Source: http://www.lsbf.org.uk/blog/news/emerging-markets/ghana-turns-imf-bailout-financial-crisis/2562

Ghana Rising

Among the emerging Africa narratives, Ghana has often been touted as something of a model: over a decade of consolidated democratic institutions, economic expansion, and poverty reduction. With economic growth of over 6% for the past seven years, buoyed by high commodity prices, Ghana appeared to have avoided many of the pitfalls in macroeconomic management that afflicted other countries on the continent. When the Kufuor government discovered oil in 2007, experts believed that Ghana would use the newfound wealth wisely and avoid the economic and political malaise that had plagued many oil-exporting nations in the region.

The discovery of oil coincided with a much-celebrated public debt issue, only the third in Sub-Saharan Africa since the debt relief programs of the early 2000s. The promise of future oil and the issue of sovereign debt led to large capital inflows in both the banking sector and FDI. Access to international finance can help a small, import-dependent economy like Ghana undertake the necessary capital investments to develop the oil sector. How, then, did Ghana end up seven years later with the world’s worst performing currency and a full-blown economic crisis?

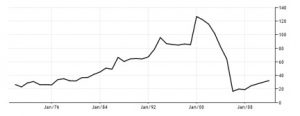

Figure 1: External Debt Stocks as a % of GNI, 1967-2012; A repeat of history?

The Anatomy of a Crisis

Instead of investing in infrastructure, public goods, and job creation, successive governments diverted the newfound finance into the pockets of civil servants. The public sector wage bill grew to 70% of the budget in 2012. A cynical reading might interpret this government-spending boom as a reelection ploy for the Atta Mills-Mahama government. But regardless of the political economy, most of the spending went directly into consumption instead of investment and imports grew rapidly.

Spending also created inflationary pressures in the booming economy, flush with international capital and expectations of oil riches. As prices rose, the currency began to appreciate in real terms while remaining nominally stable because of capital inflows. The ingredients of a crisis—procyclical spending, large deficits, short-term debt, high inflation, and overvaluation—were all there. But policymakers ignored these early warning signs, perhaps overconfident that Ghana had left the past behind.

Then, in 2013, the price of gold collapsed and Ghanaian exports lost significant value. With the terms of trade deteriorating quickly, the current account ballooned to 12.3% of GDP. The fiscal deficit also worsened, as government coffers lost revenues from export tariffs on gold. Today, the budget deficit stands at 10% of GDP. At the same time, markets reacted to news of potential monetary tightening by the Federal Reserve by pulling out of emerging markets (the so-called “taper tantrum”), putting increasing pressure on the exchange rate.

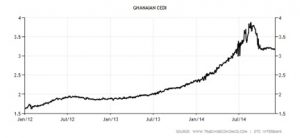

In the past year, it appears that Ghana’s twin deficits have resulted in a full-blown currency crisis. Over the course of 2014 the cedi lost 40% of its value, rebounding only after Ghana entered bailout talks with the IMF in August. Overspending and a widening trade deficit had put Ghana in a precarious position. Over fears that the twin deficits were unsustainable, international investors pulled out, increasing the pressure on the currency. Rising import prices have exacerbated inflation, which stood at 16.5% in 2013. And to the extent that external debt is denominated in foreign currency, the balance sheet effect has increased the government’s debt service substantially, as more cedis of revenue are required to service the same dollar debts.

Figure 2: The cedi in free-fall, Q1 2012-Q3 2014

Note: This graph displays the GH₵/$ spot rate, so an increase represents a depreciation, or a loss in value.

The Bitter Medicine of Austerity

Though the cedi seems to have stabilized, it will remain weak as long as the current account is in deficit. This means that households will feel the pinch in their loss of purchasing power. The government has moved to cut spending and tighten monetary policy in hopes of stemming capital outflows, controlling inflation, and reducing import spending. However, higher interest rates make government debt harder to service, worsening fiscal problems. And with the central bank rate already at 21%, it seems unlikely that additional increases will keep capital in the country.

The IMF will undoubtedly require a combination of belt tightening, wage freezes, and structural reform in return for an $800 million credit. All of these policies will result in a loss of output, with ordinary households bearing the brunt. The IMF has already downgraded Ghana’s growth to 4.8% in 2015. However, stabilization is essential for long-term growth. In the future, something akin to a structural budget rule might be useful for avoiding a repeat of this scenario. The government must institutionally commit to spending only primary tax revenues during good times and saving commodity income for the bad times, rather than exacerbating the booms and busts with pro-cyclical spending.

What the crisis reveals are the weaknesses in Ghana’s public finances, and the dangers of external debt with weak public institutions, particularly when oil revenues enter the equation. Ghana has not fully shed its checkered macroeconomic past, and must wade carefully into the waters of financial globalization. Ghana will need stronger management if it is to fulfill its promise as a destination for investment, and more importantly, as a model for the continent.