BY ROBERT REYNOLDS

In 1840, Abraham Lincoln authored a plan for the Whig party to win the upcoming election: “watch on the doubtful voters, and from time to time have them talked to by those in whom they have the most confidence.”

Democrats need a similar plan today. If liberals and conservatives voted at the same rates, Hillary Clinton would be president, Democrats would have a Senate majority, and Merrick Garland would be on the Supreme Court. But, because today’s nonvoters lean liberal, America’s right wing controls every branch of our government.

After last November’s election, many Democrats believed Trump’s presidency would motivate our “doubtful voters” to the polls. Yet, Democrats have lost all four congressional special elections this year.

As a behavioral science researcher, the insufficient change in liberals’ voting behavior is not surprising. One of my field’s most robust findings is that even with high motivation, we are often immune to change—even when our life is at stake. Harvard behavioral scientists report, “when doctors tell heart patients they will die if they don’t change their habits, only one in seven will be able to follow through.”

Instead of aiming to motivate with consequences, research suggests voters may be most motivated by social influence. A 2010 study found that Facebook users shown photos of friends who voted were more likely to vote, leading to an additional 340,000 votes that year.

The 2012 Obama campaign built on this finding and saw a statistically significant increase in voter turnout when it asked supporters to share online content with their Facebook friends. Most recently, the 2016 Clinton campaign created a tool for supporters that would analyze their Facebook friends and produce targeted text messages for the supporter to send specific friends. While social influence voting nudges are now a common presidential campaign tactic, they remain rare in lower-budget congressional races.

So how can Democrats employ the lessons of behavioral science in 2018? With the help of Trump-resisting friends, I recently developed and user tested a low-tech social influence tactic that congressional campaigns can cheaply scale. Ahead of Montana’s U.S. House special election on May 25th and Virginia’s gubernatorial primary on June 16th, we recruited 60 Montanans and 24 Virginians to complete an online pledge stating: (i) their name, (ii) their cell phone number, and (iii) the name of three friends they would hold accountable to vote.

Two days before the elections, we texted registrants asking what time they planned to vote and reminding them of the three friends they pledged to get to vote.

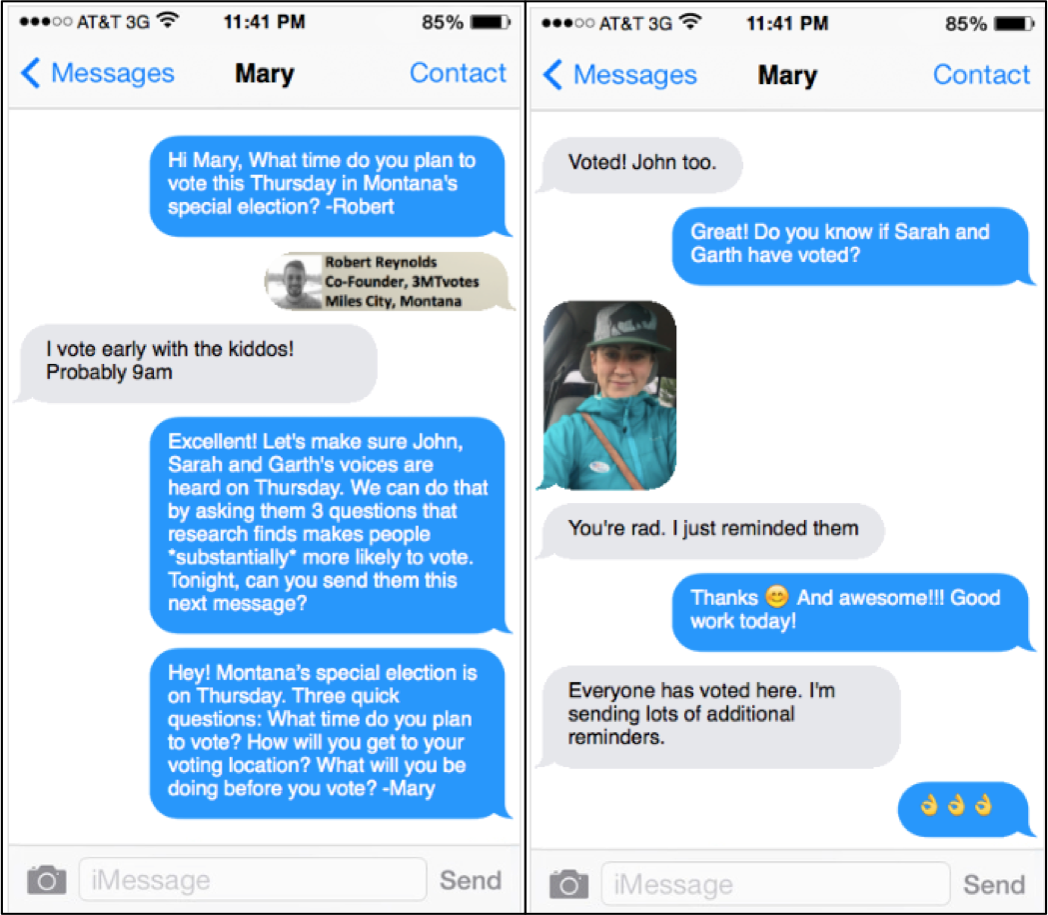

In both states, 67 percent of the registrants responded to our messages, and over half of those who responded confirmed that they reached out to their friends. Responses included, “I got 4 who have already or will vote” and “I brought my dad, sister, and brother-in-law!” In gratitude for the virtual pat on the back our messages embodied, one person sent us a selfie with her “I voted” sticker and the message, “You’re rad.”

Sample text message conversation from first pilot test

While a randomized controlled trial was not used to measure the change in turnout caused by these pilot tests, the high response rate is promising. In a 2016 election study, a text message intervention with only a 3.5 percent response rate was found to produce a statistically significant increase in turnout.

As a next step, Democrats should utilize the early 2018 special elections in South Carolina and Florida to test this low-cost tactic’s impact on turnout of the registrant and their three friends. Then, informed by the findings of this randomized controlled trial, this design can be iterated and improved in time to be scaled across the November congressional elections.

Democrats have the numbers. But to win elections, we must turn more supporters into voters. In 2018, campaigns can do this by utilizing phone banks, canvasses, rallies, emails, and social media to garner pledges from supporters to get their friends to vote. In close races, Lincoln’s 177-year-old strategy could make all the difference.

The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the view of any organization he is affiliated with.”

Photo Credit: Stephen Velasco via Flickr

Edited by Kimberly Howard