As the battle for the liberation of Mosul enters its final stages, attention is beginning to turn to what a post-ISIS Mosul, and Iraq in general, would look like.

But while it is widely assumed that it is incumbent upon the international community to help this process, full state administration and oversight is not on the cards for policymakers in the United States or any other country. The question on everybody’s lips is whether Baghdad can ensure that Mosul will be effectively rebuilt and incorporated into a post-ISIS Iraq. Most commentators and policymakers have expressed their discontentment with the policies of Baghdad, which they see as too Shia-centric, too much under the influence of Iran, and/or totally incompetent.

Although it may be fashionable in certain policy-making circles, this idea of total incompetency is dangerous and destabilizing. Where does this assumption come from? This article seeks to explore the historical roots of the phenomenon, and investigate how this dangerous assumption needs to be challenged. Full Iraqi agency is essential if there is to be any chance of lasting stability in a post-ISIS Iraq.

Sadly, Iraq has become synonymous with violence and destruction. It has frequently been depicted as a war-torn area, previously under the control of a brutal dictatorship, before that an incompetent king, and even before that in the throngs of a brutal Ottoman despot. Parts of the international community have made it abundantly clear that it is their duty to abate this situation. However, while humanitarian interventions like the relief of Sinjar have undoubtedly saved lives, constant foreign intervention, whether it be the US occupation starting in 2003 or the deployment of Turkish forces near Mosul to combat “terrorist activities”, has obstructed the Iraqis’ ability to freely govern themselves.

So, what are the historical roots of this distrust? The modern state of Iraq was a British colonial creation carved out of the three regions of Mosul, Baghdad, and Basra. Under British administration, the Kingdom of Iraq was established in 1921. At the end of the First World War, British policymakers sought to control these three areas in large part to guarantee imperial communications with India, even if the political climate at the end of the war did not allow for open colonial acquisition of territory. In line with the principles of Wilsonian liberalism, a narrative of liberation had to be constructed. In other words, these three areas needed to be shown to be in need of foreign assistance and liberation from tyranny, if Britain had any chance of convincing international public opinion that an acquisition of these areas was necessary.

An example of the shaping of this narrative can be seen in a proclamation issued four years earlier, when British soldiers “liberated” Baghdad from Ottoman control. The leader of the British forces there, General Maude, issued leaflets to the residents of Baghdad stating:

Since the days of Huleku your citizens have been subject to the tyranny of strangers, your palaces have fallen into ruins, your gardens have sunken into desolation and yourselves have groaned in bondage… it is the wish not only of my King and his peoples, but it is alone the wish of the great nations with whom he is in alliance that you should prosper.[1]

It was up to the British to supposedly restore them to their former glory and live up to the epithet of the “cradle of civilization.” The mentioning of Huleku, the Mongol khan who destroyed Baghdad in the 13th century, fed in to this British demonization of the Turk and its desire to liberate the poor, subjugated Arab. By regurgitating notions of Arab subjugation under foreign Turkish rule, the British portrayed themselves as the ultimate liberators.

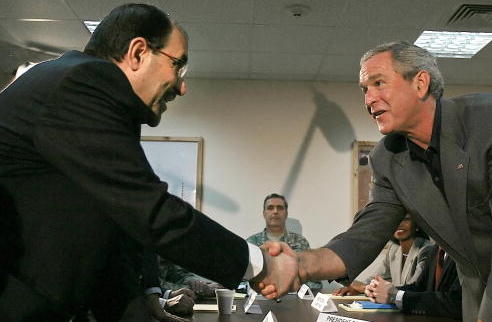

Out of context, this proclamation seems merely a historical artifact, not important to the modern political climate. However, in 2003 former US President George Bush, in two separate speeches, eerily echoed this notion of altruistic liberation from a tyrannical despot:

Many Iraqis can hear me tonight in a translated radio broadcast, and I have a message for them. If we must begin a military campaign, it will be directed against the lawless men who rule your country and not against you. As our coalition takes away their power, we will deliver the food and medicine you need. We will tear down the apparatus of terror and we will help you to build a new Iraq that is prosperous and free. In a free Iraq, there will be no more wars of aggression against your neighbors, no more poison factories, no more executions of dissidents, no more torture chambers and rape rooms. The tyrant will soon be gone. The day of your liberation is near.”[2]

“In the images of celebrating Iraqis we have also seen the ageless appeal of human freedom. Decades of lies and intimidation could not make the Iraqi people love their oppressors or desire their own enslavement.”[3]

References to terror, slavery, and liberation bear striking resemblances to the proclamation issued by General Maude. The American’s Turk was Saddam Hussein. Their long period of disrepute was Saddam’s 24-year rule, which they argued had brought the country of Iraq to its knees. Again, Iraqis were again portrayed as weak, defenseless and needing foreign intervention. While not the initial reason behind the invasion of Iraq in 2003, the narrative quickly shifted to one of liberation from tyranny and the encouragement of a western-style democracy. True, Iraqi agency was gradually reintroduced after the holding of elections; however, this perception of Iraqis as being unable to govern themselves has not truly disappeared.

In 2017, it is a slightly different story. Direct colonial occupation, whether at the hands of the British Empire or the United States, is a thing of the past. While there is no doubt that the efforts to wrest control over Mosul from the hands of ISIS are intended to save lives, the language of liberation is still frequently used, even if the intentions are different. Media outlets like CNN, the New York Times and the Washington Post are all guilty of this, with the word “liberation” used by them all. The heinous acts that ISIS commits make this equation of tyrant versus liberation an easy one to make. No one doubts the necessity to remove them from power, or the importance of a strong and cohesive Iraqi state. However, the agency of the Iraqi people seems to come secondary to the establishment of these two goals. In reality, full Iraqi agency is the most effective tool to ensure success on these two fronts.

In order to move forward, these connotations of weakness need to be properly addressed. The turbulent history of Iraq has long been used to justify foreign occupation. The language of colonialism and neo-conservatism is still apparent, even if their presence has been relegated to the history books. These cobwebs need to be dusted off if there is to be any chance of an approach that gives Iraqis agency. For too long Iraqis have been denied these freedoms, all in the name of liberty.

——-

[1] This text is part of a proclamation issued by General Maude upon the liberation of Baghdad, see ʻAṭīyah, G, Iraq, 1908-1921: a socio-political study, p.151

[2] A full transcript of George Bush’s war ultimatum speech from the Cross Hall in the White House. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2003/mar/18/usa.iraq

[3] A full transcript of George Bush’s Mission Accomplished speech http://www.cnn.com/2003/US/05/01/bush.transcript/