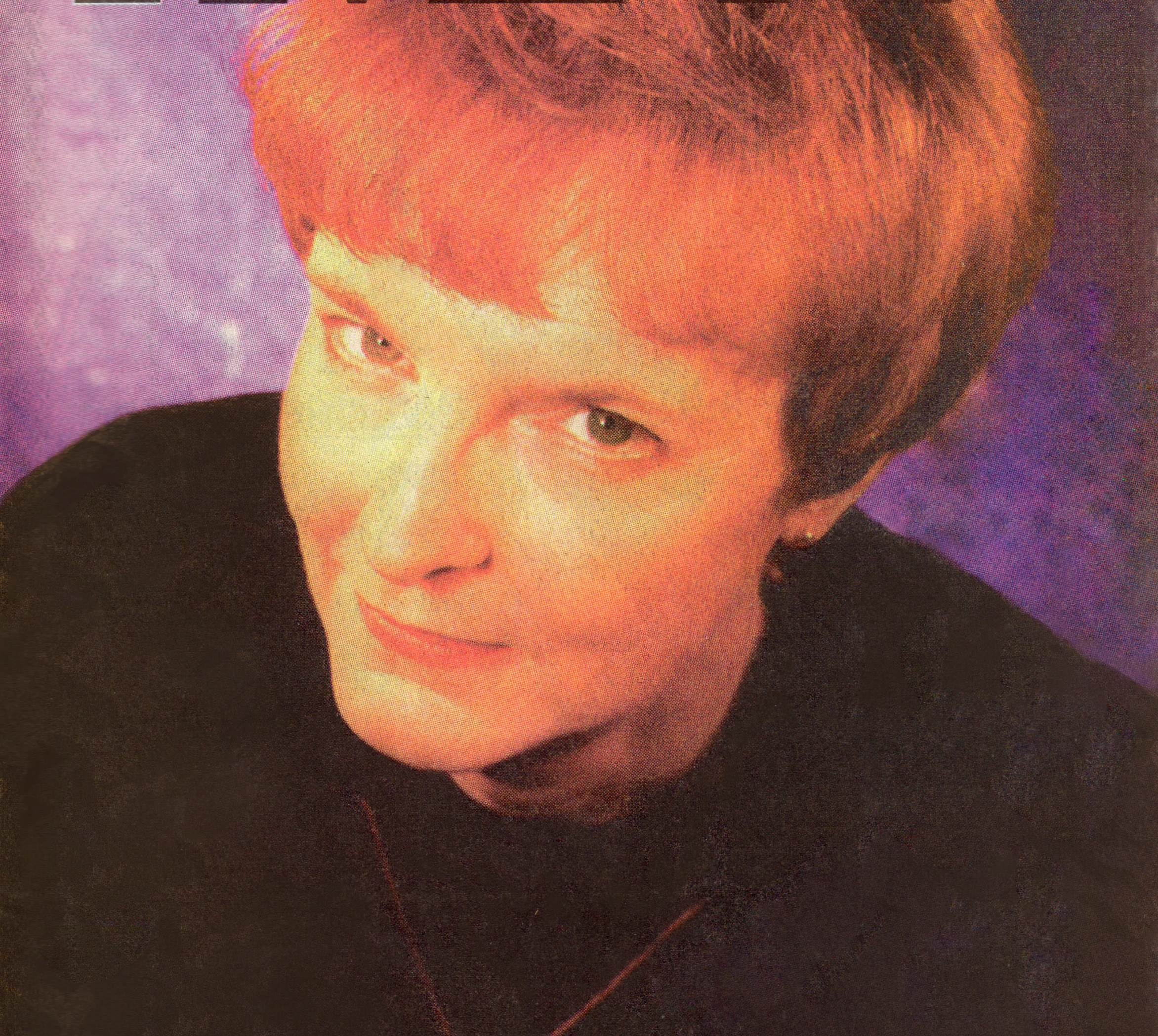

Jessica Xavier has been a leading trans activist, scholar, and artist for more than 25 years. She was the co-founder of the first nationally organized grassroots political action and lobbying group for transgender people, It’s Time, America!, in 1994, and also co-founded Gender Education and Advocacy in 2000. Jessica is also a pioneer in transgender-related data collection, working for over 35 years in and around the HIV epidemic, including more than a decade in the federal government with the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program. Her work has been recognized by numerous awards including the highly prestigious Public Service Award from the Society for the Scientific Study of Sex (alongside two former US surgeon generals) and the Distinguished Service Award presented by the Gay and Lesbian Activist Alliance. She is also an accomplished singer/songwriter, and in 1999, she released Changeling, one of the first trans music CDs. Perhaps more importantly, Jessica has been a role model and inspiration to countless individuals, trans and otherwise, opening many doors for the increased understanding, support, and acceptance of a number of disenfranchised communities.

RYAN: You have a considerable, and impressive, history related to trans activism. Can you tell us what first inspired you to become an activist for trans rights?

XAVIER: After I came out, I became the outreach director for the Transgender Educational Association of Washington, DC. In that capacity I answered a call for volunteers for the host committee for the 1993 March on Washington for Gay, Lesbian and Bi Equal Rights and Liberation (MOW). I met many gay men and lesbians who were out, loud, and proud and became inspired by their courage and commitment toward gaining their civil rights. So participating in the 1993 MOW politicized me, along with other transgender people who realized we had to emerge from the shadows and openly advocate for ourselves if we were going to live our lives free from discrimination and violence. The only justice we receive, we must create for ourselves.

There once was a perceived tension between the LGB and the T in activist circles. What do you think is the relationship between the T and the LGB in terms of social activism?

I believe that all queer folks are simply seeking the same civil rights that straight, cisgender people (people who do not identify as transgender) take for granted. We have learned to work together in common cause to fight discrimination and violence and to obtain recognition of our marriages and families. But trans people are different in that we need access to specialized medical care for our physical transformations in order to be comfortable in our bodies and safe from stigma-driven violence and discrimination. We also have to re-document our identities and fight to have our chosen genders recognized and respected.

Some might argue that the early days of the LGBT movement were really just an LGB movement, with the T often being either ignored or thrown under the bus for the supposed sake of political advances. Arguably, however, this situation has improved somewhat over the last decade, with increasing attention being paid to the T in its own right and, in fact, the growing, albeit still limited, prominence of organizations that focus exclusively on T issues. How do you respond to this assessment?

There was once a time when we were all just gay, before identity politics separated us into a hierarchy of oppressed groups. Then in the 1990s, there was an enormous struggle by trans people to be included in the larger, better-organized gay and lesbian civil rights movement. There were those who thought trans people were completely different from gay and lesbian people, even though we all fought at Stonewall together. And some were all too ready to put a dress code on civil rights. So lots of education became necessary, sometimes with people who did not want to listen. This struggle absorbed much of my time and effort and brought me into conflict with gay and lesbian advocates whom I looked up to and admired for their courage and industry. So we had to form parallel organizations of our own to work beside gay and lesbian organizations to advocate and educate. I tried to organize the groups I co-founded based on my transfeminist principles, but I largely failed to gain acceptance of this approach.

Can you tell us a bit more about what these transfeminist principles are and why you feel they failed to gain acceptance with the larger movement?

Transfeminism builds upon the intersectional understandings of oppression based on sex, race, class, age, poverty, etc. Its demand for bodily autonomy and access to the transformational medical procedures that allow our bodies to correspond with our true genders parallels reproductive choice for cisgender women. However, it critiques traditional second-wave feminism that predicates its opposition to gender-based oppression (GBO) on identity politics and how it dumbs down GBO to only where it intrudes into narrowly drawn identity boxes, such as “women” and “lesbians.” Inherent in transfeminism is a call to action to not just fight GBO but to dismantle compulsory, heteronormative gender itself, thus transcending sexism, homophobia, biphobia, and transphobia to focus on the actual disease of GBO rather than just its symptoms.

I was a feminist for at least 15 years before I transitioned, and I became one of the early transfeminists after reading Sandy Stone’s ovarian essay, The “Empire” Strikes Back: A Posttranssexual Manifesto.[1] For me, transfeminism emerged as a reaction to a particularly vicious form of GBO, which is generally called transphobia. In my survey research, I’ve assessed transphobia’s measureable outcomes including murder, physical, and sexual assault; discrimination in employment, education, housing, and health care; and suicidality and substance abuse. Thus transfeminism began as a politics of survival. I like to say that if you have time to write about transfeminism, you are probably not practicing it. But I suppose everyone needs to take a break now and then [laughs].

In my 1995 essay, “Transsexual Feminism and Transgender Politicization,”[2] I analyzed why so few transgender people were actively participating in the movement. There were hardly any transmen and transpeople of color showing up at our meetings, so our transpolitical agenda was mostly driven by transwomen and male crossdressers. I saw a lot of competition among the few national organizations; personal rivalries; and worse, no underlying, inclusive politics to inform the movement. I also saw the diversity of the trans population as an unused asset, while too many people were being driven away by leadership’s bent on retaining their White, male, passing privileges. So in It’s Time, America! and It’s Time, Maryland! I tried to incorporate feminist process and consensus-based decision-making in our meetings, to bring in the voices of everyone who showed up. We outreached to transpeople of color and transmen to bring them into our groups and agendas. It was radical, it was revolutionary, it was way too far ahead of its time, and so it failed. The movement remained an attorney-driven, patriarchal “gimme my rights back” endeavor, seemingly seeking to reclaim lost privilege.

How do you view the goals and strategies of the trans-rights movement as having evolved over the last several decades?

It seems to me that the primary focus has continued to be on anti-transgender violence. Kay Brown did an analysis once and found that it was more likely for a transwoman to be murdered than to be married. But other issues, like discrimination in employment, education, housing, and health care and recognition and re-documentation of our legal identities, have also seen some focus and progress. Regrettably, the extent of HIV infection among transgender people, primarily among transgender women of color, has been obscured by these other issues. A hopeful note has been the emerging recognition of the importance of data in documenting these concerns.

You have been one of the pioneers in trans-related data collection. The results of this work have been foundational in laying the groundwork for what we know about a number of trans communities. Can you share what first got you interested in this kind of work and why you think it is so important?

Back in the 90s, I spent a good deal of my time in DC, where I encountered many transgender women of color who were living hellish lives. Too many were dying from violence, HIV, substance abuse, homelessness, and despair, and they were not being served by the district government’s health care and social service agencies. This was a time when trans people were not well understood, and the social stigma drove too many cisgender people to act out horrific violence. The galvanizing moment was the tragic death of Tyra Hunter, a transgender woman who was denied medical care by the DC Fire Department and DC General Hospital after a car accident in 1995. She died on a gurney untreated by the ER staff, and her mother sued for gross violation of her child’s civil rights. She was awarded $2 million by a jury. Transphobia is tragic, but it also can be very expensive to taxpayers.

I knew of a transgender survey that was conducted in Philadelphia[3] by a group of friends and saw that putting hard facts and figures on paper about a “hidden” population would be a powerful advocacy tool to inform the DC government of the many unmet needs and sheer human misery. So the Washington Transgender Needs Assessment Survey (or WTNAS, pronounced “witness”) was born. I followed the Philadelphia survey’s first-time use of the two-step method of asking respondents about their gender followed by their birth sex. Since many transgender people will simply identify themselves as male or female after their transitions, this methodology captured more trans people than just asking a single question. In a little over four months, WTNAS had 252 trans and intersex people in its sample. It was also the first survey I know of in the United States that was translated into Spanish.

After the report[4] was released, the DC Department of Health provided the first trans-specific HIV-prevention funds, and a few years later, Transgender Health Empowerment was founded, the first transgender community-based organization in DC. But perhaps more importantly, conducting the WTNAS study by following a community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach organized the transgender community of Washington, bringing all the diverse subpopulations together to work in common cause. It literally created our community.

You are currently working with the This Great New Community Survey in Virginia, among the first to directly target not just transgender individuals but also those who identify as gender nonconforming as well. You have also done work specifically with transgender people of color. Can you talk a bit about why you think it is important that surveys, and other research and activism, begin to more properly nuance their work with the trans population in this way?

Although “TGNC” is widely used in the same way we say “LGBT,” in a public health context, I view the trans and gender-nonconforming (GNC) populations as distinct with some overlapping needs and concerns. They are also very diverse, with many people of color, and they express their genders (or the lack thereof) in myriad ways. This impacts how and what kind of health care they seek, and indeed, how they view their bodies and their health itself. I’ve read that some gender non-binary people will adopt a trans identity in order to obtain access to trans health services, in order to partially virilize or feminize their bodies. Health care and social service providers and staff are largely unprepared to deal with them respectfully and comprehensively, and we have no idea of their sexual risks, their mental health and substance use, and other health conditions. Despite the lack of systematic surveillance by the CDC, transgender women of color are horribly impacted by the HIV epidemic. Even the CDC estimates that half of African American transwomen are living with HIV.[5] Trans-latinas also have high HIV infection. While these transwomen of color have some terrific advocates, they also need allies to speak truth to power where their voices can’t reach.

The ability to be recognized, legally, for who you are is a foundational human right, and yet it is one that is denied to many trans people. Why do you feel it is important that people be allowed to receive legal recognition for their chosen gender identity?

In a fundamental way, recognition of chosen gender is more important than marriage equality. The latter validates the legal recognition of someone’s love and family, but gender goes to the heart of what it means to be a human being. Denial of someone’s gender is to deny their personhood, agency, and existence. Traditionally, legal recognition of a trans person’s gender could only be obtained with documentation of sex-reassignment surgery. Although the insurance industry is finally beginning to cover the costs of transgender health and even the surgeries, many trans people do not have insurance and cannot afford the out-of-pocket costs. But perhaps more importantly, many trans and gender-non-binary people do not want these surgeries. After they socially transition, their identities are grounded in their lived experience, not their birth anatomy. Gender (binary, non-binary, or the total lack of it) is a personal expression of one’s humanity, and it must be respected. Full stop.

One of the central issues of trans activism in recent years has centered around bathrooms. So-called bathroom bills have become a lightning rod for drawing attention to the discrimination faced by many trans people. Why do you think this is so?

This is sheer hysteria—fear-mongering used by social conservatives as a wedge issue for political gain. I like to say the controversy shows that trans people don’t even have a pot to pee in. But it is also illustrative of how these conservatives strive to maintain the social stigma of being transgender. Stigma has been heavily researched in the social sciences, but really it’s just a means for many, if not most people, to safely hate others who are different from them. I’m sure many of my generation remember the “Hate is Not a Family Value” bumper sticker. Oh, but it is. In these socially and politically polarized times, hatred has become a central organizing principle of society: you are defined by who you hate. That’s what I call the false empowerment by scapegoating others—blaming someone else means you don’t have to deal with your own shit. So the maintenance of stigma becomes a means of escaping not just the notice of personal deficits but also the lack of accountability for one’s actions toward themselves and the lack of responsibility toward others. Whether we accept it or not, the simple truth is that we are all spiritual beings sharing a human experience that intrinsically links us together on this fragile orb we are so busy destroying.

Given your years of activism and involvement, what do you think should be the main focus of the trans-rights movement in the United States today?

Probably inclusion in, and passage of, the Equality Act. Anti-LGBTQ discrimination disproportionately affects trans and GNC people because so many lack passing privilege, the ability to pass as cisgender/straight. A job is more than just income—it’s a chance at a normal life. But for everyone living today and the next generations to come, we must do something to halt the effects of man-made climate change. According to the UN, we’ve got just a dozen years before we reach the tipping point, when there’s nothing left to do except adapt to extreme weather, droughts, famines, water shortages, and widespread tropical diseases. I’d say the survival of the species, straight and gay, cis and trans, should properly be our first concern in the United States and everywhere else.

The Trump administration has received various, mostly well-deserved, scathing critiques for their approach to trans-related policies, which many view as a reversal of the more positive directions taken by the Obama administration. That said, the current policies either being put in place or rescinded do not move overall policy to a place that differs from the early years of the Obama administration or, in fact, from any previous administration before that. Why do you think such ire is being directed specifically at the current administration?

The national LGBT organizations fought hard during the Obama administration to obtain open service for trans service members and also to enforce the US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission’s finding that trans people are protected from discrimination under Title 7 of the Civil Rights Act. The Affordable Care Act also prohibited discrimination in health care on the basis of gender identity, and the federal government began taking its first steps to collect data to finally count transgender people in some of its national health care surveys. These were not gimmies. We fought long and hard to move people—lots of risk-averse bureaucrats and some who were religious fundamentalists—to achieve these rights. So losing these gains has been jarring and yet another reminder of our vulnerability as trans people living in an intolerant culture.

I am a survivor of physical violence including a murder attempt, and I understand transphobia all too well. I’ve had to become a student of stigma in order to survive, but still, transphobia strikes me as odd. Not so long ago, in non-Western cultures, we trans people were valued as healers and teachers, for only we truly understood the twin mysteries of human existence: male and female. A pearl without price, to be sure, that today is sadly cast before and trod under by swine.

As someone who has been a trans-rights activist for nearly three decades, what do you see as the future of the trans-rights movement in the United States?

It’s hard to predict what might happen to a small, under-resourced movement representing a still-stigmatized population attempting to survive while living under an unpredictable administration led by people who use fear as a motivator for their supporters. But I’ve told my friends in the HIV and trans-health research world that we must continue to develop our interventions and to educate our health care and social service providers as best we can, so when political change inevitably comes, we will be ready to quickly implement those changes to improve the health and lives of trans and gender-non-binary people. But in the meantime, it’s Bette Davis’s famous line from All About Eve: “Fasten your seat belts, it’s going to be a bumpy night.”

References:

[1] Sandy Stone, The “Empire” Strikes Back: A Posttranssexual Manifesto (University of Texas at Austin, 1993), [PDF file], http://webs.ucm.es/info/rqtr/biblioteca/Transexualidad/trans%20manifesto.pdf.

[2] Jessica Xavier, “Transsexual Feminism and Transgender Politicization,” TransSisters: The Journal of Transsexual Feminism, no. 10 (1995), https://learningtrans.files.wordpress.com/2010/11/transsexualfeminismtransgenderpoliticization1.pdf.

[3] T.B. Singer, M. Cochran , and R. Adamec, Final Report by the Transgender Health Action Coalition (THAC) to the Philadelphia Foundation Legacy Fund (for the Needs Assessment Survey Project) (Philadelphia: Transgender Health Action Coalition, 31 October 1997).

[4] Jessica M. Xavier, The Washington DC Transgender Needs Assessment Survey: Final Report for Phase Two (Administration for HIV and AIDS, Government of the District of Columbia, August 2000) [PDF file],

[5] Jeffrey H. Herbst et al., “Estimating HIV Prevalence and Risk Behaviors of Transgender Persons in the United States: A Systematic Review,” AIDS and Behavior 12, no. 1 (2008): 1–17.