BY JENN MENN

This piece appeared in our 2015 print journal. You can order your copy here.

Introduction to the foster care crisis

In the whirl of a brief phone call, a social worker’s car doors shutting in the driveway, and signing a custody paper like a FedEx package, I became mom to three little strangers. My husband and I served as foster parents and quickly fell in love with Eddie, Kayla, and Nike (ages four, two, and nine-months). T.J. also worked full time for the Army, and I stayed at home with the kids while a college student. Throughout our first year of foster parenting we served seven children.

Children become foster children when the state determines the child at risk of severe harm from exposure to abuse, abandonment, or neglect. A teacher, neighbor, or policeman likely made a report of suspected abuse, and then an investigator with Child Protective Services determined the child needed to be removed from the caregiver—usually a parent. If the investigator cannot find suitable care for the child within the caregiver’s family, then the child comes to be placed in foster care with strangers. Many of these children will return to be with their parents or family members once the situation is safe, but some end up in full-custody of the state, whereby they become available for adoption.

Our county, like many across America, faced an ongoing shortage of foster families for children who need protection. There were 60 families for 310 children. So even though T.J. and I were under twenty-five years old in a thousand-foot bungalow with three kids, we received a letter from our county director pleading with us to consider expanding the amount of children we would take in. When the county ran out of home options, children lived in facilities like orphanages or moved to placements across the state.

Communities often have families willing and able to foster parent, but barriers limit their involvement. Some barriers, such as the lengthy process to certify as a foster parent, ensure the safety and well-being of children in care.[i] Other policies, such as lack of state-to-state reciprocity for families, create burdensome and limiting barriers. When foster families move across state lines, their hard work towards certification starts over again because states lack a compact of reciprocity.

Becoming a foster parent

The process to certify as a foster parent is lengthy and similar in all states. The majority of families who start the process do not end up completing it. Here are the stages:[ii]

- Initial request to volunteer: Families sign up via phone or at an awareness event to attend a meeting. Some states offer training only through the public government agency and others also contract with private agencies to recruit and manage foster parents.

- Informational meeting: These two-hour sessions intend to answer frequent questions which generally screen out many people. They are offered quarterly or monthly in most counties.

- Classroom training: Parents prepare for the children, families, systems they’ll engage with. It ranges 25-30 hours in class. Some states can complete this training over a couple weekend intensive sessions and other state agencies have policies about the classes needing to be spread an evening a week over months to provide time to learn.

- Formal application: Fifty pages include contact information for references, submitting financial information, family history, and answering relevant questions.

- Tests: A medical physical, updated immunizations, tuberculosis test, fingerprinting for FBI background checks in every state resided and drug tests are completed for all members of the household, examinations and updated shots for any animal. These are usually done at the personal expense of families.

- Home inspections: Department of Health inspects the home, as well as sewer inspection if relevant. The child placement agency’s social worker will also inspect the home layout, cleanliness, checklist of about 100 requirements including location of supplies, certain furniture, water temperature limits, and types of locks.

- Three home visits by a social worker specially licensed for the “home study” task: The first is for understanding family motivations and interests as well as general usability of the physical home; the second will analyze psychological health, grievances as parents, and fertility history; the final inspects the home and have a discussion on age, number of children, race, and willingness to take in children with special needs. Finally, the home study professional writes a 10-14 page home-study on the fitness of the family to foster and submits the full gathered binder of materials for the various levels of management to approve. The approval process alone averages over a month (It took 10 weeks for TJ and I reopening our home).

The process rarely goes efficiently. Long gaps of time in between calls or meetings or abrasive interactions with overburdened staff compound the frustration people experience when trying to volunteer. Emotionally, families often feel vulnerable and full of uncertainty, both about whether they will measure up or be misunderstood, and who the future foster children will be. Becoming a foster parent has a high transaction cost, which makes sense that of twenty-eight families who determine they’d like to adopt from foster care, only one makes it through.[iii]

For TJ and me, the process defined six months of our life. Once certified, within a week we received a call asking us to become mom and dad to frightened little Eddie, Kayla, and Nike. While the caseworker thought they’d be with us at least a year, an aunt from out of state heard about the children, drove twelve hours to attend court, and ended up with the three children in her custody within three weeks of them entering our home.

A pathway for children to move between states: ICPC

While a surprise to T.J. and me, the children’s swift placement with an out-of-state aunt was a major feat made possible by an Interstate Compact for the Placement of Children (ICPC). This agreement between states allows children to be placed with family out of state.

If children have responsible kin who can care for them, it is often the least shattering and most permanent option for children removed from parents. Living in foster care can be stressful in the lives of children for many reasons, one of which is the sense of limbo with changing caregivers. Statistically, children in foster care without a family while in custody remain vulnerable citizens even after they leave foster care: victims of sex trafficking, substance and relational abuse, homelessness and criminal activity.[iv] Current social work theory in America places the best cases for a child on a spectrum like the one below:

While state involvement in foster care began in the late 1800s, kinship placements could only happen in the same state until ICPC passed in the early 1960s. For example, if a boy came into the care of New York and had grandparents willing to care for him in Connecticut, they were out of luck. This was in large part due to unknowns about state responsibility for the logistics and funding of the transfer. Families could not penetrate these bureaucratic barriers and as a result children languished in emergency shelters.

These barriers were mostly overcome with the development of ICPC. Since foster care is managed at the state rather than federal level, each state legislature individually passed a uniform law that set up an office to facilitate the movement of children across state borders to families. The compact created an independent association, now under the American Public Human Services Association (APHSA), that handles the necessary paperwork to certify kin and adoptive families as well as communicate ongoing funding needs. The compact currently remains the sole means of moving foster children between states. [v]

The policies under ICPC help children, though its implementation and scope have room for improvement. Approximately 40,000 requests a year are made by social workers for children to move with families in different states.[vi] To improve implementation, in 2013 the federal government granted the Administration of Children and Families in partnership with the ICPC administration funds to pilot an online database to facilitate quicker approvals.[vii] This new system, called National Electronic Interstate Compact Enterprise, or NEICE, makes movements easier and creates opportunity to expand the use of exchanging certification information.

A Potential Pathway for Families

The ICPC only recognizes out-of-state family certifications when the state is determining if the best interest for a certain child is to move across borders.

Families relocating or living across state borders who may be in the best interest of children broadly are beyond the current scope. For example, while we had foster children, The Army ordered my husband to move across the country. We facilitated a transition of the foster girls who needed to stay local, packed up, and TJ and I resettled in a new state. No process is available to transfer our certification as foster parents, though if the girls would’ve come with us in the process of adoption, ICPC could have facilitated that.

When I brought our home study to the county office and offered our services, a social worker shuffled through the material and said our training would reciprocate, but we would need to redo all the other elements. Certification in our new home state took six months.

If ICPC offered family transfers through their online system, the receiving state could evaluate the certification much quicker. The new home would be inspected, but the other six out of seven stages are unchanged. States could also share their notes on the history of service as a foster parents such as quality of care and continuing education. This would save time and offer children experienced foster parents. To establish this sort of reciprocity for all foster families in the United States, a uniform home study and training format would be helpful, which ICPC administrators are working toward.[viii]

I shared from my perspective as a relocating family, but the implications for inter-state reciprocity would benefit many urban areas. Several cities with concentrated amounts of foster children (such as New York City, Washington D.C., St. Louis, Chicago, and Kansas City) border more than one state, making interstate reciprocity all the more relevant. Suburbs in Virginia, for example, have been known to have a surplus of families offering to care for children for their own region, but they cannot be of help to the hundreds of children in Washington D.C.[ix] Foster families are an American asset, but right now they are filed away in state drawers while children wait without families. Millions of families who move between states represent socially mobile, college-educated, and racially diverse families—qualities which make strong foster families.[x] “People employed by the Armed Forces [like us] had the highest mover rate of any employment status, with 72.7 percent [over five years].”[xi]

I attribute the lack of collaboration with family certifications to uncertainty about how to mitigate policy differences, liability or confidentiality concerns, and status quo bias. Each state differs in details for determining a suitable foster family.[xii] Trainings have different names and home studies take differing measures, so certifications are not immediately compatible to transfer into data systems. States such as Illinois cannot even legally use web-based systems to communicate any confidential information with regards to foster care. Lawsuits can be brought against the state for injustice that happen with a state licensed foster parent, so social work professionals may be leery of approvals which they did not oversee.

These behavioral hesitations are worth overcoming. Besides the differential in wellbeing outcomes for children in families over facilities, lack of reciprocity costs receiving states unnecessary tax dollars. The cost ratio of a child in a facility versus a foster home is 10 to 1.[xiii] So since T.J. and I averaged serving three children at a time, the four months T.J. and I waited for re-certifcation is the equivalent to costing the state over $52,000. In California, where foster child populations are great, the difference over four months would cost $95,000. The administration of ICPC is a fixed cost for states, so maximizing the utilization of its capabilities benefits the state.[xiv]

Recommendations

Policy makers can support their nation’s children and front-line staff with a simple amendment to facilitate foster family moves through ICPC.

Overall, I recommend the current agreement for ICPC create an amendment for the administration of movement of families and vote on it during the annual administrative meeting. The piloting of the online system NEICE[xv] makes the time ripe to improve the management of foster parents between states. In preparation for the national database, states’ Childrens’ Bureaus should recognize foster parent certification from other states and move towards a uniform certification process.

The amendment would allow for ICPC to transfer specific foster family information to a new state. Information exchanges for children moving between states happens for specific children with specific home prospects—the identified sending county with the boy and receiving county where the grandparents are exchange the information through their state ICPC office. Since the process already is in place for specific communications on certifications, the only work the amendment would create is the use of the data system to transfer information.

For immediate impact, the amendment can include a waiver for military families: If a military family has a home study and foster parent or adoptive certification in one state, it transfers to another.

State and federal legislatures can address the issue too. ICPC is renewing its compact through state, and possible federal, legislatures as a bill to streamline the process and modernize beyond what administrative amendments can approve.[xvi] While the proposal contains guidance for unified home study and online database, I recommend any legislative supports insist inter-state family certification transfers be included as part of approving the new compact.[xvii]

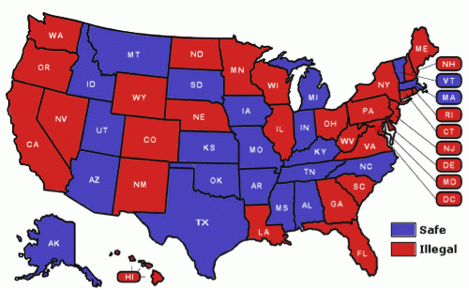

At the very least, I recommend a clear reciprocity chart for states to easily compare other state certification requirements. These interactive maps are available for teachers certification and gun permits to see which states have similar requirements and therefore honor the out-of-state permit.[xviii]

Social workers who manage home studies and foster families need an accessible reciprocity chart to be able to quickly re-evaluate experience foster families coming in from out of state. I recommend this including a comparative chart on the Child Welfare Information Gateway for social workers and AdoptUS.org for families.

Final Remarks

Creating avenues for inter-state foster families will be one important step towards ensuring every child has a family.[xix] With 500,000 children in foster care, and over 88,000 living without families, collaboration will be key to solving the crisis of children in need.[xx] ICPC laid the foundation, and now it needs innovation.[xxi] With inter-state reciprocity, current foster families who need to move will be able to continue their public service and meet the needs of children. More so, potential families near urban areas with many children in need would be a strong resource. Removing this one barrier would encourage involvement and allow social workers to devote more of their time to recruiting and certifying new families.

T.J. and I move to a new state after graduation, and will face groundhog’s day again as we recertify as foster parents. As we gather the same paperwork, sit through the same classes, answer the same questions, and take deep breaths during the same silent eight-week processing time, I pray that the children in the emergency shelter down the road know it’s not that they’re not wanted.

Jenn Menn is a mid-career graduate of the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University and currently a foster mom to four children. She and husband T.J. have parented twenty-two foster children, and their memoir, entitled Faith to Foster, releases this summer.

Photo by user Annie Spratt via Unsplash

[i] For a sample explanation or requirements, see Oregon’s sixty-five page guide, “Standards for Certification of foster parents and Relative caregivers and approval of potential adoptive resources” https://apps.state.or.us/Forms/Served/de9303.pdf

[ii] Children’s Bureau/ACYF/ACF/HHS, “Home Study Requirements for Prospective Foster Parents.” https://www.childwelfare.gov/pubPDFs/homestudyreqs.pdf

[iii] Julie Wilson and Jeff Katz. Listening to Parents: Overcoming Barriers to the Adoption of Children from Foster Care ( Cambridge: Harvard Kennedy School, 2005). http://www.hks.harvard.edu/ocpa/pdf/Listening%20to%20Parents.pdf

[iv] The “Preventing Sex Trafficking and Strengthening Families Act” passed in 113th Congress. https://www.congress.gov/bill/113th-congress/house-bill/4058?q=%7B%22search%22%3A%5B%22preventing+sex+trafficking%22%5D%7D

[v] James O’Donnell (Vice President of the Association of Administrators of the Interstate Compact on the Placement of Children), interview by author, January 23 2015.

[vi] Vivek Sankaran. “Foster Kids in Limbo: The Effects of the Interstate Compact on the Placement of Children on the Permanency of Children in Foster Care.” http://www.throughtheeyes.org/files/ICPC_Annie_E_Casey_Report.pdf

[vii] Anita Light and Mical Peterson. “APHSA and AAICPC Launch Transformation Pilot with Federal Support” in Policy and Practice April 2014. http://www.aphsa.org/content/dam/AAICPC/PDF%20DOC/Feature%202-AAICPC.pdf

[viii] “Interstate Compact on the Placement of Children” in A Pathways Policy Brief http://www.aphsa.org/content/dam/AAICPC/PDF%20DOC/Home%20page/ICPC-Policy-Brief.pdf

[ix] Department of Health and Human Services, Children’s Bureau.“Home study requirements for prospective foster parents. Washington, DC: U.S.” in Child Welfare Information Gateway (2014)

[x] David Ihrke and Carol Faber. “Geographic Mobility: 2005 to 2010.” in United States Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/prod/2012pubs/p20-567.pdf Page 6.

[xi] “American Community Survey” in Census Bureau https://www.census.gov/hhes/migration/data/acs/state-to-state.html

[xii] : Gonyea, Bachman, Rajabiun, Springwater, Tobias, Hirschi, and Little. “The 50 State Chartbook on Foster Care” in Boston University School of Social Work www-staging.bu.edu/ssw/usfostercare

[xiii] California Department of Children Services. “Foster Care Rates Group Home Facility Listing” (3 February 2015) http://www.childsworld.ca.gov/res/pdf/GHList.pdf and

DeVooght, Child Trends, and Dennis Blazey. “Family Foster Care Reimbursement Rates in the U.S.” (9 April 2013) http://www.childtrends.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/Foster-Care-Payment-Rate-Report.pdf

[xiv] James O’Donnell interview

[xv] Association of Administrators of the Interstate Compact on the Placement of Children “National Electronic Interstate Compact Enterprise” http://www.aphsa.org/content/AAICPC/en/actions/NEICE.html

[xvi] Association of Administrators of the Interstate Compact on the Placement of Children. “New ICPC” with proposed legislative language and enactment progress http://www.aphsa.org/content/AAICPC/en/NewICPC.html

[xvii] James O’Donnell interview

[xviii] “Reciprocity” Hudson Valley: Firearms Certification. http://hvfirearmscertification.com/reciprocity/

[xix] AFCARS 2006 Data, http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/cb/resource/about-afcars

[xx] AFCARS 2006 Data

[xxi] Vivek Sankaran. “Foster Kids in Limbo.”