This article was originally published in the 2012 edition of the Kennedy School Review.

Entering 2012, the world finds itself in a precarious financial position. In January of this year, the World Bank released its new economic outlook, warning of a global, double-dip recession. “An escalation of the crisis would spare no one,” Andrew Burns, manager of global macroeconomics and lead author of the World Bank report stated in a press release, matter-of-factly, before continuing: “Developed- and developing-country growth rates could fall by as much or more than in 2008/09. The importance of contingency planning cannot be stressed enough” (World Bank 2012). The report lists several key risk factors, including the sovereign debt crisis in Europe; the global spread of risk aversion resulting from the European crisis; and stifled economic growth resulting from inflation-motivated tightening of monetary policy in developing countries.

But the World Bank may have forgotten a critical fourth concern: the snail-paced economic recovery of the world’s leading generator of global demand and output—the United States. The United States still faces constrained economic growth and an unemployment rate of 8.5 percent, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. With an already expanded U.S. money supply and all-time low interest rates, monetary policy is no longer an effective tool—even in the short term—to stimulate growth. Meanwhile, record high debt levels and a self-imposed debt ceiling have severely limited the possibility of any fiscal expansion funded by borrowing.

How then can the U.S. government expedite a recovery? I propose a new form of fiscal stimulus, financed by future-flow tax credits rather than government borrowing. Similar tax credit programs have been used on a small scale to promote low-income real estate development and small business investing. I suggest a large-scale, federal stimulus plan that is financed in a similar manner—as a budget-neutral engine of job creation.

Future-Flow Tax Credits: A Smart Alternative Stimulus

Many prominent economists argue that stimulating small and medium-sized business employment is critical to rehabilitating the U.S. economy. During the past two decades, small and medium-sized businesses have been the workhorse of U.S. economic growth, accounting for more than 65 percent of net jobs added (U.S. Small Business Administration n.d.). Recognizing the importance of small businesses, the Obama administration created Startup America in 2011 to provide resources to entrepreneurs and, in January 2012, elevated the Small Business Administration (SBA) administrator to a cabinet-level post.

Such approaches are not without their problems. Josh Lerner, Harvard Business School professor and venture capital expert, highlights a core concern with many state-sponsored funds that invest in small businesses: the funding tends to be managed by politicians who direct capital to politically convenient investment opportunities (Lerner 2009). This results, almost inevitably, in poorly performing funds and an inefficient and corrupt allocation of public capital. For example, a late 2011 Republican presidential primary debate revealed that 47 percent of investments from the state-run Texas Enterprise Fund went to companies affiliated with Texas Governor Rick Perry’s political donors.

One solution, already implemented in several small investment programs, is the creation of public-private partnerships. In such partnerships, the government incentivizes authorized private investment funds, which bring investment expertise, to raise and place capital in underinvested areas. The incentive comes through a tax credit match, paid out to fund managers over time, on the amount of capital raised and placed. (This mechanism explains the “future-flow tax credit” moniker.) By requiring investment within a certain time frame and in certain sectors or geographies, the government can effectively stimulate job creation in periods of illiquidity or risk aversion and in struggling areas or industries. By creating a floor on potential losses for fund investors, the tax credits improve the funds’ risk/reward profile in times of risk aversion. At the same time, fund managers retain a significant equity ownership in the investments, ensuring their incentive to make quality investments.

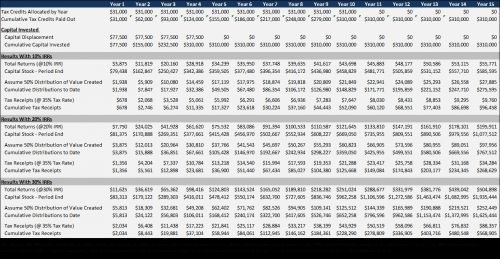

Compared with deficit-funded fiscal spending, future-flow tax credit programs do not increase public debt levels. In many current state-level initiatives, the government allocates the tax credits to authorized private funds over the course of ten years, yet requires the funds to invest the majority of the targeted capital within just a few years. This structure offers an expedited positive impact on business investment and job creation but a delayed impact (if any) on deficit levels. If investments are properly targeted to spur growth, increasing tax revenues can offset the delayed tax credits, yielding a neutral or even positive impact on public budgets (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 — Model of future cash flows and capital stock appreciation.

Another distinct advantage of tax credit–incentivized investment pools over traditional consumer stimulus programs (e.g., tax rebates) is that such investments fuel the capital stock appreciation necessary for longer-term economic growth. The job creation potential of consumer tax rebates fades within months of mailing the rebate checks. Similarly, while employer grant programs (when the government offers businesses a subsidy per job created) produce new jobs, employers often lay off the new workers after the minimum required duration to receive the subsidy. Tax credit–incentivized business investments spur longer-lasting jobs but carry the tradeoff of not having as immediate an effect as either tax rebates or employer subsidies. As such, if short-term growth is needed, future-flow tax credit programs should be used in combination with more direct consumer stimulus mechanisms.

CAPCOs and NMTCs: A Proven Track Record

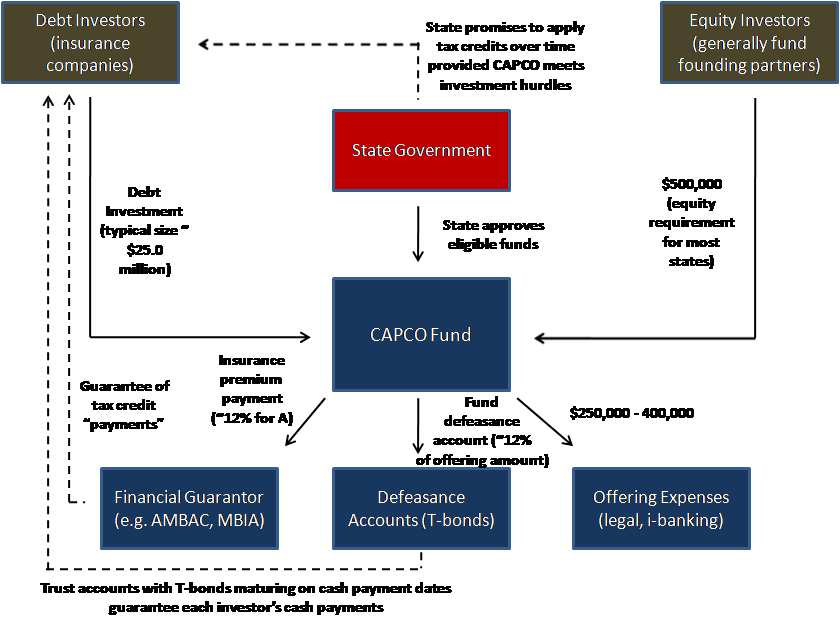

Certified Capital Companies (CAPCOs) are one of several prominent models of future-flow tax credit–subsidized investment funds currently in use in the United States. CAPCOs currently operate in the District of Columbia and seven U.S. states: New York, Texas, Louisiana, Florida, Missouri, Colorado, and Alabama. State governments offer certified CAPCOs a dollar-for-dollar tax credit match on the amount of capital raised and invested in small businesses. Some states target high-tech, venture investing by requiring that a minimum percentage of the capital be invested in high-tech startups. Others, such as New York and Louisiana, target economic development and job creation in rural or impoverished areas. State legislatures have decided to use a specific type of tax credit—insurance tax credits—as insurance companies are regulated and taxed by states, pay significant levels of state tax, and manage more investable capital than all other sectors except banking. To attract capital from risk-averse insurance companies, CAPCOs structure the government-provided tax credits into bonds, which are then insured by financial guarantors to raise the bonds’ credit quality to investment grade (see Figure 2). To date, the CAPCO model has raised and placed more than $3.5 billion in small business investments.

Figure 2 — CAPCO flows at fund closing.

Meanwhile, the federal New Market Tax Credits (NMTC) program has allocated more than $29.4 billion in capital to date, offering 39 cents on the dollar in federal tax credits for capital raised and invested in low-income census tracts throughout the United States. While the overwhelming majority of this financing has been invested in low-income real estate development, a limited amount of funding has also flowed into business investment. A panel of administrative judges chooses how to allocate NMTC tax credits to private funds, based on their past low-income investment experience, investment track record, and fund-raising track record. Unlike the CAPCO model, qualifying funds can only pass the tax credits through to equity investors, not insurance companies or other debt investors.

Taking the Model to Scale: A National Stimulus Plan

To surmount the inertia of current recovery efforts in light of record low interest rates and the federal debt ceiling, I propose a new, multibillion dollar, federal-level, future-flow tax credit program that builds on the success of the CAPCO and NMTC programs. This small business–focused stimulus program should take the following general form:

- Size: The brunt of investment funds should be allocated to low-tech, small businesses. I propose a program that garners $250 billion for general small business investment (in areas like retail, distribution, services), which would nearly triple SBA loan volume compared to the previous four years. This capital would be dedicated to filling the unfunded niche between higher-risk venture capital and lower-risk SBA loans, using both equity and debt funding. Given widespread concerns that risk aversion has also been hindering venture capital, I propose allocating an additional $60 billion to venture investing over four years, which would constitute a 30 percent to 50 percent increase in venture funding each year.

- Tax credit structure: I propose a 50 cent tax credit for every dollar of funds raised and invested by authorized fund managers. By offering an overly generous dollar-for-dollar tax credit match to a much smaller investor universe, CAPCO programs have been oversubscribed by up to eight times the available tax credits. While the 39 cents on the dollar NMTC program is also regularly oversubscribed, this fiscal stimulus plan is much larger in size, and a larger tax credit match may be necessary to incentivize absorption of the offering. The match level should be adjusted over time to reflect the changing supply and demand for credit. I suggest the credits be allocated over ten years, with the expectation that the diversified investments would yield typical long-term, small business returns of 20 percent to 30 percent, generating enough federal tax revenue to offset the tax credits. The tax credits should also be transferrable so as to increase their liquidity and value to investors.

- Investment requirements: I propose that certified funds be required to place 50 percent of the targeted capital within two years and 100 percent within four years. Further, the investments should take the form of five-year or longer maturity debt or equity to ensure that (1) the capital is kept in place long enough to fuel business growth and sustained job creation, and (2) short-term debt repayment does not bankrupt small, startup businesses.

- Choice of fund management: Tax credits should be allocated to venture and investment funds by the vote of an independent judging committee based upon prior venture and small business investing experience; prior investment track record and returns; prior capital raising experience; and commitment to invest in a tax credit–incentivized fund, if chosen. This model contrasts with that of CAPCOs, which allocates tax credits solely based upon funding commitments obtained and, therefore, results in CAPCOs with the best investor contacts, not the best investment track records, obtaining the majority of the tax credit allocation.

This future-flow federal tax credit program would offer an efficient, market-driven solution to provide fiscal stimulus and drive small business investment by leveraging private-sector expertise for public ends. Tax credit subsidies would help cure illiquidity, temporary risk aversion, and other job-inhibiting financial illnesses associated with the current economic slump. Further, by spurring small business investments today in exchange for credits tomorrow, the federal government could fuel sustained job growth without taking on additional debt. With monetary policy options exhausted and traditional fiscal options mired in politics, this innovative investment stimulus offers a viable means of surmounting our current economic hurdles.

Acknowledgements

Herein, I would like to acknowledge the direction and feedback provided by Professor Andrew Metrick (Yale University and Presidential Council of Economic Advisers).

References

Lerner, Josh. 2009. Boulevard of broken dreams. Princeton University Press.

U.S. Small Business Administration. n.d. Frequently asked questions: Advocacy small business statistics and research.

World Bank. 2012. World Bank projects global slowdown, with developing countries Impacted. Press release, 18 January.

William Werkmeister, a Midcareer student, is a concurrent degree candidate at the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University and the Yale School of Management. Prior to the Harvard Kennedy School, Werkmeister was an investment banking analyst with Salomon Smith Barney and a partner in two CAPCO venture funds. He currently serves as an advisory partner and board member to Calton Hill Capital Markets, a holding company of socially beneficial businesses.

Photo source here.