On the cusp of President Biden’s time in office, the temptation to look forward to what the Biden administration will be able to accomplish is irresistible. I want to think about Covid-19 vaccine rollouts, qualified and diverse cabinet nominees, and policies that will move towards dismantling white supremacy. Instead, though, I am left looking backward at what has been lost in this election cycle, and what must be rebuilt.

I was 16 years old the last time I had a strong faith in American democracy. My American history teacher instilled in us a positive sense of American exceptionalism using the beloved narratives of the remarkable foresight of the founding fathers, of George Washington returning to his farm, and of the “shining city upon a hill.” My West Wing-inspired choice of summer camps took me to Georgetown to study American politics and run a mock election. I wasn’t entirely blind to the darker parts of America’s past, but I was resolute in my patriotic belief in the American political system and my future career in elected office.

At 30, I have re-learned American history without the rose-colored glasses and with an understanding of systems of oppression. I see my 16-year-old self as naïve. I still see beauty in the ideals of equality and opportunity, but when it comes to reality I tell people what I appreciate most about America is its national parks.

My partner saw things differently. I first thought his belief in American exceptionalism verged on blind optimism. He grew up in India, so I attributed his appreciation of the U.S. to the after-effects of growing up on American television—the ultimate soft power. He isn’t blindly optimistic, though. He had identified failings in the Indian democratic system while I was still convinced that a career in politics was my dream. He just believed in the resilience of American institutions.

“This country,” my partner always says appreciatively when we are out driving, especially where I-93 curves through the mountains in New Hampshire. He has a fervor for this place he has made his home, an exceptional America.

That has made the 2020 presidential election, from the partisan lead-up to the violent aftermath, so much harder for him than it has been on me. I came into this election year expecting it to reinforce my cynicism about America. My partner, though not American, came into it with a greater belief in American institutions and a greater apprehensiveness at the prospect of their decline. He had a genuine hope that the election would reaffirm his positive view of the U.S., a hope that has now been dashed.

While we watched the debates, I showed him the letters that previous presidents have left for their successors. This ultimate display of bipartisanship and patriotic unity soothed both of our nerves, but I wasn’t holding out hope for an encouraging letter left in the Oval Office this January 20.

As election results trickled in with no end in sight, he decided to learn about the history of concession speeches. Once it became clear that President Trump had lost but would not concede, my partner’s disappointment in the failure of American norms was palpable. He saw the lack of a concession speech, or even a concession, as an erosion of what makes America beautiful. It’s a far cry from President Washington returning to his farm.

I was more resigned than disappointed. In the face of my resigned cynicism, my partner held onto his belief that America was just exceptional enough to get out of this mess. He believed that in most other countries, a figure like Trump would have done more damage. He believed that the foundational adherence to democratic values had been shaken, but not shattered. His eyes were bright as we watched the acceptance speeches, because he saw our future children in Vice President Harris and because he hoped that Biden would be able to provide the necessary “time to heal.”

He pointed out that American democracy works because it has always worked. Even without certain norms and with startling doubts about the election’s validity from Republican voters, continuity will maintain the integrity of our democracy.

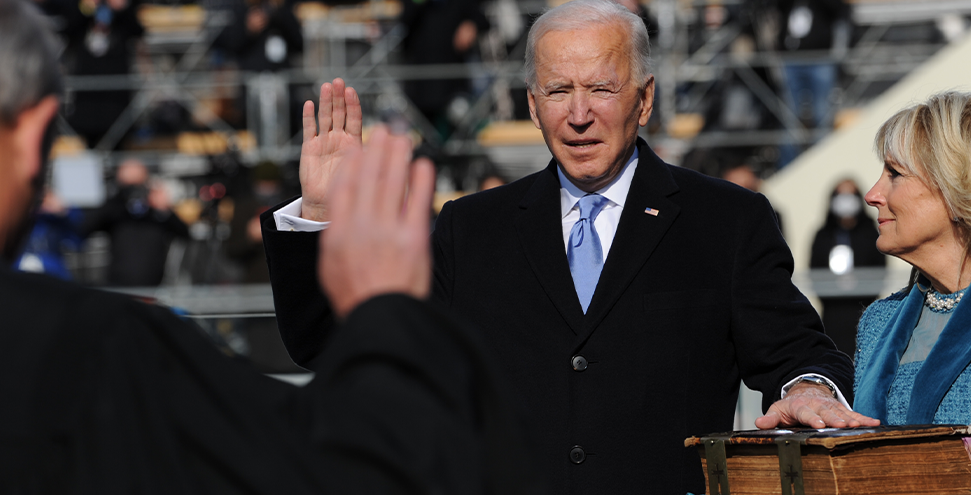

On January 6, America proved that it isn’t exceptional. At worst, it experienced an attempted coup—at best, a seditious riot. President Biden himself acknowledged the fragility of our democracy. The best we can hope for today is a long and arduous rebuilding of the norms and institutions underlying American democracy.

Thanks to Trump’s insistence that he didn’t actually lose the election, the foundation of our democracy is gone. Too many Americans have lost sight of what democracy is: counted votes, decided elections, and the peaceful and gracious transfer of power.

“We had an election that was stolen from us,” Trump said to his supporters.

He’s wrong about what was stolen.

False cries of fraud, leading to the violent aftermath of the election, have stolen the exceptional America so many, including my partner, believed in. Our institutions have been undermined, our norms have been dismissed, and our processes have been ignored. We both hope that American democracy can be rebuilt, reclaimed, and reinforced. But in our minds, American exceptionalism is gone forever.