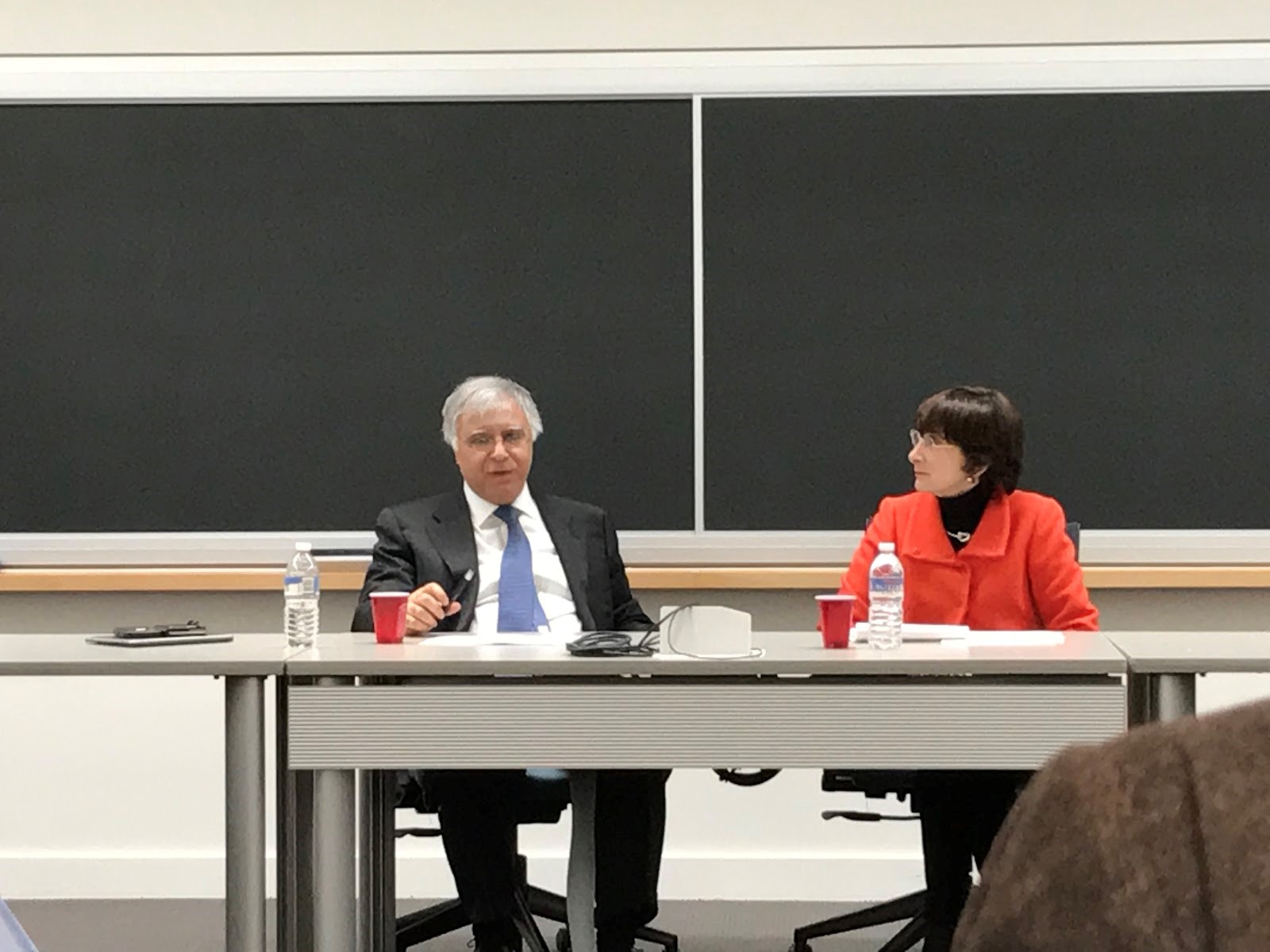

Fareed Yasseen, Iraqi ambassador to the US [Mohamad Saleh/JMEPP]

More than a decade after the disastrous US-led invasion, Iraq remains a nation characterized by uncertainty.

On January 26, the Iraqi ambassador to the US, Fareed Yasseen, gave a talk at Harvard University’s Center for Government and International Studies titled “Iraq: From Dictatorship to What?” A soft-spoken man, Yasseen began his talk by addressing Iraq’s main concern: the war with the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIL). In 2014, ISIL tore through central Syria and Iraq, capturing several important areas including Iraq’s second-largest city, Mosul.

Since then, the Islamic State’s presence in the Middle East has metastasized, and fighters from all over the world have joined the battle. According to Yasseen, Iraqi forces have discovered people of more than 90 nationalities fighting in Iraq alone.

For the past several months, the Iraqi government has waged an offensive to retrieve Mosul from ISIL. “The fighting is going remarkably well,” Yasseen said. And while ISIL will be defeated, he argued, it is just as necessary to address the conditions that led to the group’s expansion before turning to the Herculean task of reconstructing Iraq. To that end, the ambassador discussed three mistakes he believes are at the root of Iraq’s instability today.

‘Criminalizing the military’ and ‘militarizing criminality’

The first misstep mentioned by Yasseen was the US government’s misunderstanding of Iraq’s political climate in the wake of the invasion. The US failed to consider what decades of authoritarian rule did to Iraqis’ views regarding the state. Yasseen referenced Saddam Hussein’s Return to Faith campaign, launched in 1993 amid a period of harsh US sanctions. This campaign, he said, “planted the seeds of extremist religious ideology” in Iraq. Though regime changes by foreign powers often lead to catastrophic results, the inability of the US government to comprehend Iraq’s situation before its invasion of the country was particularly egregious. The ambassador claimed that the original sin of the US was “not finishing the job in 1991” during the Gulf War, though it was unclear whether or not he was being sincere.

The second mistake made was the US decision to occupy Iraq after the fall of Baghdad in April 2003. If the US had established a government in exile before toppling Saddam Hussein, Yasseen argued, many of the oversights made during its occupation may have been avoided. The primary example the ambassador mentioned was the forced dissolution of the Iraqi military immediately following the invasion. As part of US efforts to exert maximum control over the country, over 300,000 armed and trained individuals were dismissed from the military and left without jobs. This naturally led to what the ambassador called “the criminalization of the military and the militarization of criminality.” Former soldiers resorted to criminal activity – both to survive, as well as to accumulate power and influence.

This caused a massive power vacuum, fracturing authority and influence during Iraq’s post-invasion civil war. Of course, the ambassador assumes that Iraqi nationals would have respected a government in exile in a way they did not respect the US government. There is no concrete reason to believe that would have been the case given the fractured nature of Iraqi society – which was, again, a byproduct of the country’s experience with a totalitarian past and the trauma of invasion.

The final mistake Yasseen listed was attributed to the United Nations, when it decided to hold Iraq’s first democratic elections on a model that promoted identity voting. During the elections, Yasseen claimed, nothing was done to teach Iraqis about opposition politics, which did not exist in the country during the Saddam era. The results were to be expected: people voted for names they recognized.

Just as importantly, Sunnis – a favored minority under Saddam’s regime – were discouraged from voting. As a result, they were largely underrepresented in the drafting of the constitution, one reason national reconciliation has not taken place. A different electoral system, one focused on smaller districts for example, may have helped Iraq to sidestep the miasma of corruption and structural weaknesses that characterized the country in the post-invasion period.

Some positive developments?

Yasseen attempted to end on a positive note by listing a few encouraging developments. The first was Iraq’s success in negotiating an 80% reduction of its national debt, a move that will ease economic pressures on a country that already has enough concerns to attend to. The second was Iraq’s new post-Saddam currency, which the ambassador said has worked very well.

Yet the overall tone was pessimistic. At one point, Yasseen jokingly yet revealingly commented: “The fate of Iraq is, we have to have good relations with both the Axis of Evil and the Great Satan.” After close to a decade and a half of bloodshed, invasion, occupation, death, and destruction, Iraq’s geographic location and geopolitical importance all but ensures that it will continue to be a battleground for foreign powers. In response to a question about Iraq’s future position with respect to Russia, the ambassador smiled and threw his hands in the air. He said Iraq is compelled to work with whomever exerts pressure on the region.

Unfortunately, even after ISIL is defeated, Iraq will still be a country in an economically, politically, and morally depressed region. The tenuous positions of its neighbors – a Syria shattered by war, a Turkey that has passed through a failed coup, or a nervous Jordan – does not help. Iran, which was thought to be on its way to a new stability following the lifting of sanctions by the Obama administration, now faces an uncertain future with the Trump administration’s hawkish rhetoric. The Trump administration’s recent decision to ban nationals of seven Muslim-majority countries, including Iraq, only contributes to the pressures faced by Iraq, its government, and its people.

It is up to those in power, whether elected politicians or international organizations, to consider these past missteps as they draw up plans for their future involvement in Iraq. Only in doing so can these mistakes be avoided – which is perhaps, at present, the best that one can hope for.