How did Buhari win? Or, as the opposing camp have asked, how did Atiku lose? This article considers pertinent forces that shaped the election outcome, and argues that technological infrastructure already found in Nigeria holds promising solutions for future elections.

Africa’s largest democracy went to the polls to elect a president on the last Saturday of February. If you placed one finger on the Nigerian pulse before that weekend, a vital sign came from the country’s biggest music star. Davido arrived in Nigeria from a sold-out performance at London’s O2 arena in January, and shared a post to his nine million Instagram followers:

“Buhari had four years to work just to be re-elected (and) he did nothing. But fellow Nigerians think he’ll work hard for the next four years where he won’t be contesting for re-election (and) has nothing to lose. Please use your brain.”

Davido revealed the truth about Nigeria, particularly for the 2019 presidential election. Mention “Buhari” and Nigerians split into two almost perfectly divided camps:

One is unwavering in its loyalty to the president. They consider his critics as mean-spirited: they argue Buhari’s policies will yield long-term results if everyone is patient, and insist a clean-up is underway to fix a broken system he inherited. The opposing camp is adamant that Buhari has presided over a surge in extreme poverty to the point where Nigeria now ranks worse than India. They pointed to Nigeria’s slow-moving economy and resolved to vote for business-friendly change, promised by Atiku Abubakar, fast-moving reformer and Buhari’s opponent.

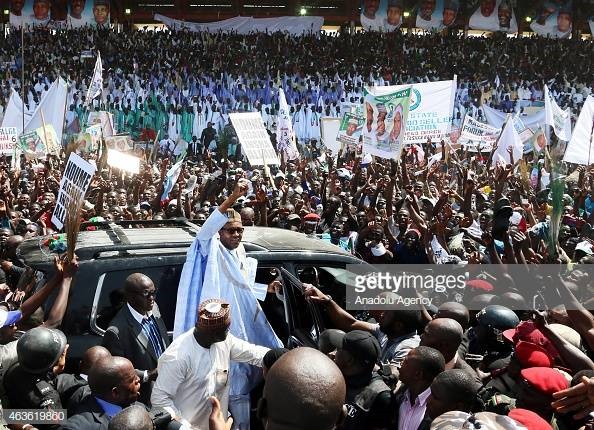

From Nollywood stars to clergymen, Instagram and Twitter were flooded with confident posts from the Atiku’s change camp, convinced victory was afoot in the build-up to election day. Even Nigeria’s king-maker in every presidential election – with this recent exception – former president Obasanjo, endorsed Atiku – his former vice president. Meanwhile, at Buhari’s final rally with his vice-president in a battleground state, the party’s chief ended up being stoned, prompting an ominous security escort from the stage. The capital’s Aso Rock Villa appeared ready for a change of guards.

In this context, how did Buhari win, or rather how did Atiku lose?

Operational Failures

Maria Arena, head of the EU’s election observation mission to Nigeria, admonished the postponement of the election by one week, five hours before polls opened. Highlighting the election commission’s “operational failures”, she observed that the late opening of polling units on voting day and the lack of public information resulted in “confusion, some tensions, and people disenfranchised from voting”.

In Buhari’s first term, the commission struggled with smaller-scale elections, frequently declaring “inconclusive” results. In a stroke of uncharacteristic certainty, the commission’s declaration of fifteen million nationwide votes for Buhari over Atiku’s eleven million marked a quantum leap in their performance. Barely two weeks later, in early March, the commission reverted back to its pattern of declaring inconclusive results for smaller scale governorship elections.

Voting Irregularities

Nigerians on WhatsApp have seen a kaleidoscope of disturbing videos showing ballot papers set ablaze, destroyed with water or torn-up in unlawful acts of sabotage. In some, badge-wearing individuals are stamping ballot papers repeatedly, in favour of one party listed at the top-right corner. In regions Atiku banked on, thousands of voters’ cards were not “accredited” by the card-readers, resulting in voters being turned away.

Pledging to contest his defeat in court, Atiku argues there are “statistical impossibilities” in the results announced in some states. Lagos, the commercial capital of twenty million, reportedly only turned out one million voters. Buhari took over half of them. In a devastated Borno State, the stronghold of the world’s most deadly terrorist sect, Boko Haram, Buhari is claimed to have gained nearly twice the number of votes that he secured in Nigeria’s megacity – despite explosions in Borno on election day.

“I have colleagues with four wives and nineteen children based in northern villages. These men go up to join their families during elections,” said a senior anti-corruption Nigerian civil servant, off-record. “Nigerians who never leave the south won’t believe how populated the north is becoming.”

Contradicting Buhari’s alleged popularity in Lagos, Nigerian Stock Markets crashed, losing a gargantuan 85 billion naira ($233 million) when polls showed the president’s lead over investor-favorite Atiku.

Identity Intersections

Populated with Buhari worshippers, the majority of Nigeria’s north could not subscribe to the Atiku brand and their perceptions of its corruption. Atiku also centred his campaign on a premise that many northerners fear: “restructuring”. The promise to redesign Nigeria’s federal structure of prebendalism. Atiku’s risky wager to deliver a refurbished Nigeria was heralded with applause in the south while his northern home region stood famously averse to radical architectural change.

Nigeria’s north has mastered the politics of collecting voters’ cards, rallying behind their “chosen candidate” and voting en masse. The south, more invested in commercial ventures and social media analysis, are once again left tamed by the democracy chess masters.

Wrestling Modernity

Tasked with Africa’s greatest logistical exercise, Nigeria’s election commission work under byzantine instructions. When polling centres close, officials keep ballot boxes in opaque locations overnight. Come morning, before microphones and television audiences, an official narrates results for over 70 political parties, one state at a time. Citizens vote on Saturday; the system names a winner by Wednesday.

“The only way to believe in the process is with a dose of dark optimism. It cannot get any worse.” says Ifeoma Aleke, a member of Nigeria’s 67 million youth initiative.

Estonia’s internet voting system allows citizens to stay home and vote on a computer. Ballots are encrypted so incoming governments cannot see individual choices. To address hacking risks, voters switch over to a phone device to verify their submission got to the authorities.

Nigeria’s mobile sector is famously lucrative, with penetration rates at 84% of the population. Averse to the risk of newsworthy fines telecom providers vigilantly register all Nigerian phone users with their biometric information. Already living in the digital age, Nigerians are well placed to take voting online for future ballots.

Like charged grenades, Nigeria’s leadership have historically averted calls to digitise the voting process with live results. While resigned to the status-quo, citizens increasingly admit e-voting could reduce the chances for manipulating results.

At the end of March, Nigeria’s Court of Appeal started hearing Atiku’s petition to be declared winner of the election – or at a minimum – to have a fresh election ordered. Putting aside potential outcomes, Buhari appears to have shaken off two prolonged, bed-resting illnesses in London, but four more years leading a divided electorate will not likely be a hero’s ride into the sunset.

Toby Chidolue has a background in architecture and project management after studying at the University of Nigeria and Ryerson University respectively. He has since worked on large construction and government contracts in Nigeria, and in sales and logistics in Canada for companies like CBC and Kraft Heinz. He is involved in grassroots politics in Nigeria.

Daniel Akinmade Emejulu studied at SOAS, Duke University, The Hague Academy of International Law and The Graduate Institute Geneva. In the last 6 years, he has worked for international organizations in Geneva, Switzerland and written for The Financial Times and The Economist Intelligence Unit, Huffington Post and Monocle, among others. He is a qualified lawyer in Nigeria.