Iraq’s Popular Mobilization Forces [Photo: Mahmoud Hosseini/Tasnim News]

Since mid-October, the Iraqi Security Forces (ISF) have waged a grueling campaign against the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) to recapture Ninewa Province and its capital, Mosul. As the battle has unfolded, both ISIL and the Iraqi government have intensified their information operations in a bid to shape public perceptions of the fight.

While the media campaigns serve conflicting purposes, they employ similar strategies to influence Iraqis. The first strategy aims to weaken the enemy’s will to resist by instilling a sense of hopelessness and highlighting the battlefield accomplishments of friendly forces. The second touts the benefits provided to Mosul residents by friendly forces while underscoring the enemy’s harmful impacts on civilians. The third strategy attacks the credibility of enemy propaganda by questioning the messenger’s religious legitimacy and the validity of their statements.

The propaganda war for Mosul provides a window into the two sides’ differing organizational priorities, and the political terrain which the Iraqi government must dominate if it hopes to stabilize Ninewa Province. Major combat operations in the Battle for Mosul will likely conclude in the coming months, but the degree to which the current messaging campaigns resonate with Ninewa residents could have significant effects on the Iraqi government’s long-term legitimacy in the region.

The Iraqi media landscape

The propaganda war for Mosul has spanned a wide range of media. In ISIL-controlled territory, residents have severely restricted access to the internet and satellite TV broadcasts. To reach people living in these areas, the Iraqi government has used airplanes to drop millions of propaganda leaflets. Meanwhile, ISIL employs a series of “media points” (“nuqtaat a’alamea,” in Arabic) dispersed among its cities. These small offices screen propaganda and distribute digital and hard-copy content produced by ISIL’s media wings – thus providing a bridge between its vast quantity of cyber propaganda and its digitally isolated citizens.

ISIL reinforces its message through its education system and its members’ proselytizing efforts. It had operated a radio station in Mosul, but a coalition airstrike destroyed the facility two weeks before ISF ground operations began in Ninewa.

The group’s most effective propaganda techniques require it to physically control territory. While Iraqis in recently liberated areas can theoretically access ISIL’s digital propaganda, the organization must compete for their attention in ways that are unnecessary in places under its rule. ISIL’s digital presence is under constant assault, as companies like Facebook (by far the most popular social media platform in Iraq) and Twitter have become increasingly aggressive in identifying and eliminating ISIL-related accounts.

The group must also deal with user-generated obstacles. For example, a Twitter search for #وكالة_اعماق (ISIL’s A’amaq “News Agency”) almost exclusively yields tweets posted by pro-government accounts “hijacking” the popular ISIL hashtag. Furthermore, the government and ISF directly encroach on ISIL’s digital market by employing an extensive array of social media accounts. The Iraqi Special Operations Forces’ Facebook account claims over two million followers; similar accounts exist for many Iraqi military units and political leaders.

The traditional Iraqi media further compounds ISIL’s information disadvantage in areas beyond its control. Iraqi TV stations serve as the primary means by which Iraqis access news, dwarfing all other sources by a wide margin. The most popular news channel in the country, al-Iraqiya, is a government-owned company established following the 2003 US-led invasion. At times the station can seem like a 24/7 anti-ISIL, pro-government infomercial: news reports feature long interviews with Iraqi military officers and unedited speeches by politicians, and the station effectively integrates social media by featuring popular government slogans. The hashtag #قادمون_يا_نينوى (“We are coming for you, Ninewa,” the official name of the ongoing Iraqi military operation) often appears in graphics during the station’s broadcasts.

Figure 1: Two images from al-Iraqiya News highlight the government’s ability to integrate social media into traditional platforms. On the left, Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi announces the beginning of military operations in Ninewa, with the hashtag “our borders are the borders of Iraq” in the top left corner. “#We_Are_Coming_For_You_Ninewa,” the official name for the Iraqi military operation to retake Mosul, appears in the second image. Both reports show government attempts to portray Abadi as a strong military leader.

The Iraqi Media Network (IMN), the holding company that owns al-Iraqiya, also includes local TV affiliates and radio stations. Among IMN’s affiliates, Mosul’s al-Mawsleya has produced the most widely used footage of the ongoing battle, and frequently airs reports from correspondents embedded with ISF.

Unsurprisingly, though, the fact that IMN outlets tend to serve as mouthpieces for the government has made them less popular and less trusted in predominantly Sunni areas of Iraq. Many in these regions favor al-Sharqiya TV instead, an independent outlet more critical of the government.

The rhetoric of certain victory

Iraqi Prime Minister Dr. Haider al-Abadi announced that the campaign for Ninewa had begun in earnest on October 16, 2016, telling the Iraqi people in a televised speech that “the hour of victory has rung … I announce today the beginning of this heroic operation to liberate you … God willing, we will soon meet in Mosul and celebrate your freedom and salvation.”

As Abadi continued his speech, he emphasized a theme his government has used extensively in its messaging campaign: the Iraqi military is an unstoppable force. ISIL’s inevitable defeat in Mosul will follow the same template of ISF success established in Fallujah, Ramadi, and various other Iraqi cities.

In the weeks preceding Abadi’s speech, the Iraqi Air Force dropped approximately 17 million leaflets over Ninewa conveying the same message. One of the pamphlets, entitled “The Hour of Decisiveness in Mosul,” lists Iraqi cities and the dates of their liberation along with a clock, indicating that Mosul’s time is fast approaching. The leaflet proclaims: “The Iraqi forces continue to liberate your cities and crush the takfiri [those who excommunicate other Muslims] gangs.”

The leaflets dropped at the start of the Mosul campaign took a more ominous tone, instructing Iraqis that “Da’esh [the Arabic acronym for ISIL] has ended and will never return … for those among you who want mercy and pardons, it is up to you to capture any Da’esh member, whether Arab or foreigner, and to present him to security forces.”

Figure 2: “The Hour of Decisiveness in Mosul” – Pamphlets dropped in September 2016 throughout Ninewa Province list recent ISF victories over ISIL to portray the inevitability of government victory in Mosul. Source: iraqnewspaper.net

Highlighting battlefield success

Both sides have also attempted to convince Iraqis of their prowess by distributing estimates of enemy soldiers killed and equipment destroyed. ISIL has produced a weekly infographic of its oft-inflated claims, while the Popular Mobilization Front – a government-sanctioned body of mostly Shia militias fighting against ISIL – has released a similarly formatted response. These infographics can prove particularly effective in shaping traditional media coverage: because accurate casualty figures are notoriously difficult to obtain, the government faces continual pressure to refute ISIL’s claims.

Figure 3: On the left, an ISIL infographic outlines battle damage assessment claims for the third week of the battle of Mosul. On the right, a PMF infographic lists the number of square kilometers liberated, villages freed, car bombs disabled, and ISIL fighters it claims to have killed. Sources: academic archive run by Harvard Belfer Center Research Fellow Christopher Anzalone (ISIL infographic); infographic archives on PMF website, available at al-hashed.net (PMF infographic).

While body counts can shape the contours of the Mosul narrative, few forms of media more dramatically affect news coverage than pictures and videos from the front lines. Both pro- and anti-ISIL media outlets place a premium on producing footage that simultaneously shows the greatness of their victories and the totality of their enemy’s defeat.

As Iraqi forces have advanced through eastern Mosul, they have seized upon opportunities to tout their control over identifiable landmarks. After capturing the Great Mosque of Mosul, one of the more distinctive features of the city’s skyline, the ISF trumpeted its success on social media accounts and conducted a series of media interviews on the grounds of the mosque. The victory held a particularly symbolic importance given ISIL’s use of the mosque as the backdrop for some of its more gruesome videos. The ISF took a similar approach upon taking control of Mosul University, the Mosque of the Prophet Yunus (Jonah), the ancient ruins of Ninewa, and Saddam Hussein’s former presidential palace.

Figure 4: Facebook posts by the Iraqi Counterterrorism Service (ICTS) show their soldiers in control of the Grand Mosque of Mosul (left) and Saddam Hussein’s former presidential palace. The soldiers in the bottom-right picture are holding a captured ISIL flag upside-down, a common pose on ISF media. Source: ICTS’ Facebook page. ICTS is an Iraqi special operations unit that has been instrumental in the battle for Mosul.

Both sides, and especially ISIL, also like to document the more grisly aspects of the conflict. Pictures of corpses are commonplace in ISIL propaganda, but are also propagated by the Popular Mobilization Forces and even mainstream TV stations. Captured fighters and equipment often figure prominently in videos, reinforcing claims of battlefield success. ISIL has also recently released a series of videos promoting its use of drones in fatal attacks on Iraqi forces.

Figure 5: In a video released by the ISIL’s A’amaq “News Agency” on November 6, 2016, an ISIL fighter posed in front of a convoy of destroyed Iraqi government military vehicles in eastern Mosul’s Aden District. The wreckage is likely the result of an ISIL ambush captured by CNN’s Arwa Damon and Brice Laine. Iraqi forces currently control the entirety of the district.

The competition for civilian support

Both sides also recognize the need to bolster their support among Ninewa residents. In that effort, ISIL has shrewdly exploited Iraqi grievances against the government. Reports on the refugee situation in northern Iraq have proven fertile ground for propaganda which highlights government ineffectiveness. In a December 2016 broadcast from a refugee camp on the border between Iraqi Kurdistan and Ninewa Province, al-Sharqiya News interviewed dozens of refugees living in deplorable conditions. Standing in the ruins of a burned-down tent, former Mosul residents complained bitterly about shortages of benzene and gas, all while laying the crisis at the feet of the Kurdish and Iraqi provincial authorities.

These images provided a stark contrast with a video released by ISIL in late November which purported to show the idyllic life in southeastern Mosul’s Sommar District. One resident standing in front of a seemingly thriving market boasted that “there is produce, there is gas, there is benzene, it’s all here. Everyone from the Army offers nothing, well by God, here is something … here is bread, sugar, the livelihood of Sommar.” After the merchant’s bold proclamations, the video cuts to a Potemkin supermarket packed with meticulously organized groceries.

The life depicted in the video is undoubtedly staged. In fact, one of the key reasons for ISIL’s unpopularity is its profound ineptitude in managing local economies and providing public goods. Nevertheless, these videos may appeal to some desperate Iraqis, and artificially inflate expectations that the Iraqi government should meet the same standards portrayed by ISIL’s works of fiction.

Figure 6: ISIL propaganda (right) attempts to portray an idyllic life for civilians under its rule in Mosul, providing a stark contrast with conditions in local refugee camps. The text of the al-Sharqiya broadcast (left) asks, “What is the reason behind the burning of Camp Khazr?” Source: screenshot of al-Sharqiya News live broadcast from Camp Khazr.

In addition to burnishing its own image, ISIL also highlights the negative impacts of coalition actions on Mosul residents. A December 7 ISIL video, narrated by abducted British journalist John Cantlie, criticized coalition airstrikes that targeted the five bridges spanning the Tigris River in Mosul. The bridges — which government officials have promised to rebuild — were destroyed to stem the tide of vehicle-borne suicide bombers and ISIL reinforcements pouring into eastern Mosul.

The video then shows a series of interviews with Mosul residents, who blame the coalition for a range of issues including water, electricity, and fuel shortages. ISIL also makes allegations of wanton coalition attacks, typified by a publication in an-Naba Magazine alleging the use of controversial white phosphorus munitions in Mosul (US forces have used white phosphorous for the limited, permissible purposes of marking and screening in unpopulated areas on the outskirts of the city). Given the daunting task of rebuilding Mosul after ISIL’s defeat, the organization could remain resilient if it can pin economic hardships or perceived injustices on the government.

The Iraqi government combats these claims by highlighting the benefits it says their forces are providing for citizens in formerly ISIL-held areas. Nuwfil Hamadi al-Sultan, the provincial governor of Ninewa, has led the local campaign, touring recently secured factories and promising that the jobs they once provided will soon return. Embedded reporters from al-Mawsleya frequently interview residents in liberated areas, who invariably curse ISIL and extol the virtues of the Iraqi army. A report broadcast on January 18, and subsequently posted on YouTube, featured an exchange between a reporter and a young girl holding hand-made Iraqi flags (beginning at 11:34):

Reporter: “How was Da’ash for you?”

Girl: “They were very harsh.”

…

Reporter: “Is that a flag of Iraq, do you love Iraq?”

Girl: “Yes!”

Reporter: “Do you love Da’esh or Iraq?”

Girl: “Iraq.”

Reporter: “Good for you. How do you see the Army?”

Girl: “Very good with me.”

Reporter: “Do you have anything to say for the Army?”

Girl: “I love you. Peace be upon you and protect you.”

A similar al-Mawsleya TV report from November shows troops with the Counter Terrorism Service (CTS), an Iraqi special operations unit, advancing as civilians celebrate, shower them with candy, and kiss them. In a more interactive effort, the government launched a campaign in December called “Letters to Mosul,” which encouraged Iraqis to submit handwritten messages of support for Mosul residents. The Iraqi Air Force then used their aircraft to drop the letters over the city.

The government has also sought to distinguish its treatment of civilians from previous campaigns, like Fallujah, where PMF units faced accusations of human rights abuses. Its claims appear legitimate, as both US commanders and UN observers have praised CTS’ conduct in Mosul. ISF have accepted extreme tactical risks to avoid causing civilian casualties, frequently treat wounded civilians on the battlefield, and use local radio stations to broadcast potentially life-saving warnings in advance of major operations. By doing so, the Iraqi military hopes to avoid creating more anti-government grievances and convince locals that they are a liberating, rather than conquering, force.

Figure 7: “Letters to Mosul”: In a post by Twitter user HewarMaftuh (“Open Dialogue”), a video shows Iraqis submitting encouraging letters meant for the residents of Mosul. The post also contains a hashtag referencing ISIL’s “A’amaq News Agency,” a technique meant to “hijack” a pro-ISIL Twitter search. On the right, an Iraqi Air Force video depicts the air drop of “letters from every province of Iraq to our people in Mosul.” Both posts use the hashtag “Letters to Mosul.”

The credibility battle

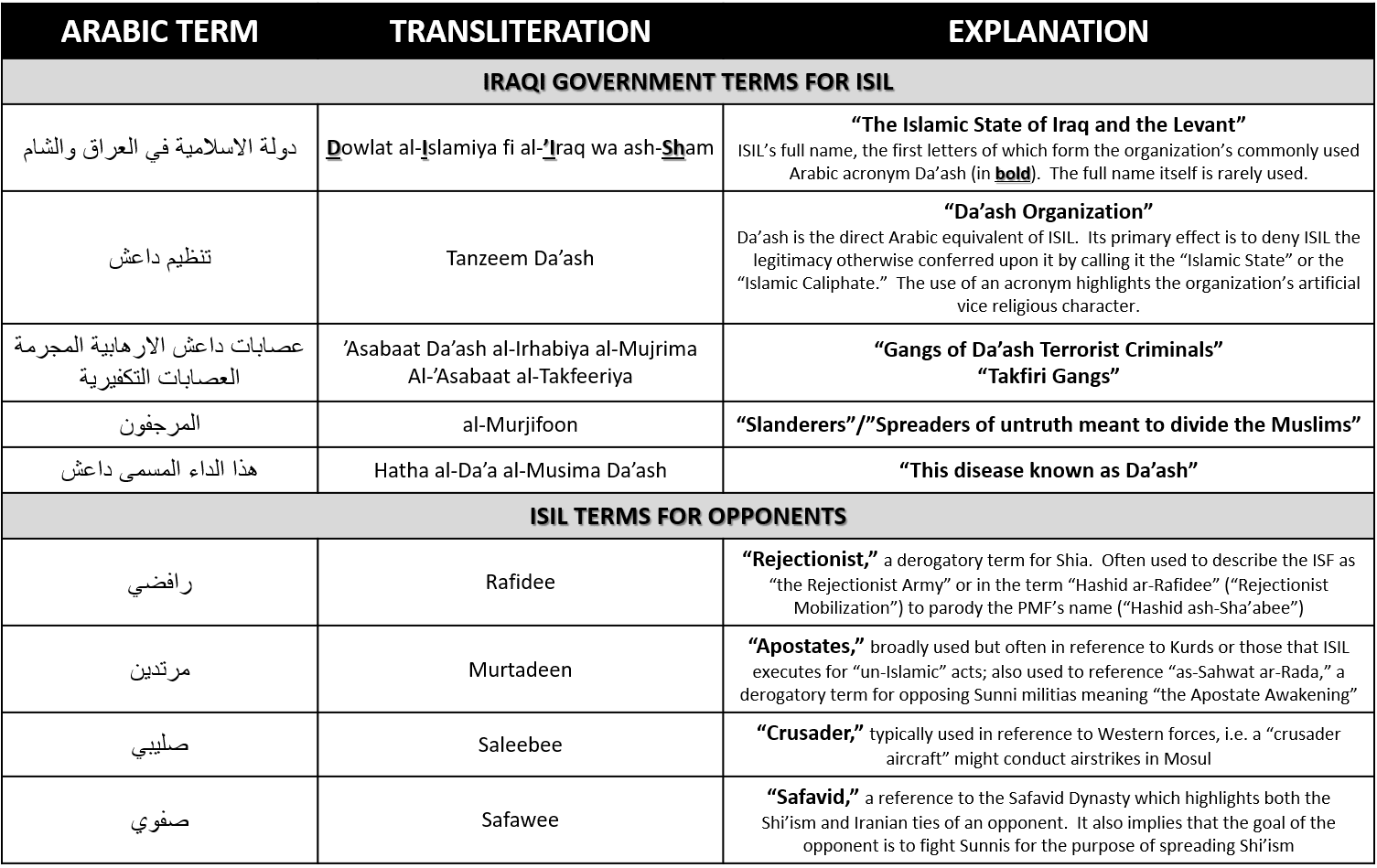

The final line of effort in the propaganda battle for Mosul targets the credibility of enemy messengers and statements. The delegitimization strategy begins with basic linguistic decisions regarding what to call the enemy. Rather than confer legitimacy on ISIL by acceding to grandiose titles like the “Islamic Caliphate,” the government highlights the group’s outlaw status by referring to them as “criminal terrorist gangs.” The government also refers to the group as “Da’esh,” the Arabic equivalent of the ISIL acronym. Although the term itself does not hold any meaning and is not inherently insulting, its use denies ISIL the religious and historical legitimacy that a name like the “Islamic State” seeks to assert.

The government builds on the theme of religious illegitimacy by publicizing ISIL’s deviations from its supposedly pious beliefs, typified in a recent Counter Terrorism Service Twitter post that displayed liquor bottles found following a raid on an ISIL position in Mosul. The government and Popular Mobilization Forces also levy frequent accusations of “Wahhabi” or, more explicitly, “Saudi” influence among ISIL members.

For its part, ISIL uses terms that attack the religious credentials of the government, often in sectarian fashion. The term “rafidee” (“rejectionist”), typically used to describe the Iraqi Army and PMF, stems from ISIL’s claims that Shia Muslims reject three of the caliphs who succeeded the Prophet Mohammad, whom Sunni Muslims regard as legitimate. The labels “apostate” and “Safavid” similarly assert that the government’s forces are composed of religious deviants and Iranian agents.

Figure 8: Key vocabulary used by ISIL and the government to delegitimize each other

While linguistic choices attempt to broadly delegitimize the enemy, some propaganda attempts to catch its target in a “lie” underscoring the opposition’s supposed efforts to deceive their Iraqi audience. In early December, the 9th Iraqi Army Division captured al-Salaam Hospital in eastern Mosul. Iraqi officers subsequently touted the event on al-Sharqiya TV, boasting that they had “freed a strategic hospital.”

But shortly afterwards, the soldiers were forced to withdraw in the face of a withering ISIL counterattack that included at least six suicide car bombs. Following US airstrikes, Iraqi forces have since retaken the hospital. Despite the government’s later victory, ISIL seized on the initial withdrawal as an opportunity to cast doubt on the Iraqi government’s claims of progress. ISIL produced a series of videos which posed a troubling question for Iraqis: if the government’s fight was advancing so smoothly, why were ISIL fighters celebrating among burned-out tank hulls at the site of a “strategic” ISF victory?

Another video showed a (likely coerced) account of the battle from a captured Iraqi corporal. The young soldier described the scene as an utter defeat for his unit: waves of suicide bombers, destroyed vehicles, officers killed, his unit left in disarray. The videos build on a theme: do not trust the government or “rumors”; the military lies about its strength and its accomplishments.

Who’s winning?

Given the government’s dominance of traditional media and its parity, at a minimum, in social media, its message almost certainly reaches a greater percentage of the population than ISIL’s. The government also has a significant advantage in the product it is selling: it will almost certainly retake Mosul in the coming months. As its advance continues, the ground-level reality will continue to bolster the government’s credibility rather than ISIL’s. In the short run, these factors should allow the government to effectively shape the narrative surrounding the battle for Mosul.

But the effects of ISIL’s propaganda could linger. The success of reconstruction efforts in post-battle Mosul remains far from certain. In smaller cities like Fallujah and Ramadi, the government has proven capable of “clearing and holding,” but far less adept at rebuilding. ISIL propaganda may not succeed in mobilizing large numbers of supporters to defend Mosul, but it may contribute to the erosion of public trust in the government, especially if economic or security problems persist after ISIL’s expulsion.

The anti-government grievances highlighted in ISIL’s propaganda will almost certainly outlive the organization in its current form; its ability to identify and co-opt issues that resonate with Iraqi Sunni communities may continue to fuel conflict and shape the next generation of an organization that has repeatedly reconstituted and rebranded itself over the last 14 years.

However, as the ongoing battle for Mosul demonstrates, highlighting indisputable facts remains the most effective technique for countering ISIL’s information operations. Few Iraqis will believe ISIL claims of success in Mosul when the Iraqi flag flies atop every landmark. As the ISF continue to make gains, analysts have already pointed to the declining volume and coherence of ISIL’s propaganda, as well as its pre-emptive framing of defeat in Mosul.

Similarly, the Iraqis can render hollow ISIL’s accusations of governance failures by successfully addressing those legitimate concerns. Unfortunately, accomplishing that task is incredibly challenging; if it were easy, the government presumably would have prevented ISIL’s rise to prominence from the onset. The difficulty of providing governance that meets local expectations means that the effects of the propaganda battle for Mosul will likely endure long after the government has freed the city from ISIL control.