attention spans, the process of creating protest music seems more and more archaic.

It does not help the cause of protest music that its own potential practitioners have taken up with the enemy, as musicians espouse their beliefs via the social networks most assured of bringing them attention and fame. They find ways to say in 140 characters what is apparently too difficult to artistically express in song. The echo chambers fashioned for us by modern technology have proven effective at giving us access to an endless amount of information we agree with while also ensuring that it is very hard for us to hear anything else.

The Future of Protest Music

If the above is true, and the communicative powers of protest music have been replicated and replaced by our new media, it would be far from the first time a new technology has made a form of communication obsolete. As a population, we have moved away from carrier pigeons, the Pony Express, telegraphs, and even the handheld landline, all in search of greater immediacy and convenience.

Still, there may be hope for the Pete Seeger stalwarts who are still among us. Protest music, unlike the media discussed above, has an emotional connection that, from time to time, can conquer the human drive for technological progress. As Wazir (Willie) Peacock, Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee member, noted in Seeger and Bob Reiser’s Everybody Says Freedom: “When you sing, you can reach deep into yourself and communicate some of what you’ve got to other people, and you get them to reach inside of themselves. You release your soul force, and they release theirs, until you can feel like you are part of one great soul.” No social networking site has yet managed to replicate this feeling—one that sits at the very heart of protest movements. Will this distinct advantage be enough to save the protest song? It’s an increasingly tenuous thread to cling to, but protest music fans have never had difficulty embracing lost causes.

[1] In other words, if it’s rhymes you’re afta’, don’t sing about NAFTA.

[2] For instance, R.E.M.’s aptly titled environmentalist album Green sold well over two million copies in the United States. Around the Sun, Accelerate, and Collapse into Now, the band’s three releases from this period, sold about a third of that—combined.

Sean Kates is a 2013 Master in Public Administration candidate at the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University. Prior to graduate school, he worked with local and state governments to increase their emergency management capabilities.

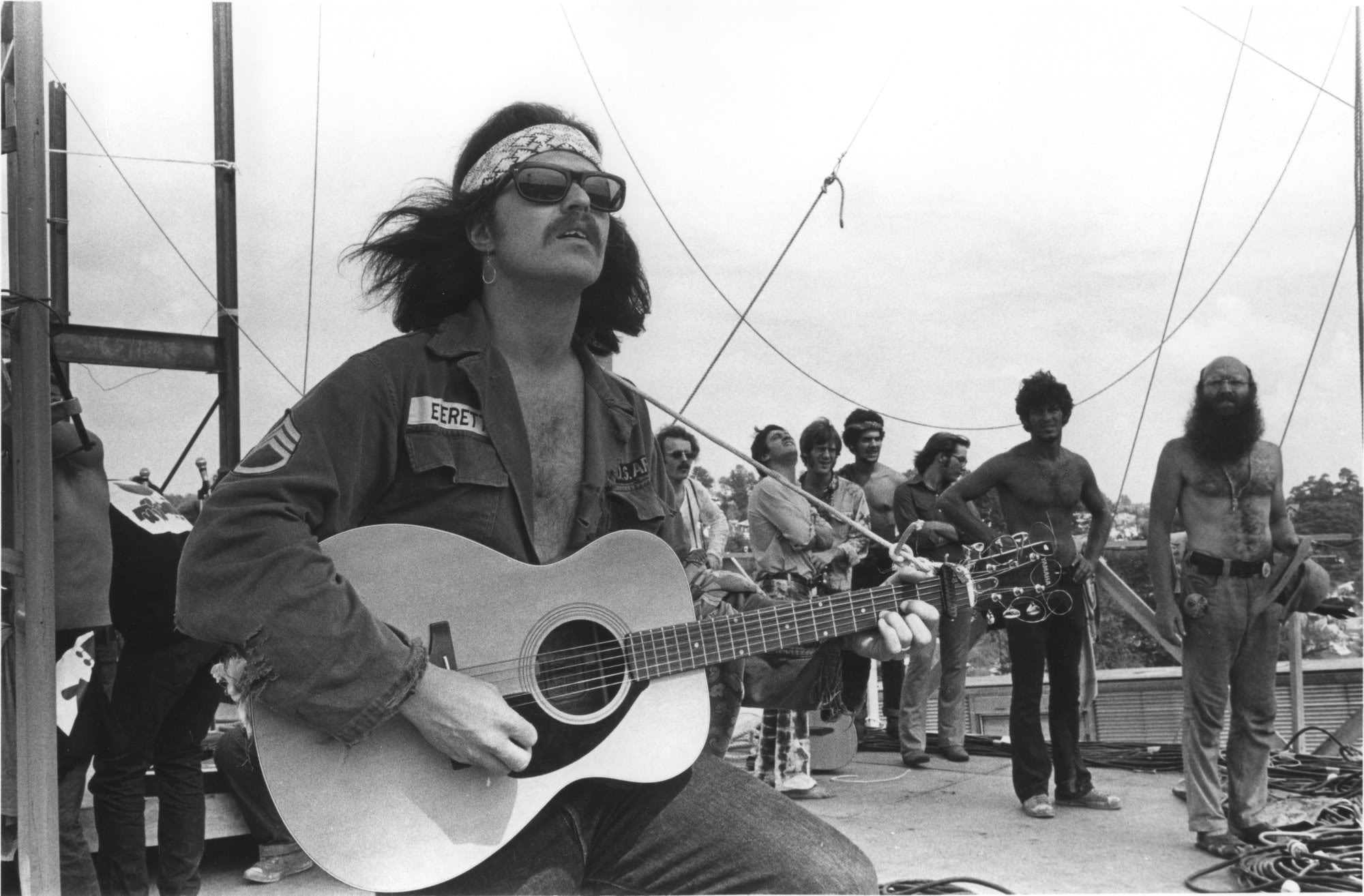

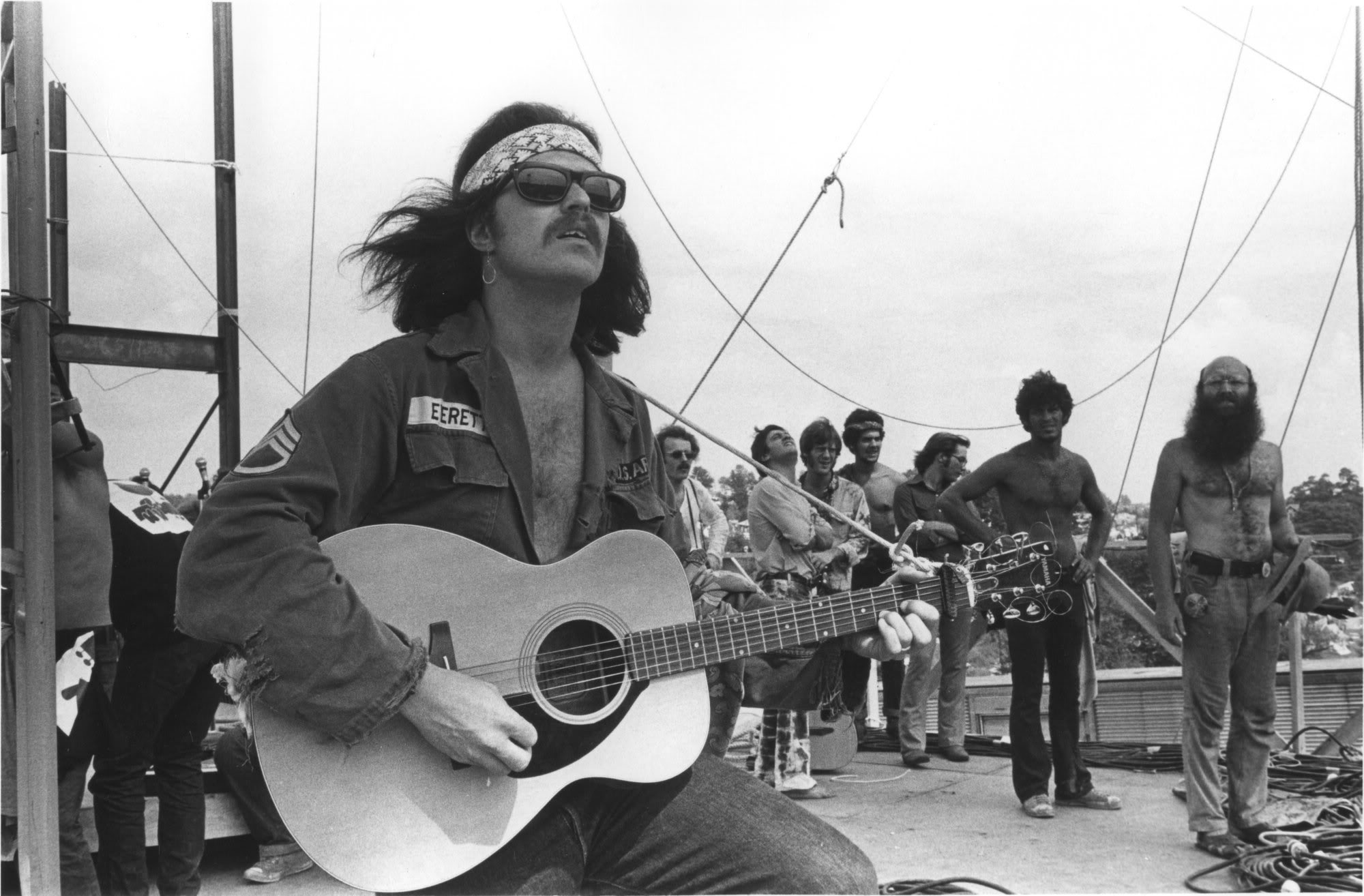

Photo source here.