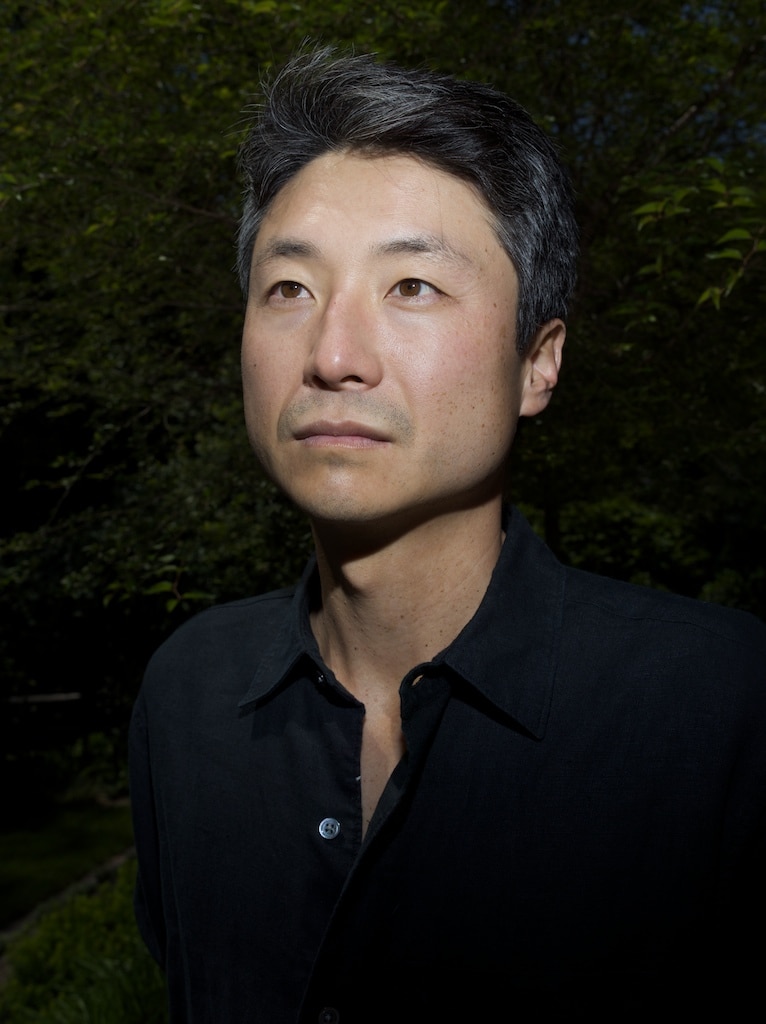

Chang-rae Lee is the author of Native Speaker, winner of the Hemingway Foundation/PEN/Hemingway Award for first fiction; A Gesture Life; Aloft; and The Surrendered, winner of the Dayton Peace Prize and a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. Selected by the New Yorker as one of the “20 Writers for the 21st Century,” Lee is professor in the Lewis Center for the Arts at Princeton University and a Shinhan Distinguished Visiting Professor at Yonsei University. His most recent book is On Such a Full Sea.

This interview took place on 23 January 2015.

AAPR: Before becoming a novelist, you worked on Wall Street as an equity analyst. Tell us about your transition from finance to writing.

LEE: I always wanted to write. I always held in the back of my psyche and spirit that it would be nice to be a writer; it would be nice to write both as an activity and as a vocation. But, I don’t think I ever held myself the luxury of that thought or at least the sustained thought that I could make a life that way. That’s partly because of the way I’ve been raised. My parents were very generous and in many ways liberal-minded people. However, their conception of what I would do and what we were all doing as an immigrant family, without a safety net or a tradition of a certain kind of cultural life in this country . . . writing just wasn’t part of the equation. I took that job not because I really wanted to work on Wall Street. More than anything else, I just really wanted a job and it was the best available job.

AAPR: And it isn’t a bad job to have right out of college.

LEE: [laughs] No, it was a very good job. I actually enjoyed the work, and I especially enjoyed my colleagues. They were all incredibly smart. But one of the things about that job that struck me was that many of my colleagues were only at the firm until they could do what they really wanted to do. Some of them even wanted to write novels! During that time, I was living with a close friend of mine from boarding school and he also loved to write. His name is Brooks Hansen and he found early success publishing a jointly written first novel, Boone, which got a good amount of attention. That inspired me.

I had written a lot in high school. Not so much in any formal way during college. But again, writing was something that I wanted to do. So once I got to that idea, I felt as if I should give writing a chance and that it would be better to give it a chance now rather than “make millions of dollars and do it when I’m forty-something years old,” which everyone says they’re going to do. But life is totally different then. Our consciousness is totally different. Our circumstances are totally different. And it’s much, much harder to start writing then.

I decided to quit my job just after a year and take the leap, thinking that it would be better for me to try it then. Also, it was probably easier to convince my parents that it was a better moment for me to do it—to try to write for a few years, and if it didn’t work out, go back to doing whatever. My parents always hoped I would go to law school because I was an English major or that I would go back to Wall Street. I suppose I didn’t have too many worries about that. I, too, thought that could always happen because I was still young. But I wanted to give it a shot then, so I did.

AAPR: After leaving Wall Street, you enrolled in the MFA in writing program at the University of Oregon to pursue your craft. Were there obstacles you faced as an emerging Asian American novelist?

LEE: I think I was very fortunate. I know that many writers of color who go to MFA programs have had a difficult time presenting, discussing, and receiving critique on their work. Junot Diaz has famously written about that, about writers of color having real challenges in MFA programs, whether it’s because those programs don’t recognize them or that the kinds of way they talk about “ethnic fiction” is often based in ignorance, bias, or other sorts of disheartening or dispiriting kinds of discourse.

AAPR: Were some of these kinds of discourse something that you had experienced or at least overheard?

LEE: I had heard about that, but I was fortunate because the new director of the program at Oregon at the time was Garrett Hongo, a Japanese American poet who grew up in California with deep Hawaiian roots and who was very much conscious of these issues in his workshops. He was a poet and I knew we weren’t going to work together in terms of writing technique; however, I felt like he was an artistic mentor for me. And he really was. He helped me situate my work in the context in which I wanted to see it, rather than another kind of context in which I would have to constantly explain myself or have to constantly struggle against. I think this is a problem a lot of writers of color at these programs end up facing.

Writing is hard enough, but when you have to constantly educate or contest the context or language by which that work will be discussed, it can be an obstacle that stops writing. It inhibits creativity. So, I didn’t have those feelings. I did have some instructors that weren’t that helpful, but the atmosphere and tenor of the program was really inspiring.

AAPR: Things have come full circle for you. As a professor of creative writing at Princeton University, you now serve as a mentor to a younger generation of writers. What led you to pursue teaching?

LEE: I assumed that after my graduate work, I would go back to New York and live the life of a writer—publish a book and do all that. [laughs] I did publish a work, but Garrett asked me to stay on as an assistant professor in the program. I had taught some writing sections as a graduate student and enjoyed it. I thought it would be a nice way to support myself because with the kind of writing that I do, you’re not writing to make money. You would like to make money and you’d like to have a large readership, but no one would go into writing literary fiction because they thought they could really support themselves. [laughs] I also thought teaching would give me some stability. I knew I wanted to have a family someday so I thought that would be a good thing.

In reflection, I guess it just turned out to be something that I always did in concert with my writing just from the start. So just in terms of my creative energy and intellectual partitioning, I guess it all developed from the start so that I could do both. And I really enjoyed my teaching over the years.

AAPR: I imagine the challenges of being a writer and the challenges of someone guiding writing are totally different.

LEE: They totally are. When I’m in the classroom, I’m focused on what the creative and intellectual needs of that particular student are. We discuss things that will help them create a more ideal approach to their work. I’m not trying to make my students write like me or think like me. Instead, I’m trying to figure out what they want to write about and how to optimize that. It’s really like a therapist in that way. You’re trying to listen, trying to observe. Of course, you have your own opinions, but those opinions are in service of helping them as much as possible. Obviously, you have your own set of experiences and knowledge about writing and literature, and you bring that to it, but I hope it’s not ego driven.

It is totally different when I’m at my writing desk. It’s all about shoving everything else out. It’s about a pure kind of focus on what I want to see, hear, and feel in terms of superlatives. Teaching and writing, in fact, they’re sort of opposite activities. And I try not to bring my teaching life into my writing life.

AAPR: Do you find that difficult to do?

LEE: I actually don’t find it that difficult. Maybe it’s because I’ve always done it, that I’m used to putting up those walls. I know that other writers have said, “I hear myself giving advice, I hear myself giving advice!” [laughs] I don’t think artistically that really works. Artists are always exhorting themselves, or counseling themselves, but in a slightly different way than you might as a teacher.

AAPR: The success of your earlier works like Native Speaker and A Gesture Life led many in the literary world to appoint you as the next great Asian American writer. What are your thoughts on such a coronation? Were there any burdens or frustrations you felt with this label?

LEE: It’s always nice to be recognized and noticed. Different readers and different quarters of the reading public will have different interests when discussing writers. The “leading Asian American writer” moniker, all those kind of things, was always to me more necessary for the reading public than for the writer. [laughs] The reading public, whether it’s for commercial, philosophical, or cultural purposes . . . that’s how some people are able to understand or catalog people. It’s really more about that than any truth or legitimate position that a writer can take. We can always talk about who are the great American writers, and obviously it’s subjective and it’s always dynamic, and there’s not really one thing, never one set of lists that is definitive.

In the end, I’m not frustrated. Rather, I try to think of it, and I really see it as, something totally outside of me, as something that I do not want to have ingrained in any of my consciousness about myself because I know that such labels really mean nothing. What’s really important is that I work with integrity and passion and respect to the art.

AAPR: In your earlier novels like Native Speaker, you explore Asian American identities and, to a larger degree, outsider identities. Do such themes arise from your own personal upbringing as a person of color in the United States?

LEE: It does have my experiences in it. I would say that my experience as a private person and what I empirically know is much less dramatic than what I write about. [laughs] When you write about things, there’s an accentuation going on, a kind of crystallization that requires certain dramatic and lingual actions that weren’t going on in my regular life. So, I don’t want to say this is my life and this is what I write. It’s not exactly like that. But these are the sets of sensitivities, stances, and positions in the culture that I’ve had over the years. One of those positions is to be an observer, someone who understands that he’s not completely aligned with the context or culture that he inhabits. That there is a sense of difference or certain kind of dissonance between those two entities. So yeah, that’s something that I’ve often written about. Not so much in my last two books, particularly my fourth book, but it’s always there. But again, as with any writer, that writer does live life and observe things differently. So again, it’s part of what has generated a lot of my thinking. I don’t know how much of that will figure into my future work.

AAPR: In your most recent novel, On Such a Full Sea, you write of an America afflicted with class struggle, climate change, and health epidemics. It’s impossible to not see the parallels with the issues we face today. Are you a keen follower of current events, news, and politics, and do you try to incorporate these things into your writing?

LEE: I would say that I’m a very avid newspaper reader—the political pages, business pages, culture sections . . . I guess I try not to live in the world but instead try to keep abreast of all the things that are happening. If you are a keen reader of this or just an avid reader of a good newspaper or journal, there are a lot of things going on that are deeply, deeply alarming. [laughs] I think that those things are a part of who you are and they certainly a part of who I am. That doesn’t mean I sat down with On A Full Sea and said, “I’m going to write about these issues.” But whenever you write about the world, and even if it’s a speculative world, that world does include human beings and their pursuits, beliefs, and fears. I guess that all these issues that I’ve just been anxious and concerned about—class differences, the environment, health care, income inequality—they all just bubbled up to the surface.

AAPR: The society that you construct in your latest book is a rigidly stratified between the haves and have-nots. Does this come from a personal view or critique you hold on contemporary America?

LEE: I think the book is a critique on a lot of things. It’s a critique on American status and its decline. It’s a critique on class and the rigid structures that we have in our society. On the ways in which our government and our tax codes reward certain activities and not others. [laughs] It’s a critique of a kind of, I would say, deeply neurotic energy that I think all this kind of fraught living is reaching upon us spiritually and emotionally, as so-called civilized people. It’s a compendium of all my anxieties and qualms.

AAPR: Would you call yourself an anxious person? Or maybe just someone with many thoughts?

LEE: Well, I think those two things go hand in hand. [laughs] Probably in the scheme of things, I am more anxious than others. I probably don’t seem anxious to people, but the run of thoughts is, if you keep thinking about all of these issues and their aspects, it’s hard to get out of them. It’s hard to look at them and remain calm.

AAPR: Speaking of anxiety, there have been a number of films and books that were released this past year, leading many to see 2014 as the year of the dystopia. I am curious of your thoughts on why our society is obsessed with the end.

LEE: First, I never thought of On Such a Full Sea primarily as a dystopian novel. It obviously does have some dystopian features, but I think the book uses it as a backdrop and is more concerned about other things, including some of the issues we discussed.

But to answer your question, I think that we all have a sense, and I don’t know if it’s just Americans, but also “developed nation peoples,” that we are profoundly out of balance in our world and in our society in various aspects. Whether we’re environmentally, economically, financially out of balance, we are in precarious positions. We’re always on the cusp of some bubble. And I think that that’s what people are feeling. It’s a feeling that perhaps we’re using both our world and ourselves up at a rate that can lead only to disillusion and disaster. I think people have always worried about the end of the world, but perhaps more so now because we have so much information on things that are going on. We need our imagination to understand how fragile things might be. So I think it’s a natural result of all the information that we have.

AAPR: Is there anything else you would like to pursue besides writing?

LEE: I think it would be fun to write for a television show. Just for something different. Let me take a step back. Maybe create a show and lay it out rather than write one. [laughs]

AAPR: A sitcom or something more dramatic?

LEE: It could be either a sitcom or a dramatic series. There are some funny or screwy ideas that I would like to exercise that I think aren’t particularly great for novel forms, but may be more appropriate for a television format. But that’s just stuff I dabble with and not seriously pursuing because between the teaching and writing novels, I barely have enough time.

AAPR: What do you like to read for fun?

LEE: I read a lot of different things. I read a lot of novels. A lot of novels are sent to me. I read some philosophy, and I read the paper. [laughs]

A novel that I recently enjoyed a lot was In the Light of What We Know by Zia Haider Rahman. In fact, he used to be a banker! [laughs] It’s his first novel, but it’s quite a brilliant novel. He’s a South Asian writer who talks about a lot of different things in his book: epistemology, love, race and ethnicity, mathematics, post-9/11. A book about a lot of different things that I think AAPR readers will find particularly gripping.

AAPR: Our journal’s audience is mostly younger Asian American students and readers. As you can personally attest to, many young Asian Americans tend to choose more traditional and stable career paths instead of something more passionate like the arts. Any words of wisdom for our readers?

LEE: We have such talented people with lots of energy and ideas in our community. I just can’t believe that all that talent is meant to be in three or four fields—banking, consulting, law, medicine. [laughs] If you really think about it, right now is an exciting time because our community is really starting to get established. We have to remember we’re still, in the most diverse way, a very young community. I know that there were Chinese Americans and Japanese Americans here from many years ago, but since 1965, the full range of Asian diversity in this country has really blossomed. So I think we’ve now become a little more established. I think it really behooves us to go out into these other fields, including government, maybe especially government.

The one thing that I would say is there are many ways to pursue an honorable, prosperous, and significant life of work, and I think we’re established enough to really believe that.