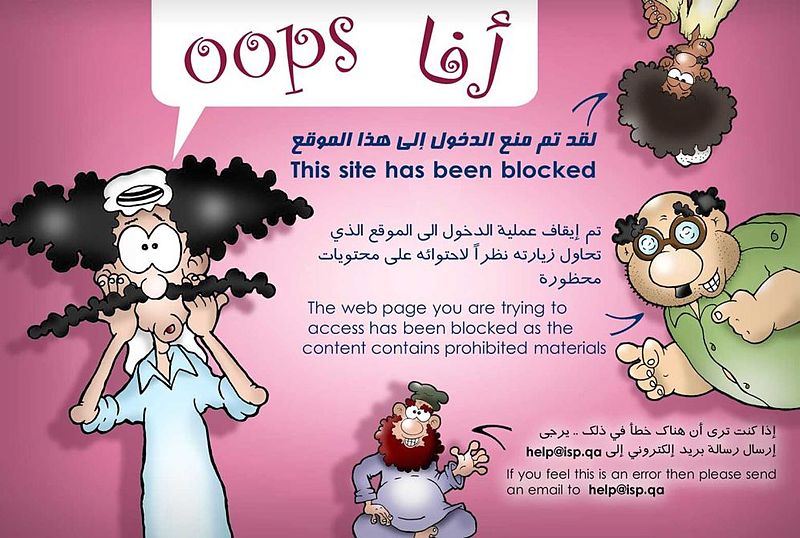

The above image often appears when internet users attempt to access blocked websites in Qatar

For nearly eight years, one of the few sources of meaningful journalism about life inside Qatar – as opposed to the the gas- and oil-rich country’s dealings abroad – has been Doha News. Yet since the close of November, the online site’s articles on cultural, economic, and policy developments have been blocked in the one country they revolve around.

Although Qatar is home to international news network Al Jazeera and even the Doha Center for Media Freedom, the domestic media scene is moribund. Journalism in the handful of Arabic-language newspapers largely consists of barely rewritten press releases, block quotes from government officials, and translated wire reports from the major agencies, even if opinion pages feature occasionally interesting local commentary.

Doha News provided a stark contrast to these platforms. First a news-aggregating Twitter account, then a Tumblr and finally a news site in its own right, the English-language platform has helped numerous expats and Qataris keep abreast of developments within the country since 2009.

Short but engaging articles feature things to do on the weekend, or catch references to the country in the international press. More critical coverage has tackled somewhat controversial topics, such as changes to the country’s migrant labor laws, a fatal fire at a major mall, and the clear potential for overreach under Qatar’s new cybercrime law. Throughout, a slightly tongue-in-cheek style served as a segue to further discussion, marked most clearly by each article’s characteristic sign-off: “Thoughts?”

It was thus a shock to many residents – long used to checking Doha News for updates or arguing on its comment page – to find the site blocked by Qatar’s service providers late on November 30th. Attempts to divert traffic to an alternative domain – doha.news – were soon blocked as well. “[W]e can only conclude that our website has been deliberately targeted and blocked by Qatar authorities,” noted the editorial staff in a statement issued on December 1.

The ultimate causes of the ban remain mysterious, even two months on. The Ministry of Culture and Sports claimed that the closure is a matter of “registration and licensing,” ostensibly due to to the site being officially registered in the United States, not Qatar. Still, this explains little about the timing of the ban: why move to restrict access after nearly eight years of coverage? In a statement provided to the Journal of Middle Eastern Politics and Policy, Doha News editor and co-founder Shabina Khatri noted that Qatari authorities had given no advance notice regarding the move to block the site, arguing that “our legal status was good enough for the authorities until it wasn’t.”

Speculation both within and without the country has focused on two articles featuring Qataris’ personal accounts – one on being gay in Qatar, one criticizing the country’s restrictions on marriages to foreigners – that offended other Qatari citizens’ sensibilities. Both articles fueled long-running criticisms in Arabic that the site constitutes an unwanted foreign influence. This anger has manifested online in the form of Twitter mobs, and almost certainly in personal appeals to government officials. “To the dustbin of history,” clamored the first Arabic response to the site’s closure.

These perspectives ignore considerable efforts by Doha News to serve a broader local community. “Doha News filled a huge gap in the market for accessible local news in English,” noted Alanood Al Thani, a graduate of Northwestern University in Qatar. “The creators of the site [Shabina Khatri and Omar Chatriwala] taught at NUQ’s journalism program, hosting and mentoring many students through the internship program at Doha News.”

It is unclear what might persuade Qatari regulators to again permit full access to Doha News within the country. Numerous requests for comment from the country’s government communications office by JMEPP were not returned, leaving it unclear whether service providers might be compelled to block critical content from other sources in the future. The Doha Center for Media Freedom is satisfied by the government’s official statements, having done its best to avoid the controversy, while a brief spate of international coverage – including by Al Jazeera – has long since faded.

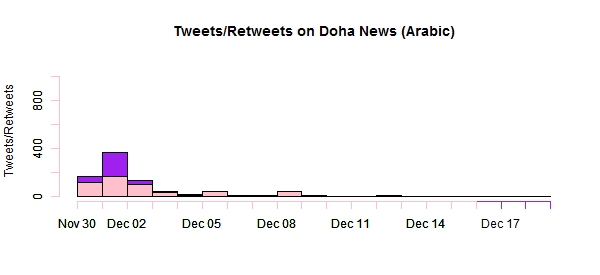

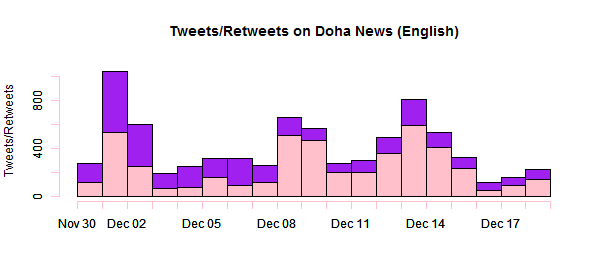

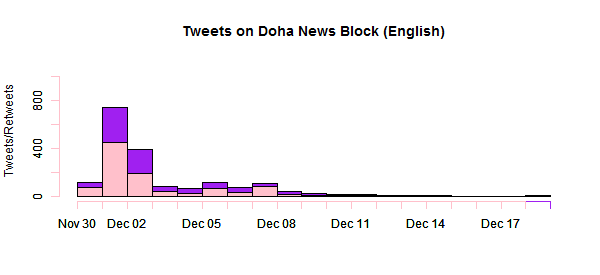

The lack of pressure on Qatari authorities is reflected in online discussions. In the weeks immediately following the site’s closure, initial Arabic Twitter traffic (both original and retweeted) soon faded away to nothing. In English, the closure drove a longer-lasting spike in Twitter discussion, yet references to the closure itself – along with “censorship,” “cybercrimes,” or any combination thereof – quickly diminished as well.

While Qatari officials are, of course, unlikely to describe this as an act of censorship, it fits within a broader pattern of regional governments striving to regulate and repress online dissent and other “troublesome” content. These range from extensive surveillance operations in the United Arab Emirates, as highlighted by the New York Times, to the use of automated “Twitter bots” to harass and overwhelm political discussions regarding Saudi Arabia and Bahrain, as documented by Marc Owen Jones.

For the time being, Doha News continues in an online media limbo. Its main site is blocked within Qatar, but re-posted content is available on Medium. With the Doha News Facebook page and Twitter accounts still available as well, existing users of the site can likely make do, while the site’s capable editors and journalists can no doubt leverage existing contacts to keep coverage going for a time.

Still, if the closure is indeed a response to citizen social pressure, Qatari authorities’ inability to tolerate even mildly critical journalism at home gives further evidence of the tensions between the country’s outwardly cosmopolitan image and a staunchly conservative body politic at home.