BY FUAD HUSEYNOV

The World Bank estimates the current demand for infrastructure investment in emerging and developing countries at above $1 trillion a year as of 2015. Meanwhile, the Asian Development Bank estimates a need for almost $169 billion in Central Asia alone from 2010-2020, of which $92 billion is needed for the development of new infrastructure.

During the last century in most of the developed world, governments have been the main funding source for infrastructure projects. However, due to budgetary constraints and growing infrastructure demands, the private sector gradually increased its share in infrastructure finance through various project finance tools.

In Central Asian countries of the former Soviet Union—Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyz Republic, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan—infrastructure projects traditionally followed a centrally-controlled model whereby most of the infrastructure was designed to operate as a public good (i.e. operating free of charge or for a minimal fee). However, after the collapse of the USSR, newly independent states faced immense challenges with transitioning from being part of a unified federation to becoming sovereign states responsible for their own national infrastructure and economies. The region inherited from the Soviet Union is a failing infrastructure network, with most of the road and energy lines linked to Russia’s own infrastructure.

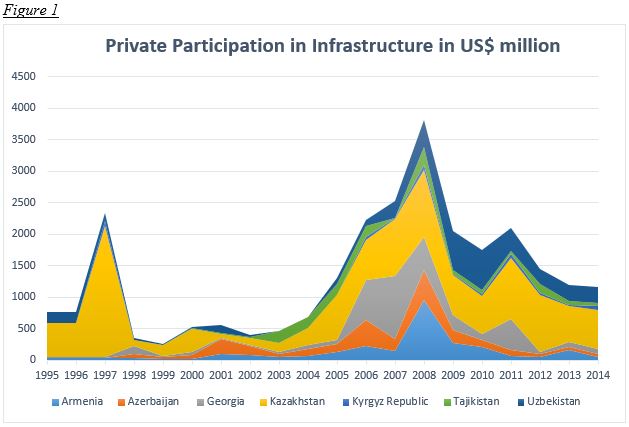

Moreover, these economically depressed and newly independent states lacked the technological know-how and financial resources for infrastructure development, which made them inclined to open up doors to multinationals and international private firms. Although private sector investment in infrastructure rose between 1998-2008, there has been a substantial decline for all countries in Central Asia since the global financial crisis (see Figure 1). The growth in the region has hit a two-decade low due to the recent drop in commodity prices. As a result, governments of oil exporting and importing countries in Central Asia that traditionally spurred economic growth through expansive public spending will be unable to meet the demands of the immense infrastructure financing gaps.

Current economic trends in Central Asia

According to the IMF, three major factors affect slowing economic growth in Central Asia: large and sustained decline in commodity prices, wide-ranging spillovers from Russia’s recession, and the slowdown and rebalancing of China’s economy.

The sudden drop in oil prices from above $100 per barrel to below $35 per barrel between 2014-2015 significantly affected the export revenues of oil exporting countries—Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan—and together they face a 1.1 percent average GDP growth rate, down from 3.2 percent in 2015.

Meanwhile, oil importers—Armenia, Georgia, the Kyrgyz Republic and Tajikistan—are hit by their close linkages to Russia through trading and remittances, leading to a slowing growth rate of 2.6 percent in 2016, down from 3 percent in 2015. Low demand from China and a decline in price of other non-oil commodities (copper, aluminum, cotton) also continue to hurt export revenues of Central Asian countries.

Although Central Asian states have increased their fiscal stimulus to support economic activity, expanding budget deficits and sustained economic headwinds will require fiscal consolidation in the near future. Faced with gloomy growth projections and shrinking budgets, the governments of Central Asian countries need to find alternative methods to finance their growing infrastructure needs.

How Public-Private Partnerships Could Help

Using public-private partnerships (PPPs) as a financing mechanism can help Central Asian governments to attract private sector funds to infrastructure projects. They can also be a handy tool to address agency problems, ensure efficient risk sharing, identify potentially successful projects, and establish effective project monitoring schemes.

In large infrastructure projects, which involve several stakeholders, agency problems often arise from differing interests of the various parties. This issue can be mitigated, to some extent, by an appropriate financial structure, such as a PPP modality. For instance, a construction company with a financial stake in the project and/or a contractual obligation for future maintenance of the asset will have a greater incentive to deliver a quality project than a company involved during only the construction phase. Through PPPs, Central Asian governments, which often lack resources and sophisticated knowledge to ensure the quality of large scales projects, can better distribute risks presented by the project among multiple parties.

Since most PPP projects are financed through bank loans, the concentrated ownership of bank debt encourages lenders to devote considerable resources to evaluating projects and monitor the progress. By tendering infrastructure projects through a PPP modality, Central Asian governments will be able to disqualify poorly selected infrastructure solutions at an early stage, as they will see little or no interest from lenders. At the same time, by establishing Special Purpose Vehicles (SPV) (i.e. a new joint company established by the consortium of companies participating in the project), governments can finance the project through borrowing locally and internationally and better ensure external monitoring of project activities. SPVs also provide an opportunity to isolate the debt in the project company in case sponsors are reluctant to participate in the project due to possible high bankruptcy costs that may damage their business. In case of project failure the project company may claim bankruptcy, which will not appear in the sponsor’s balance sheet hence won’t reduce the operating value of their business.

Finally, a bankable PPP project can be an attractive investment option both for local and international banks, as well as infrastructure development companies that could participate in the enterprise through equity investments. Since capital markets often share risks better than the tax system, the cost of capital for corporations could end up being lower than for governments. Ultimately, carefully designed PPP projects can significantly ease the financial burden of Central Asian governments and help address other problems in regional infrastructure development.

PPP environment in Central Asia

The Infrascope—a methodology developed by the Inter-American Development Bank, Asian Development Bank, and the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) that derives the so-called ‘PPP readiness index’—assesses countries’ readiness and capacity to implement sustainable, long-term PPP projects.

While the 2014 Infrascope covers only Armenia, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyz Republic, Tajikistan from Central Asia it reveals several persistent problems facing the region. These include: the lack of a proper legal framework, non-transparent tariff setting mechanisms, low utility bill collection rates, and non-existent or incapable governmental bodies dedicated to PPP promotion. For example, when it comes to PPP environment, Armenia lacks strong safeguards for public and private sector participants, Georgia suffers from inadequate concession law, weak coordination and oversight, and the Kyrgyz Republic possesses limited institutional capacity and an uncertain business climate that lowers the appetite for private sector investment.

Nevertheless, there are some promising developments in the region. For example, Kazakhstan adopted a new PPP law in 2015, which created a common legal framework to regulate public-private partnership projects. Moreover, the country’s PPP Center is the only official body in the region that promotes and overlooks PPP projects. Azerbaijan also recently adopted a new law that introduces options for potential financing of Build-Operate-Transfer (BOT) projects. Building on these small gains is essential for overcoming current hurdles to private investment in infrastructure projects.

Policy Recommendations

Currently, there exists a Washington Consensus-based list of major policy reforms that are necessary to boost private participation in infrastructure projects. These include: establishing a legal and regulatory framework for concession projects, creating institutions that will prepare, award and oversee projects, enforcing legislation through a functioning court system, improving the overall business, political, and social environment for investment, and having the necessary financing facilities to fund infrastructure.

However, given the relative newness of PPP as a concept in the region and the traditional approach to infrastructure as a public good (i.e. providing the population a social benefit rather than a return generating asset), the potential for PPPs still remains unexplored. The policy dialogue with governments in Central Asia should start by changing this archaic mindset, which will enhance governments’ capacity to undertake PPP projects.

In addition, Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) need to capitalize on the momentum of regional economic downturn to motivate political will and guide the Central Asian states towards establishing dedicated governmental units for PPPs that include hard targets for infrastructure project financing within annual government spending.

Newly established governmental units would provide an essential counterpart for many international entities dealing with PPPs. In turn, these units could create the institutional capacity and knowledge to be able to justify reforms, identify good projects and conduct cost-benefit analyses for capital investments using public funds. Setting hard targets for PPP projects will enable these newly established units to adopt the necessary policies to attract private investment and steer the government towards more of a profit-generating mindset that still serves the public good.

Of course, PPPs are not a silver bullet, but they can help address many of the issues systemic to the region in the field of infrastructure development. Ultimately, by expanding investment in infrastructure, Central Asia can better position itself for sustained economic growth and prosperity in the coming decades.

Fuad Huseynov is a 2015 graduate of the Mid-Career Master of Pubic Administration Program at the Harvard Kennedy School. He was also the Mason fellow from Azerbaijan. During his career, Fuad managed large scale projects at the UN and the EU. In his capacity of department director at the Central Bank of Azerbaijan he was the government counterpart of the multilateral development banks for major development projects in the country. Fuad has recently joined the Islamic Development Bank in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

Photo by Asian Development Bank via Flickr.