The average person can turn on the nightly news any day and see stories of terrifying acts—and clear crimes—ranging from the bombing of children in Syria to the massacre of Tamils in Sri Lanka. But if one were to refer only to the cases brought by the International Criminal Court (ICC), they would be left with the distinct impression that atrocities are confined to Africa.

Since the ICC’s founding in 2002, the Court has opened investigations involving nine countries, eight of which in Africa. While the Court has opened preliminary examinations in a wider range of countries from Afghanistan to Colombia, for some African countries it has been too little, too late. An African exodus from the Court, led by Burundi, South Africa and Gabon, seems imminent, and rightly so. At least, when African nations are no longer members of the ICC, the referral of alleged crimes will be more clearly seen on the world-stage as the political maneuver that it is.

The ICC has demonstrated in its decade of operation that it is not, in fact, an institution of justice, but rather an instrument of politics. Powers like the U.S. and Russia, are not parties to the Rome Statute, but have veto power for any U.N. Security Council referral—making them, and even their allies, completely immune to ICC jurisdiction. Politics have already thwarted a referral of Syria. African countries may be ‘brought to justice’ by those that are themselves immune to ‘justice.’ Even if that could be considered fair, the question remains: is it helpful?

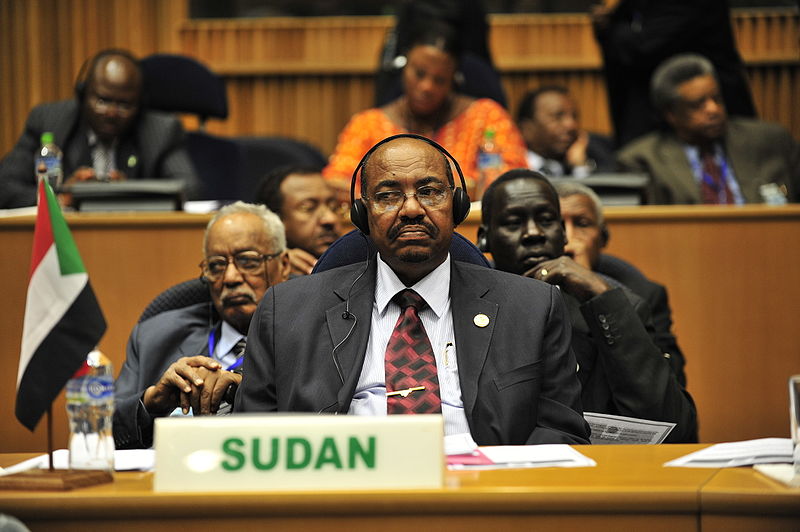

Not to those Africans whose autonomy would be usurped by the ICC. The Court has attempted to prosecute sitting presidents of African countries, even when a conviction would inevitably mean a change in regime. The ICC’s attempt to force South Africa to arrest Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir while he visited during an African Union meeting put South Africa and the ICC, instead of the people of Sudan, in the position to decide who would lead Sudan.

The ICC insisted that justice was not being served by South Africa, which refused to arrest al-Bashir. However, a lesson in justice from a Court that has spent over $1 billion dollars to convict four people over 14 years is lost. South Africa recognized the danger to African autonomy that arresting Bashir posed. The world must recognize that a billion dollars would have been better spent helping to alleviate the conditions on the continent that led to the rise of tyrants rather than imprisoning four people. ICC convictions have been more symbolic than impactful, but Africa does not need symbolism. Africa, at long last, needs self-determination—which is not found in the Rome Statute. The avenue on which African countries should focus their judicial power is the African Court of Justice and Human Rights. While this Court may be promoted for nefarious reasons by President Uhuru Kenyatta of Kenya (who has been investigated by the ICC), it offers the prosecuting authority that the world wants as well as the self-determination that Africa needs.