This piece was published in the 33rd volume of the Asian American Policy Review. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

If my previous identity query was grounded on, and perhaps confined by, this dualistic tension between Korea and America, the idea of diaspora liberated me from a geographic grounding of identity. It was a membership not only in the Korean or Korean American community but also in these larger sojourner communities around the world who share, no matter how remote or accurate, collective memories of the homeland, heritage and history.

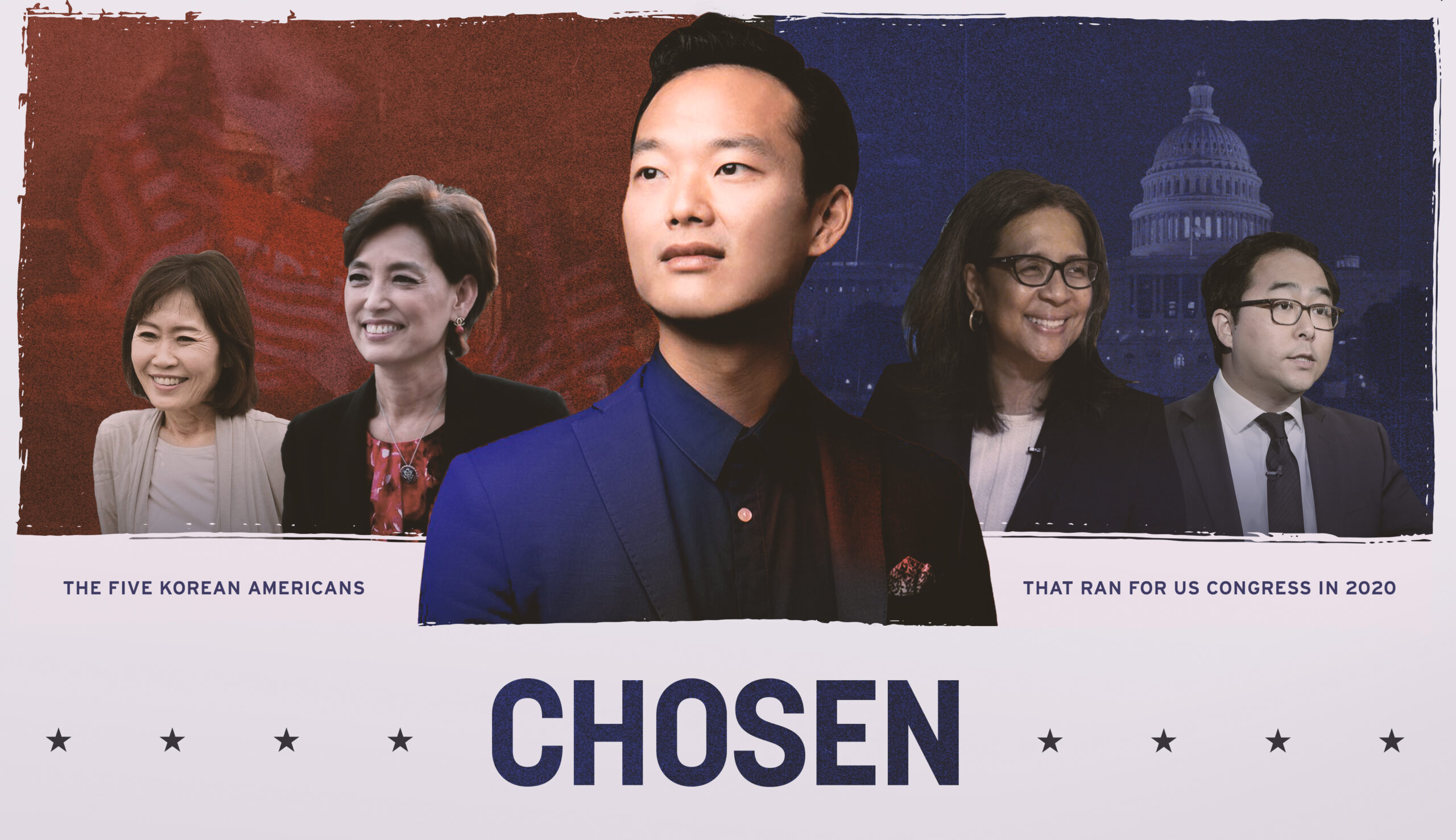

AAPR: Your latest documentary feature, CHOSEN, begins with a clip of “an old Korean man yelling about the importance of the 1992 LA riots in Korean American history.” In an interview with the Korea Herald,[i] you remarked that you wanted to start the film with that clip “because that’s the very moment where [your] life was changed” and you began to see the LA riots as “a turning point in which ethnic Koreans living in the US started to identify themselves as Korean Americans.” What do you see as other turning points in your life? Other turning points in Korean American society?

JUHN: The genesis of Korean immigration to the US began in 1903 when the first group of Koreans arrived in Hawaii to work at sugarcane plantations. While many, but certainly not all, descendants of the original settlers retained a sense of Korean identity, the vast majority of who we refer to as “Korean immigrants” arrived in the US after the passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965.[ii]

Those who came to America from 1965 onwards set out to achieve “the American Dream,” the exact meaning of which could be debated but generally connoting economic freedom and good education for children with the goal of becoming a part of “mainstream America.”

This mentality persisted for a long time, until SAIGU. SAIGU, literally meaning April 29 in Korean, is a term used in reference to the 1992 LA Riots/Uprising, which broke out after the acquittal of policemen tried for brutally beating Rodney King.[iii] Leading to the verdict of Rodney King, major news outlets diverted issues of systemic racism and police brutality by playing up the murder of Latasha Harlins and disproportionately highlighting racial tensions between Koreans and Blacks in South LA. Many believe that such misled reporting fueled targeted anger towards Korean businesses during the riot/uprising. In fact, there is reasonable suspicion that the LAPD abandoned Koreatown despite repeated requests from merchants and community leaders, and instead using Koreatown as a shield to protect wealthier neighborhoods like Beverly Hills.

As a result, over 2,300 stores owned by Korean merchants in South Central and Koreatown were attacked, looted, and burned down.[iv] Most were uninsured and few received adequate compensation.[xiii] Overnight, the “American Dream,” or the fantasy of it, dissipated with the smoke.

SAIGU forever changed the psyche of Korean Americans. Many called it a moment of reckoning. In CHOSEN, Richard Choi of RadioKorea, who live-broadcasted events on the ground during the riots, states that before SAIGU, Koreans were just immigrants living in America. After SAIGU, Korean immigrants became Korean Americans. Hence, the definition of the American Dream fundamentally changed from one based on economic freedom to another based on community consciousness and political representation. This is the foundation upon which CHOSEN begins.

Personally, SAIGU was life-changing because prior to learning of the significance of SAIGU in connection with the formation of Korean American identity, I simply didn’t know what to make out of my identity as Korean in America. Although I was born in Minneapolis, my family left for Korea when I was three and I grew up there until I was 17.

When I returned to the US shortly before my 18th birthday, after renouncing my Korean nationality because dual citizenship is prohibited in Korea, my identity crisis began. I wondered whether I was supposed to renounce my “Koreanness,” just like my Korean nationality, and become as Americanized as possible. I then wondered what that Americanness was. Was being Korean or preserving Koreanness, whatever that means, a baggage— something I needed to shed or hide— or is this something to be celebrated and respected?

My long existential query ended when I learned of SAIGU. I realized, for the first time, that there can be a Korean American identity, one grounded on both Korean and American cultures and values, and one that calls for active participation in our society with a sense of community consciousness. Most importantly, the idea that our collective identity is one in the making and that we can all contribute to its evolution and formation truly inspired me. I felt like I was given a mission to help cultivate and refine it with my Korean American peers. All of this learning came from a workshop led by KW Lee, who opens the first scene of CHOSEN. I filmed his fierce speech as a college kid back in 2005, and I wanted to begin the film with him to acknowledge the very moment of my own enlightenment.

On whether there were other turning points in which the Korean American community or its identity was significantly impacted, I think we are living it now. 30 years have passed since SAIGU and yet we are living through another period in which the legitimacy of our belonging in America is being questioned. I think the recent rise of Asian hate crimes,[xiii] as reprehensible as it is, will be marked as a transformative moment in history. A silver lining to this tragedy would be that the younger generation is calling for pan-Asian solidarity and political representation, an ideal that has never quite materialized in the past.

The concept of AAPI identity certainly existed in the past, but the depth of solidarity between different Asian ethnic groups was rather tenuous. Without a doubt, spanning from the Chinese railroad indentured servitude to the Japanese internment camp, and from Free Chol Soo Lee movement to the death of Vincent Chin case, and from SAIGU to the recent Asian hate crimes, there has been consistent and pervasive anti Asian racist sentiments in America. But perhaps with the exception of the Free Chol Soo Lee movement, a large-scale, consciously pan-Asian solidarity was not frequently seen.

However, shortly after the outbreak of COVID-19, we woke up to a series of news and graphic images of Asian elders and women being violently shoved and attacked in public. For months, by virtue of our Asian heritage, we were subjected to a group trauma and a sense of powerless victimhood, giving rise to urgent calls for a more unified and expansive AAPI identity as a force to be reckoned with.

I wonder whether a generation or two from now on, my offspring will regard themselves no longer as specifically Korean American but rather as members of the larger Asian America. I wonder whether that would be desirable, to lose an ethnic-specific identity by embracing a perhaps more bland yet continuously evolving and inclusive bloc of various identities that fall under “Asian.” I am value-neutral on this hypothetical but this is something I started actively deliberating as of late. Perhaps this is a topic for another day.

AAPR: You’ve noted that you drew inspiration for the film from a memoir by former US national security adviser John Bolton, which made you realize that “the fate of an entire country” could be dictated by a handful of US politicians, and made you wonder whether, if those positions were held by Korean Americans, they “might have rendered a more favorable policy toward peace.”[vii] How did your experience of making the film change or reinforce your perspective on that question?

JUHN: I don’t think I would’ve arrived at that hypothesis— whether Korean American elected officials can render a more favorable decision for their motherland— had I not been interested in the US’ relationship with the Korean peninsula. I am emotionally invested in what happens in the Korean peninsula— both North and South— not least because my parents and friends live there (in the South) but more importantly because I consider peace in Korea to be the zeitgeist of our generation.

While it is true that reading John Bolton’s book sowed a seed that later blossomed into CHOSEN, I realized as soon as I started shooting the film that the dominating spirit of CHOSEN would not be exploring US-Korea relations but rather getting to the depths of the complex realities of the Korean American community.

That said, to directly answer the question, my hypothesis was not entirely correct. Two of the four elected Korean American Congressmembers vehemently opposed a bill that would’ve declared the end of the Korean War. I wasn’t necessarily surprised at the direction of their decision, but the degree of the ferocity of their opposition was surprising. They didn’t just oppose the bill— they led a movement in the GOP to do so. This may be a ra sensitive claim, but I find it ironic that completely uninformed and impulsive American politicians on Korean issues, i.e., Trump, could arrive at the same conclusion as well-versed Korean American politicians with a certain ideological leaning.

The rationale behind the decision to oppose the declaration to end the Korean War merits some explanation. Generally speaking, those who lean conservative in Korea and in the US tend to reject any reasonable attempt at peace talks with North Korea because North Korea is perceived to be evil with its cruel disregard for people and human rights violations.

To be clear, there is a lot of truth to this claim. North Korea is at fault for grossly mistreating its citizens. But what is perhaps equally problematic is the way in which the conservatives have uncritically adopted the anti-communistic worldview to prevent any sensible approach to peace talks. Historically, such anti-communism was actively exploited by the military dictators in South Korea to quell more progressive dissidents, who were often painted as North Korean sympathizers, if not outright spies. This history of violent abuses of power by the South and the corresponding anti-communism throughout the latter half of the 20th century continues to reverberate in South Korea; one could even argue that South Korea’s latest President Yoon was born out of such anti-communistic rhetoric. As such, any Korean or Korean American politician in the position of power whose outlook is deeply grounded in anti-communist conservative ideology may render hostile policies towards the North, the rationale of which might differ from their uninformed American political counterparts but the outcome, unfortunately the same.

I am not necessarily making a value judgment here but attempting to explain the rationale behind the split of the votes among Korean American House members on ending the Korean War. In sum, whether Korean American politicians can render a more peaceful approach and policy towards the Korean peninsula remains to be seen.

AAPR: You’ve described yourself as a “diasporic storyteller” and remarked that your encounter with descendants of Korean ancestors in Cuba answered your “lifelong query on what it ‘mean[s] to be a member of the Korean diaspora–those who lived outside their home country.’”[viii] What does being a member of the Korean diaspora mean to you, and how has this meaning evolved over the years?

JUHN: If learning of the 1992 SAIGU served as my enlightenment to the idea of a Korean American identity, a serendipitous encounter with Korean Cubans during my backpacking trip to Cuba exploded my interest in the idea of diaspora.

Prior to my trip to Cuba in 2015, I’d had frequent and wide exposures to various Korean communities around the world, whether it be Korean Chinese (Joseonjok), Korean Russian (Koryosaram), Korean German, Korean Brazilian, Korean Japanese, Korean Argentine, or even Korean South Africans. I’ve long wondered how to understand their existence in relation to mine, how their immigration history differs from mine, whether we could build solidarity with one another in times of crisis, and ultimately, how to perceive our relationship to the motherland. I felt incredible empathy and affinity towards other members of the Korean diaspora who have long struggled to make sense of their own existence and those who continue to survive and thrive as ethnic minorities and immigrants in their own respective host countries.

If my previous identity query was grounded on, and perhaps confined by, this dualistic tension between Korea and America, the idea of diaspora liberated me from a geographic grounding of identity. It was a membership not only in the Korean or Korean American community but also in these larger sojourner communities around the world who share, no matter how remote or accurate, collective memories of the homeland, heritage and history.

While one may perceive such a take on identity as too ethnocentric or nationalistic in nature, in truth it’s quite the contrary: it is a universal and expansive one. A healthy diasporic identity is constructed not at the expense of one’s membership and commitment to a home country but in addition to it. Not only am I Korean, Korean American, or Asian American— I’m also a part of the larger Korean diaspora.

A diasporic storyteller, therefore, has a perspective that transcends the confinement of one’s own community. It’s a perspective that allows for both participation and observation. It’s a perspective that is both empathetic and critical. It’s a perspective that is both local and transnational. It’s a perspective both particular and universal in nature. Or at least that’s the kind of perspective I aspire to attain.

AAPR: You’ve observed that whenever you travel back to Korea, you are often questioned as to “how authentic [you are] in terms of [your] ‘Koreanness,’” and that one question this experience raised for you was, “What kind of relationships should exist between the people from the home country and people who live outside (of it)?”[xi] In the fall, you toured South Korea for the premiere of CHOSEN. What are your reflections on these questions in light of this most recent tour? How did South Korean audiences respond?

JUHN: According to the annual Best Countries Report carried out by the U.S. News and World Report in 2023, South Korea ranks as the 9th most “racist” country out of the 79 countries surveyed for the report.[x] South Korea is also the only OECD developed country among the top 22 countries on the list.[xi] In the 2017-2022 World Values Survey, over 20% of residents surveyed in Korea responded that they don’t want non-Koreans as their neighbors.[xii]

Equally problematic is Koreans’ hostile or stigmatized view of members of their own Korean diaspora, in particular Korean Chinese, North Korean defectors, Korean Russians, Korean adoptees, Korean Japanese, and biracial Koreans, to name a few. Considering that over 7 million ethnic Koreans live overseas,[xiii] which accounts for roughly 13% of South Korea’s population of 52 million,[xiii] such “othering” of their own diaspora is quite troubling.

Perhaps this is a testament to Koreans’ narrow and rigid definition of who Koreans are. Fluency in the Korean language, pure-bloodedness, nationality, residency, or service in the military are some of the more important elements that “qualify” one as an “authentic” Korean.

In that regard, my case is an anomaly. Although I am a US-born American citizen, I speak fluent Korean, both of my parents continue to live in Korea, I spent close to half of my life there, and my knowledge of Korean history and culture is more or less up to par with average Koreans. My repeated appearance in Korea’s popular internet radio program, “News Factory,”[xv] also earned me special recognition and spotlight whenever I participated in public screening events. In short, what I experienced as a member of Korean diaspora was not the norm but an exception.

I shared CHOSEN with at least a couple of thousand audiences through dozens of public and private screenings. At almost all screening events, people commented how little they knew about the history and current state of Korean Americans and how surprised they were watching the footage of the 1992 LA Riots and Korean Americans’ continued struggles for political representation in light of the ongoing Asian hate crimes.

This goes on to prove a couple of important points. First, there’s a lack of education when it comes to diaspora and multiculturalism. Though there is some push by the government to foster multiculturalism in primary education in Korea, one of the main criticisms of this initiative is that it focuses too much on assimilation and too little on recognizing and celebrating differences among diverse ethnic members in the Korean society.

Second, similarly, there is a lack of fair portrayal of members of the Korean diaspora in news reporting and popular mediums such as film, drama, and TV programs. For example, Korean Chinese and North Korean defectors are frequently depicted as a threat to society, while Korean adoptees, biracial Koreans, labor migrants and South East Asian wives are painted with pity or social stigma.

A great number of Koreans live overseas as immigrants, ethnic minorities, foreigners, and aliens whose livelihood and well being depends, in part, on the hospitality of host nations. Such hospitality is usually not reciprocated to those coming, or returning, to Korea. Of course, I am oversimplifying complicated matters that deserve more detailed research, but it is worth deliberating whether the notion of “authentic Korean identity” is real and morally legitimate, especially when it seems to largely function as a dividing mechanism.

AAPR: You’ve mentioned that the motivation for you to study film and law are the same: to share stories of social causes and be an agent of change.[xvi] How does your background as a lawyer inform your perspective, your work, and the mark you want to leave on the world?

JUHN: The funny thing is I never made a conscious decision to leave law altogether to become a career filmmaker. JERONIMO[xvii] was a project I started by chance— a passion project, rather. But my life panned out differently. While there is no denying that making JERONIMO and CHOSEN changed the course of my life, largely positively but also with some financial difficulties, I still think about other career options, not because I dislike storytelling but because independent filmmaking is a pragmatically difficult career to sustain.

I don’t think my training in law necessarily had a meaningful effect on my perspective or my work as a documentary filmmaker. If it did, it would be only marginal at best. I say this because I never practiced the kind of law, such as human rights, civil rights, or immigration law, that could have enhanced my understanding of social justice, empathy, and compassion.

I would like to believe that what I am doing is worthy not only to my own sense of fulfillment and growth but also to those who seek identity grounded in humanity, hybridity, and hospitality, all of which I regard to be core tenants of a diasporic identity.

AAPR: One powerful aspect of the film is the unflinching portrayal of intense conflict among candidates across wide swathes of the political spectrum. You’ve mentioned that you are curious to see if CHOSEN will inspire other AAPIs to run for political office “no matter which ideological spectrum they fall in.”[xviii] How do you think of your role as filmmaker and Korean American in potentially emboldening voices you might disagree with?

JUHN: This is a difficult question to answer. As much as CHOSEN is about addressing a need for AAPI political representation, it is also about questioning what drives people to run for politics and why one fights for certain beliefs and values. Although David Kim in CHOSEN is far from being a perfect candidate, the film does present David’s journey as a case for hope. Whether or not I agree with David’s policy and political positions, I find something inspiring about his campaign, particularly his heart for the marginalized, the voiceless, and the community. This is not to say that I found other candidates’ intentions as disingenuous— I think all five candidates in CHOSEN, irrespective of their ideological leanings, have genuine convictions about their political ambitions.

With respect to future AAPI candidates whose political positions I may disagree with, I think the real issue may be questioning the source from which their convictions arise. If the conviction comes from universal values that we can generally all agree upon, the case is moot. However, if the conviction, or the direction of their policies, is triggered by hatred, fake news, racism, bias, propaganda, overt narcissism, or ill intended guidance, then I would openly address my concern and protest if necessary. The more difficult and relevant question might be questioning the extent to which we would espouse identity politics. I would absolutely love to see more Asian American political leaders, but what if our representation is achieved at the expense of other similarly vulnerable communities? How do we not succumb to tribalism but strive to uphold universality? These are difficult questions, yet we need to continue to wrestle with them.

AAPR: You’ve quoted Korean philosopher Choi Jin-seok, who said: “The only time when a being exists, is when that person questions and not when he answers.”[xix] What questions are on your mind these days? What questions should young policymakers, lawyers, creatives, or other aspiring changemakers be asking?

JUHN: One question that is at the core of CHOSEN was this: “How can we peacefully coexist amidst our differences?” One might remember that 2020 was not an ordinary year— COVID-19, racial tensions, economic turmoil, and a chaotic political environment led by Trump, all contributed to a feeling of doomsday.

The question is still valid, albeit to a lesser degree now, and I continue to struggle with it. What would be the moral and philosophical tools or ideas that could help bring a basic sense of camaraderie, unity, and hospitality in this world? Is that too lofty of an ideal? My hypothesis is to explore this idea of diasporic identity and consciousness through storytelling.

AAPR: Any final thoughts you’d like to share with AAPR readers?

JUHN: Continuing the theme of diasporic identity and ways of life, I would like to leave with a quote from Hugh of Saint Victor who was a 12th century French theologian, which I believe perfectly captures the essence of diasporic consciousness:

The person who finds his homeland sweet is still a tender beginner; he to whom every soil is as his native one is already strong; but he is perfect to whom the entire world is as a foreign place. The tender soul has fixed his love on one spot in the world; the strong person has extended his love to all places; the perfect man extinguished his.[xx]

Endnotes

1 See Seung-hyun, Song, “Korean American director on why he followed five US politicians of Korean descent,” The Korea Herald, 10 November 2022, https://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=2022111

0000774.

2 “History of Korean Immigration to America, from 1903 to Present,” Boston University School of Theology: Boston Korean Diaspora Project, accessed April 12, 2023, http://sites.bu.edu/koreandiaspora/issues/history-of-korean-immigration-to-america-from-1903-to-present.

3 See Saigu Campaign, accessed April 12, 2023, https://www.saigu429.org.

4 See Seo, Diane, “COVER STORY : Fire and Pain : The Riots Left About 2,300 Korean-American Business Owners Reeling From More Than $400 Million in Damage. Although the Scars Show Little Signs of Fading, Community Leaders Acknowledge That the Unrest Helped Unite Them.,” Los Angeles Times, January 31, 1993, https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1993-01-31-ci-1199-story.html.

5 See Yang, John, “HELP FOR L.A. BUSINESSES HAS BEGUN, BUT TO SOME IT SEEMS TOO LATE,” Washington Post, November 18, 1992, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1992/11/18/help-for-la-businesses-has-begun-but-to-some-it-seems-too-late/20113b36-1f0f-4f24-b34a-d810b2d16899/.

6 See The Associated Press, “More Than 9,000 Anti-Asian Incidents Have Been Reported Since The Pandemic Began,” NPR, August 12, 2021, sec. National, https://www.npr.org/2021/08/12/1027236499/anti-asian-hate-crimes-assaults-pandemic-incidents-aapi.

7 Jian, Lee, “Director Joseph Juhn tells multi-layered story about Korean-Americans in U.S. politics,” Korea JoongAng Daily, 6 November 2022, https://koreajoongangdaily.joins.com/2022/11/06/entertainment/movies/Korea-Chosen-Korean-American/20221106151232174.html.

8 MacDonald, Joan, “‘Chosen’ Follows 5 Korean American Candidates Who Ran For Congress,” Forbes, 6 March 2022, https://www.forbes.com/sites/joanmacdonald/2022/03/06/chosen-follows-5-korean-american-candidates-who-ran-for-congress/?sh=481197622298.

9 MacDonald.

10 “Most Racist Countries 2023,” accessed April 12, 2023, https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/most-racist-countries.

11 “Most Racist Countries 2023.”

12 “WVS Database,” accessed April 12, 2023, https://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSDocumentationWV7.jsp.

13 외교부, “다수거주국가 | 재외동포 정의 및 현황 외교부,” accessed April 12, 2023, https://www.mofa.go.kr/

www/wpge/m_21509/contents.do.

14 “South Korea” in The World Factbook (Central Intelligence Agency, March 30, 2023), https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/korea-south/.

15 See generally Lim Jang-won, “[Newsmaker] With Mayor Oh in Office, Eyes Are on Kim Ou-Joon of TBS’ ‘News Factory,’” The Korea Herald, April 18, 2021, https://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20210418000189.

16 Fung, Stephanie “A #hyphenatedAsians POV: Joseph Juhn – Chosen Documentary – The Universal Asian,” February 15, 2021, https://theuniversalasian.com/2021/02/15/interview-with-joseph-juhn-chosen-documentary/.

17 “Jeronimo the Movie,” accessed April 12, 2023, https://jeronimothemovie.com/.

18 MacDonald, “‘Chosen’ Follows 5 Korean American Candidates.”

19 Fung, “A #hyphenatedAsians POV.”

20 “Quote For The Day,” The Atlantic, May 10, 2009, https://www.theatlantic.com/daily-dish/archive/2009/05/quote-for-the-day/202079/.