As I was completing my MPP, a faculty member at Harvard Kennedy School had written to the chair of a prominent North American foundation, confident they would be interested in my work. The chair, a man of South Asian descent whom I shall call Mr. X, sent back a pat response: The proposal focusing on stories around gendered violence in Punjab failed “dispassionate assessment,” his email said, since “there are no cases and not even any mention of rapes against women related to that violence.”

To Mr. X, I owe many thanks. Peeved, my feminist curiosity [further] piqued, I spent the next several years in conversations that repeatedly destroyed his cocksure reply.

Mr. X had further advised, in a hurried attempt to quickly invalidate interest in another major conflict and human tragedy of modern South Asia: “Unlike Punjab, there were some rapes in Kashmir. … However, it is exceedingly difficult and quite sensitive to get anyone, including the victims themselves, to discuss these cases.”

Indeed, when approached by tourists, these regions of complicated (re)colonialisms, conquests, and consequences remain indifferently docile; when approached with care and compassion, they begin to share the past and present.

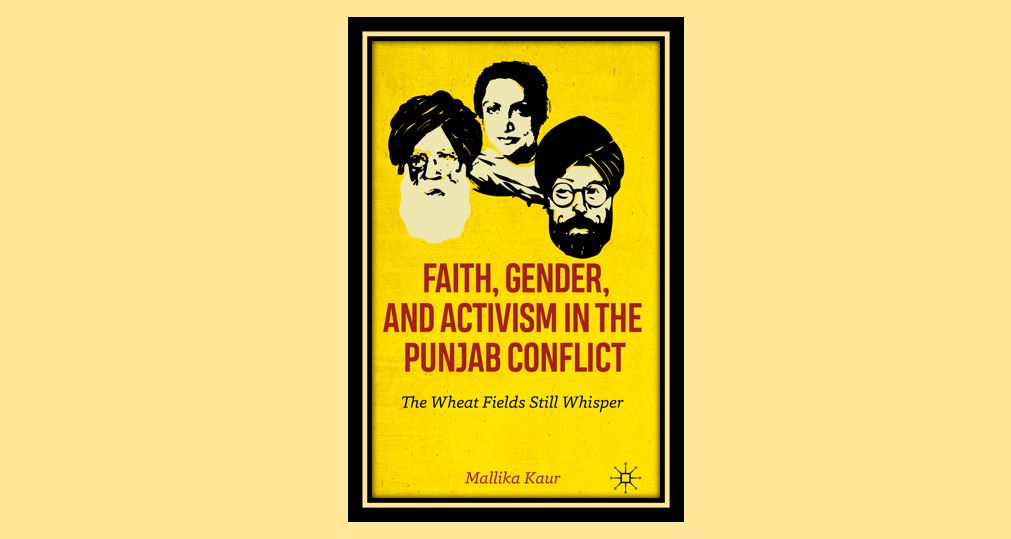

In my new book, Faith, Gender and Activism in the Punjab Conflict: The Wheat Fields Still Whisper (Palgrave, 2019), I attempt to capture how the conflicted past continues to live on, how Punjab continues to rustle with the stories that women & communities supposedly don’t want to tell.

Punjab was made a laboratory of postcolonial India’s nation-building project and subjected to a series of top-down experimentations: consolidation (with new post-British borders, 1947); provision (Green Revolution agrarian experiments, 1950s–1960s); and discipline (military and policing operations, 1980s–1990s). Sikhs, 2 percent of India, first constituted 33 percent of Punjab, and then after a redrawing of borders by New Delhi, 56 percent of Punjab, with Hindus, the majority religion in India, at a close second. Today Punjab is 58 percent Sikh and 38 percent Hindu.

It was exactly 36 years ago, during a blistering June, that Punjab forever changed, again.

By 1984, Sikhs —a faith community founded 500 years ago and often visually identified by flowing hair, beards, turbans—found themselves socially and politically alienated.

In June 1984, Sikh gurdwaras—sites of prayer and gathering—across Punjab were attacked in a coordinated Army assault. Thousands of Sikhs (trapped gurdwara-goers on one of the most significant holidays in Sikh culture, as well as civilians inside vulnerable nearby homes, or those outside, daring to transgress the curfew to gather life-necessities, or to offer aid to the injured, or to march in resistance as plumes rose from centuries-old gurdwaras) were massacred. A few hundred armed Sikh fighters, who had been used as the pretext for the attack, died in the firefight with the Indian Army, 100,000 of whom now occupied Punjab under New Delhi’s orders. I resist referring to the June 1984 attack by its Army codename “Operation Bluestar” because to use this sanitized label is to perpetuate a one-sided justificatory narrative about the Punjab of the 1980s.

In the ‘mainstream’ Indian imagination of the armed conflict that corroded Punjab in the decade after June 1984, the men involved (as militants, separatists, and political leaders) are seen as irrational actors with monstrous tendencies. The women continue to be cast as vulnerable and victimized, but hardly ever as organizers, protestors, videographers, champions of rights.

Baljit Kaur, one of the human rights defenders featured through the book explains how she quit her Air France office job in 1985, immersing herself entirely in human rights advocacy work. She used her last gratis ticket to visit Amnesty International in the U.K. and Asia Watch in the U.S.A., armed with rare video footage she had recorded of the scorched Punjabi countryside, where rule of law was officially paused —through a series of extraordinary and extralegal measures. “I had been keeping very busy with documentation activities across Punjab in the immediate aftermath. No one stopped me after June 1984. Maybe they thought I was headstrong, and foolhardy, but in all my undertakings, I was never actively stopped by relatives,” says Kaur [no blood relation to author; Sikh women have been bequeathed a common last name since 1699]. The octogenarian always makes a hard distinction between societal custom, expectations, gossip, even ostracism, and active curtailment. Like the other human rights defenders I spoke with, June 1984 changed her life and work.

Of course, within an already marginalized conflict (suppressed and forgotten though up to 250,000 people died), the voices of women were and are further marginalized. In Chapter 3, I recount a story from a jail letter written by a woman transferred from one secret torture center to another in the mid-1990s:

Gurpreet Kaur, from Shafipur, near Tarn Taran—I can never forget. Her only crime? She was the wife of militant Baljinder Singh, with whom she had spent like fifteen days. She was picked up and kept in illegal custody for eight months. Then, she had run away from custody with another woman, only to be caught again. She now attempted suicide by taking some pills. … She was all pukey and dying when the police threw her in my cell. I cared for her. After two days, she was feeling better. […]

DSP and Inspector CIA Bhikivind, Ravi Bhushan, came for Gurpreet. … And that was the end. She had told me that she knew she would die …her only hope was not to be touched by male police. When she was taken, there was no female constable with them.” [p.78]

Mr. X of course wouldn’t find this account explicit enough. Gurpreet’s former cell mate refuses to kowtow to desires for torture porn or trauma voyeurism: she thus affords dignity to the unreparated victims of Punjab. The lessons I have learnt from her and other interlocutors are not presented as prescriptions in the book. The readers may draw their own lessons and conclusions, once the stories are allowed to speak for themselves.

I grew up in Punjab in the 1980s and 1990s among the middle and upper class of Sikhs, most of whom read their censored news in English, suppressed thoughts in Punjabi, and spent all means necessary to appear unaffected. Later, as a newly minted lawyer in the United States, the need for South Asia to have its own regional Human Rights Court or Commission consumed me. But my work soon made me increasingly intrigued by people’s stories that remain largely unwritten and unexplored, yet deeply inform everyday realities. How ordinary people choose to define or end one another’s stories is vital, especially where a culture is not truly textually mediated or even institutionally mediated, least of all during emergencies. How neighbors understand each other’s distinct life stories has often determined the difference between harbor and harm. Where prevailing wisdom has rendered certain historical facts as fictions, and certain identities as suspect, stories may begin to darn even the most frayed social fabric.

Internal armed conflicts across the world share in common the unpredictability of seemingly mundane issues turning the tides of allegiance, the reliance on petty bureaucrats, the steadfast banality of evil, and the shameless obligations thrust on targeted peoples: to speak in unison and tell a linear story, subjected to the strictest scrutiny. Meanwhile, the state may present absurdities that media reports repeat and with which we must contend. Seeming delusions and divisions among Sikhs have provided another convenient reason for New Delhi and many Indians to eschew meaningful engagement with Punjab. Instead of continuing to try to understand Punjab’s history from a defensive position, I decided to investigate: In Punjab, with its rich legacy of resisting oppression, how did the human rights defenders and citizen-activists respond?

Today in 2020, when India struggles with delivering on its Constitution’s textual promises of becoming a socialist democratic republic—in the face of its poor being criminalized and starved during COVID lockdowns and its minorities and dissenters being targeted, jailed, maimed, lynched—it might have been assumed that lessons from the Punjab disaster would be in the spotlight. However, the entrenched views on Punjab’s recent history have traveled far beyond its borders.

One of the key drivers of this project for me was exploring: In our world at once riveted and recoiled by violence, what might shift in our collective understanding and action if we spent nearly as much time fascinated by the stories of everyday people and unarmed human rights defenders as we are by the eroticism of violence and romanticism of armed resistance? This book attempts to ensure that lessons drawn from the actions of human rights defenders during Punjab’s unaddressed conflict years, spurred by the Army Assault ordered by Prime Minister Indira Gandhi in June 1984, travel outside Punjab’s borders to provide hopeful blueprints for citizen-activists, scholars, and policy makers. Today, when the authority and ability of an “international community” is repeatedly embarrassed by the world’s conflicts, experts and affected citizens alike note the need for local models that can truly bring human rights home. The blueprints for indigenous approaches may in fact lie in conflicts that have thus far been marginalized internationally, by one Mr. X at a time.

Mallika Kaur is a lawyer, writer, educator who focuses on international human rights with a specialization in gender and minority issues. Kaur received her Master in Public Policy from Harvard in 2010 and JD from UC Berkeley Law School, where she is currently a Lecturer and teaches skills-based and experiential social justice classes.

Edited by: Derrick Flakoll

Photo courtesy of the author; cover by Bilas Design.