BY YAEL STERN AND GAL LIN

“Will you answer a survey we are conducting to understand people’s values?” the surveyor asked the young Iranian man on the other end of the phone line. “Sure,” he answered. The young man answered the surveyor’s questions pleasantly and openly, even joking occasionally. They reached question twenty: How similar are you to someone for whom tradition is important? Suddenly the man’s tone changed. “Tradition is important to me, but not the current tradition,” he said with a stiff voice. “Today, I don’t mind seeing everything go up in flames.”

This young man was expressing frustration with the stark contrast between his liberal worldview and the fundamentalism that dominates the politics of his country. The substantial gap between the autocratic government and the Iranian people was unveiled in this innovative survey, conducted in Iran in 2011.[i] The study of over 900 respondents measured Iranian society’s potential for liberal democracy based on its value structure. The study found that Iranian society has stronger liberal tendencies than Egypt and Jordan, and even – outside of the Middle East – countries like Ukraine and Romania, among others. The results of this work reveal a different Iran than is commonly perceived. Findings point towards new courses of action that can be taken in the Middle East, which consider the potential that Iranian society represents for liberal leadership in the region.

Seeds of Hope

We are living in a new era in the Middle East. As Israelis, we grew up hearing about the fierce and menacing Iraq and Syria; it is humbling to think the countries as we knew them no longer exist. Astoundingly, it took the Islamic State only four months to capture an area the size of Britain.[ii] Meanwhile, Iranian and Saudi money, weapons, and ideology have a heavy presence in almost every conflict zone in the region.[iii] Bloody wars in Syria, Iraq, and Yemen are fueled by the Iranian regime’s hegemonic ambitions. Peoples in failing countries, searching for meaning and leadership, can currently find answers only among extremist leaderships such as those in Iran and Saudi Arabia and fundamentalist organizations such as the Islamic State. There is a lack of vision and leadership for any other future.

The rest of the world, dealing with a grave refugee emergency and watching as oppressive regimes and violent organizations challenge the most extreme lines of morality, seems to be at a loss for how to deal with this crisis.

Research we conducted together with our partner Yuval Porat sheds new light on this regional turmoil. In 2011, against the backdrop of the Arab Spring, we decided to explore not the superpowers, regimes or terror organizations, but rather the people of the Middle East. The Arab Spring presented many opportunities for positive change in this part of the world, but in countries such as Egypt and Libya, these opportunities soon went sour as proponents of freedom found themselves in the minority. It seemed that although citizens were succeeding in overthrowing their autocratic regimes, they were not steering their countries in a more liberal and democratic direction.[iv]

Our objective was to examine whether there are societies in the region that are characterized by liberal values and a potential for meaningful democracy. We focused on Iranian society—a people of an ancient culture and heritage, reputed to have values of progress and unfulfilled dreams of political pluralism and liberty. We conducted first-of-its-kind research to examine where the majority of the Iranian people stand between the forces of liberty and extremism. The aim was to reveal the principal values that characterize Iranian culture, in order to measure its people’s potential to foster a liberal society and meaningful democracy.

Notably, it is of special significance that a team of Israelis conducted this research. We did so not out of fear or suspicion, but rather out of curiosity. As residents of a region going through extreme upheaval, we identified a possible source of hope and decided to explore quantitatively. At a time when Iran is viewed as Israel’s greatest threat, we chose to observe Iran not as an icon of Islamic extremism, but instead as home to a complex and diverse society.

Overcoming the Fear Bias

According to Iranian urban legend, half a million handicapped veterans of the Iran-Iraq war are employed by the Iranian regime to tap every phone call in the country. Regardless of how much truth there is to this myth, every survey conducted in Iran that even faintly smells political is treated with suspicion and fear that could cast doubt on the credibility of the results.[v] As an English proverb says, however, necessity is the mother of invention. Overcoming this fear bias required us to come up with a methodological innovation.

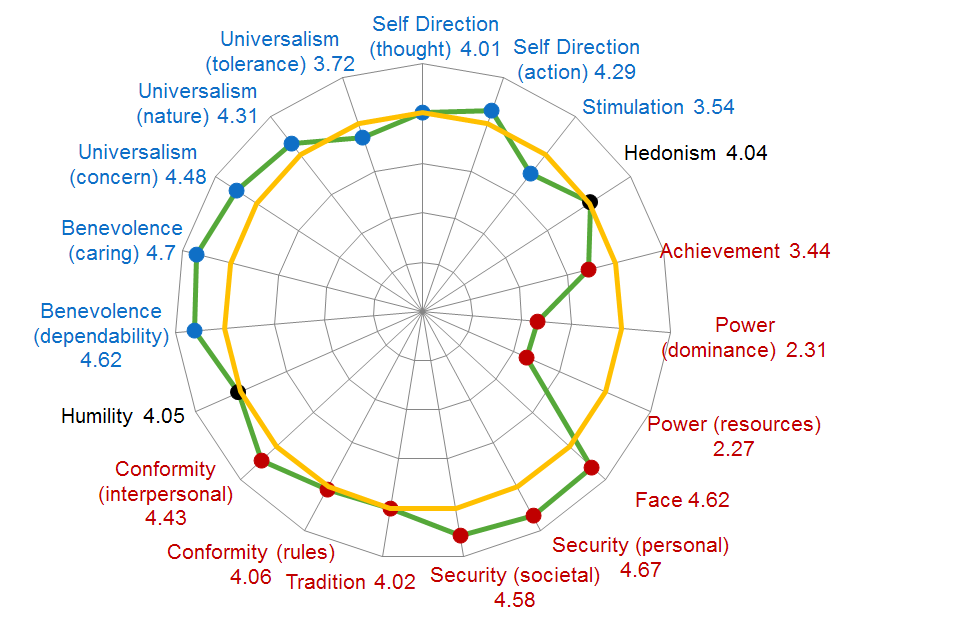

Teaming up with Israel Prize laureate Professor Shalom Schwartz from Hebrew University in Jerusalem, we developed a measure of liberal attitudes based on a seemingly innocuous psychological questionnaire. Over more than two decades, Professor Schwartz, a world-renowned expert in the field of cross-cultural psychology, developed the Theory of Basic Human Values—a universal theory for the content and organization of the values systems of individuals, valid across cultural and national boundaries.[vi] This theory was validated using 160,000 subjects from sixty-two different countries, from Sub-Saharan Africa to Scandinavia. Professor Schwartz and his colleagues identified nineteen distinct basic human values, differentiated by the type of motivational goal they express (i.e., security, achievement, conformity, etc.). These values form a circular structure of contradicting or tangent relationships between one another. People differ substantially in the importance they attribute to the values, but the recognition and organization of the values are common across most literate adults around the world (see Chart 1).[vii]

Chart 1: Schwartz’s 19 Basic Human Values

The significance of Schwartz’s Theory of Basic Human Values is that the questions appear to be part of an inconspicuous psychological survey, such as the following:[viii]

“How similar are you to someone for whom accepting people even when he disagrees with them is important?“

“How similar are you to someone for whom maintaining traditional values or beliefs is important?”

However, the findings of different value sets correlate with very specific individual behaviors and attitudes, such as choice of university major, attitudes towards immigration,[ix] and even voting patterns.[x] On the collective level, the prevalence of certain value structures has been closely associated with democratic societies. Therefore, the use of The Theory of Basic Human Values allowed us to test people’s liberal attitudes indirectly, while bypassing the fear bias and protecting the respondents from persecution in case their participation was revealed.

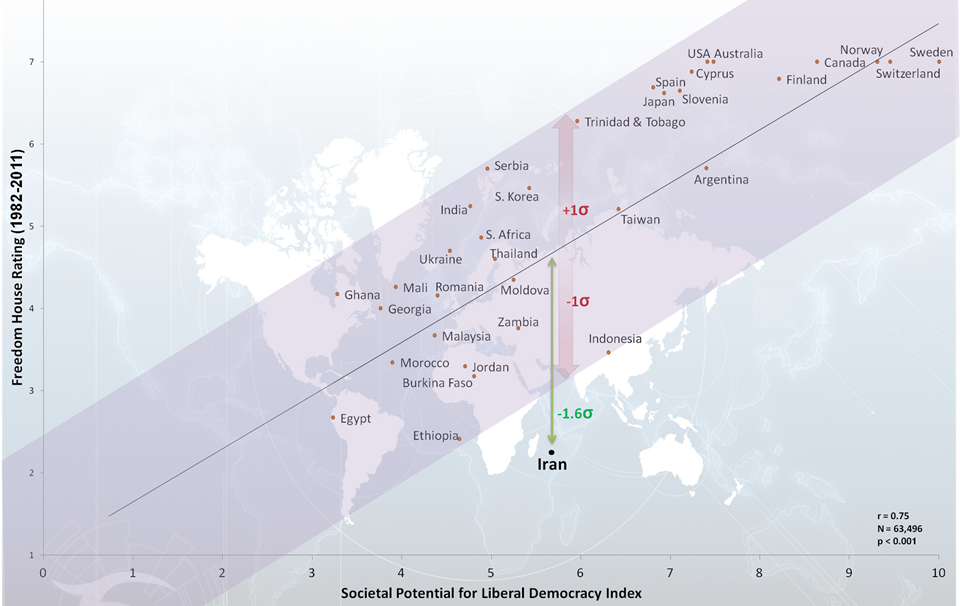

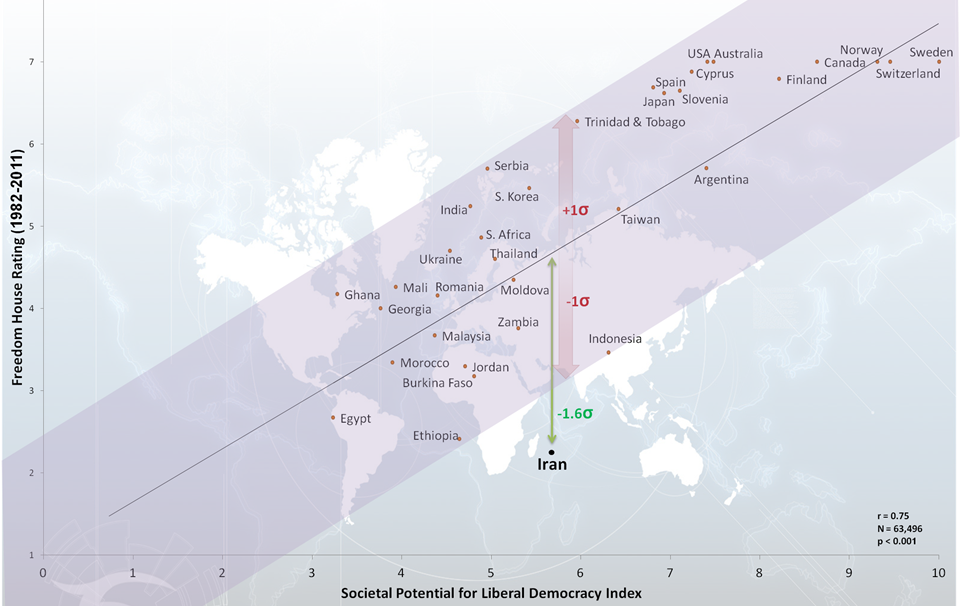

To provide a comparative tool for evaluating a society’s potential for liberal democracy based on its values, we formulated the Societal Potential for Liberal Democracy Index. Under the guidance of Professor Schwartz, we analyzed the value sets of 160,000 survey respondents in relation to the degree of political and civil liberties in their countries (as measured by Freedom House).[xi] We found a positive correlation between a high degree of political and civil liberties and values such as universalism, benevolence, and self-direction; we also found a negative correlation with values such as conformity, security, and power. We used these findings to compose a unified score that reflects individual and collective support for liberal democracy, based on observed values.

Behind the Electronic Curtain

Once we formulated the methodology, we turned to another challenge in administering the questionnaire in Iran—the language barrier. The questionnaire had to be translated into Farsi with the utmost accuracy in order to preserve the finer connotations and nuances of the English questionnaire. When dealing with abstract and complex concepts such as values, any deviation from the questionnaire administered in other countries runs the risk of being incomparable. A team of professional English-Farsi translators, including native Farsi speakers and academics in the field of Farsi linguistics, conducted seven rounds of translation and back-translation to ensure maximum compatibility with surveys in English and other languages.

An additional challenge was overcoming the weak phone penetration in Iran. Communication infrastructure in certain rural regions is unreliable and prone to breakdowns. In addition, there is no phone directory in Iran, making it difficult to find survey subjects and impossible to sample the population in a representative way. To address this challenge, we innovated a technological solution that automatically and randomly acquired and verified landline and mobile phone numbers from all thirty-one provinces in Iran, in both urban and rural areas. Since there is a high correlation between geography and ethnic association, our technological solution assured a random and representative sample of all six main ethnic groups in Iran (verified by respondents’ self-testimony and mother tongue). Finally, since the sampling was random, equal numbers of women and men were included.

A New Perspective on the Iranian People

To administer the survey, we recruited and trained twenty members of the Jewish-Iranian community in Israel, who agreed to voluntarily conduct the telephone survey in Iran out of a strong sense of pride in their Iranian heritage. The surveyors were native speakers who spent the majority of their adult lives in Iran. They were intimately familiar with Iranian culture and etiquette, and spoke Farsi with flawless accents. These measures were crucial to avoid recognition, since identifying the surveyors as Israeli could have skewed the responses as well as compromised the security of the respondents.

The survey was conducted between 24 October 2011 and 31 December 2011. The interviews were conducted from Israel, through a secure and untraceable telephone system, and were monitored in real-time for quality control and precise sampling.

In total, 914 Iranians were interviewed, constituting a representative sample of the entire Iranian society across segments of geography, ethnicity, gender, age, and marital status, with only minimal weighing required. The data and the findings were reviewed and validated by leading experts in the fields of Iranian society, cross-cultural research, and statistical methodology. The highly representative sample allowed us to draw conclusions regarding Iranian society at large.

We analyzed findings to produce the value set that characterizes Iranian society (see Chart 2), and compiled to calculate Iranian society’s score on the newly formulated Societal Potential for Liberal Democracy Index. We then compared Iranian society’s score to the scores of sixty-two other countries, ranging from developing states such as Ghana, Indonesia, and Egypt to developed ones including Sweden, France, and the United States.[xii]

Chart 2: Iranian Society’s Value Set

Graph 1: Countries’ liberal potential and actual level of liberal freedom

Stirring a Public Discussion in Iran

These research findings were published in a Wall Street Journal op-ed on 13 May 2012, and later featured in events and discussions at prominent research institutions including the German Marshall Fund,[xiii] the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, the Hoover Institute, the RAND Corporation, and in US State Department briefings.[xiv] Iranian media outlets soon caught wind of the article as well: over 100 Iranian media outlets, including those closely linked with conservative factions and the Supreme Leader, reported and debated the research.[xv]

A New Way Forward in the Middle East?

The struggle between ideas is one of the most significant factors influencing the choices of individuals and the course of human history. Nowhere is the battle more apparent today than in the Middle East. The region is experiencing a crisis not just of arms, but also more fundamentally of identity and vision.

Iranians, and other Middle Eastern peoples, should not be viewed solely through the prism of the extreme elements that have a hold on their countries’ political institutions, but rather through the struggle of conflicting and interlocking values among their complex and diverse societies. Middle Eastern liberal societies—yes, they exist—provide the only long-term path to a freer region.

The strategic and long-term battle against extremist and violent elements in the Middle East cannot be defeated solely at a military level. It also cannot be defeated exclusively at the diplomatic level, through engagement with suppressive regimes and extremist organizations over the heads of citizens. Rather, this battle must also be fought at the level of hearts and minds, in partnership with the people in the region who are liberal and yearning for freedom.

Fostering an alternate, authentic and convincing vision and leadership is imperative to lessen the hold of extremist ideologies. To do so, existing organic liberal currents should be identified and supported. Specifically, the Iranian people have extraordinary intrinsic liberal values that, when coupled with Iran’s substantial regional influence, make the country a potential leader for a freer and more tolerant Middle East.

The Iranian nuclear deal signed last year between Iran and the UN Security Council’s five permanent members plus Germany provides an opening to redefine engagement policy and strategy with regards to Iran.

Our proposition is that a significant cornerstone of American and, more broadly, Western policy should be to foster the potential of the people within Iran as regional leaders, by encouraging cultural openness and stronger communication between the outside world and Iranians. Due to its immense impact on the region, a more liberal Iran can serve as a model for liberal and democratic Islam. It holds tremendous promise for the advancement of a freer and more hopeful Middle East. In parallel, other liberal forces in the region should be identified and supported in this way.

Our hope is that one day the Iranian people, and other liberal forces in the region, will represent a new way forward in the Middle East.

Yael Stern and Gal Lin are foreign affairs professionals and entrepreneurs who grew up in Israel. For the past four years they have partnered to promote peace in the Middle East through empowering civil society. They are pursuing master of public policy degrees from the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University.

Yael Stern and Gal Lin are foreign affairs professionals and entrepreneurs who grew up in Israel. For the past four years they have partnered to promote peace in the Middle East through empowering civil society. They are pursuing master of public policy degrees from the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University.

The authors’ complete research, which informed this piece, can be accessed at www.iranresearch.org.

[i] Yuval Porat, Yael Stern, Gal Lin, Ester Asherof, and Alex Karpman,”Could Iran Turn Into a Liberal Democracy?” (Research Paper, 2012), accessed 6 January 2016, iranresearch.org/ReadTheFullResearch.

[ii]Rick Noack. “Here’s How the Islamic State Compares with Real States,” TheWashington Post, 12 September 2014, accessed 1 February 1 2016, www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2014/09/12/heres-how-the-islamic-state-compares-to-real-states/.

[iii]Simon Henderson. “The Battle for Iraq Is a Saudi War on Iran,” Foreign Policy, 12 June 2014, retrieved from foreignpolicy.com/2014/06/12/the-battle-for-iraq-is-a-saudi-war-on-iran/.

Tom Risen. “Arms Sales Boom amid Iran, Saudi Arabia Proxy Wars,” U.S. News, 22 February 2016, retrieved from www.usnews.com/news/blogs/data-mine/2016/02/22/arms-sales-boom-amid-iran-saudi-arabia-proxy-wars.

Ariel Ben Solomn. “Iran-Saudi sectarian proxy wars set to explode, Israeli experts say,” The Jerusalem Post, 4 January 2016, retrieved from www.jpost.com/Middle-East/Iran-Saudi-sectarian-proxy-war-set-to-explode-Israeli-experts-say-439378.

People gather at a bombed site in Sana’a after Saudi-led air strikes

People gather at a bombed site in Sana’a after Saudi-led air strikes. Photograph: Hani Ali/Xinhua/Corbis

Simon Tisdall. “Iran-Saudi proxy war in Yemen explodes into region-wide crisis,” The Guardian, 26 March 2015, retrieved from www.theguardian.com/world/2015/mar/26/iran-saudi-proxy-war-yemen-crisis.

Paul Rogers. “Syria, the proxy war,” Open Democracy, 14 June 2012, retrieved from www.opendemocracy.net/paul-rogers/syria-proxy-war.

“Saudi Arabia vs. Iran: The Sunni-Shiite Proxy Wars,” The Wall Street Journal, 7 April 2015, retrieved from www.wsj.com/video/saudi-arabia-vs-iran-the-sunni-shiite-proxy-wars/A7B70696-9A6D-4B26-88EC-BBFDD44AE112.html.

Associated Press. “Iran, Saudi Arabia fighting bloody proxy wars across the Middle East,” Fox News, 26 March 2015, retrieved from www.foxnews.com/world/2015/03/26/iran-saudi-arabia-fighting-bloody-proxy-wars-across-middle-east.html.

[iv]Butt, Gerald. “Viewpoint: Why Arab Spring has not Delivered Real Democracy”. BBC News, 2 June 2014, retrieved from http://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-27632777

[v]Porat, Stern, Lin, Asherof, and Karpman, “Could Iran Turn Into a Liberal Democracy?”

[vi]Shalom H. Schwartz, “Universals in the Content and Structure of Values: Theoretical Advances and Empirical Tests in 20 Countries,” Advances in Experimental Social Psychology Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 25 (1992): 1-65, accessed 13 February 2016, numerons.files.wordpress.com/2012/04/40-universals-in-the-content-and-structure-of-values.pdf.

[vii]Shalom H. Schwartz et al., “Extending the Cross-Cultural Validity of the Theory of Basic Human Values with a Different Method of Measurement,” Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 32, no. 5 (2001): 519-42, accessed 13 February 2016, jcc.sagepub.com/content/32/5/519.abstract?cited-by=yes&legid=spjcc;32/5/519.

[viii]Yuval Porat, Yael Stern, Gal Lin, Ester Asherof, and Alex Karpman,”Could Iran Turn Into a Liberal Democracy?” (Research Paper, 2012), accessed 6 January 2016, iranresearch.org/ReadTheFullResearch.

[ix]Shalom H. Schwartz, “Les Valeurs De Base De La Personne: Théorie, Mesures et Applications,” Revue Française De Sociologie 47, no. 4 (2006): 929, accessed 13 February 2016, www.jstor.org/stable/20453420?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents.

[x]Gian Vittorio Caprara et al. “The Personalization of Politics,” European Psychologist 13, no. 3 (2008): 157-72, accessed 13 February 2016, econtent.hogrefe.com/doi/abs/10.1027/1016-9040.13.3.157.

[xi] Freedom House, Checklist questions and guidelines (2011), accessed 13 February 2016, www.freedomhouse.org/template.cfm?page=351&ana_page=374&year=2011.

[xii] The data for other countries comes from two sources: the World Values Survey (WVS) and the European Social Survey (EES). Both surveys run periodically in representative samples of select countries, and include different versions of Schwartz’s values questionnaires. The EES focuses on European countries (plus Israel) while the WVS includes countries from all over the world.

World Values Survey, Wave 5 (2005-2009), accessed 13 February 2016, http://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSDocumentationWV5.jsp.

European Social Survey, Rounds 4 & 5 (2008 & 2010), access 31ed December 2011, www.europeansocialsurvey.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=41&Itemid=73.

[xiii]Yuval Porat, “Iran After the Mullahs: A Liberal Democracy?” (research presented at a German Marshall Fund event, Washington DC, September 6, 2012).

[xiv]Yuval Porat, “Iranians Have Democratic Values,” The Wall Street Journal, 13 May 2012, accessed 1 February 2016, www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052702304363104577392050519982974.

[xv]Bagherpour, Mehdi. “New Study of Iranians’ Democratic Values Causes Stir”, PBS, 30 May 2012, retrieved from http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/tehranbureau/2012/05/comment-new-study-of-iranians-democratic-values-causes-stir.html