A preliminary version of this post originally appeared on the Ash Center’s Challenges to Democracy blog

Last year the City of Boston unveiled its plans to devote a portion of its capital budget towards a participatory budget, a social innovation that aims to reimagine citizen engagement, the appropriations process, and democratic participation. Specifically, Boston has apportioned $1 million of its capital budget towards a participatory budget that aims to engage and empower Bostonian youth across the city.

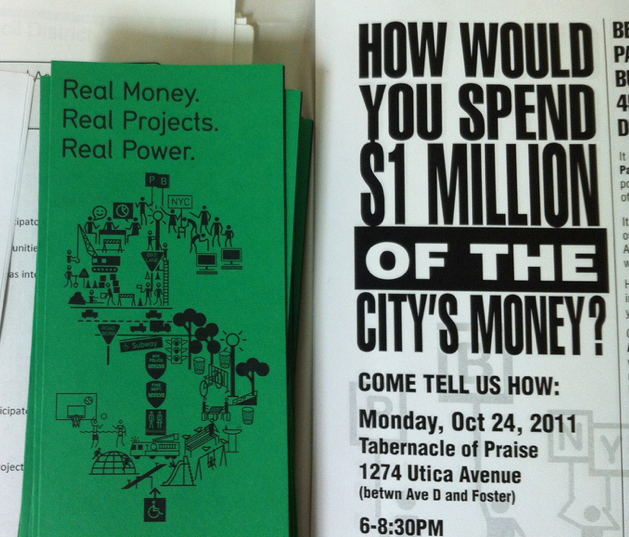

Participatory budgeting was first introduced in the city of Porto Alegre, Brazil in 1989, where as many as 50,000 people take part in the participatory process each year to decide on how to spend as much as 20% of the city’s annual capital budget. Since then, more than 1,500 cities have spearheaded participatory budgets across the globe, according to the Participatory Budget Project. While prolific throughout Latin America and Europe, participatory budgets are still in their infancy in the United States. Policymakers in just four cities – Chicago, New York City, St. Louis, and Vallejo – have administered participatory budgets at some point in the past decade.

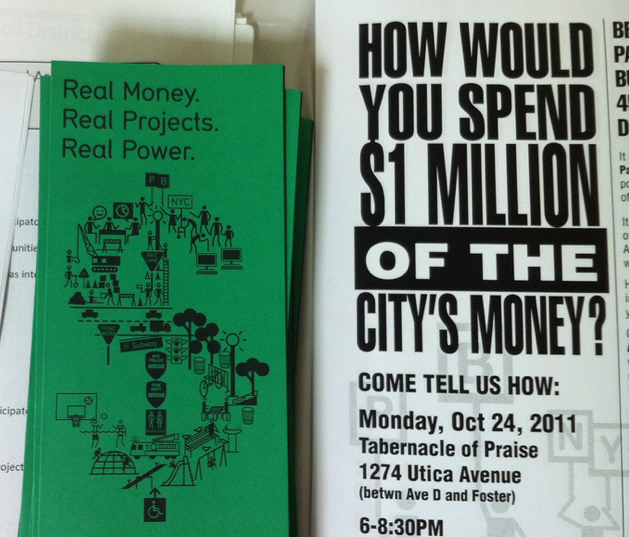

Participatory budgeting transforms the management of public money by flipping the traditional appropriations model on its head. Rather than a top-down approach, where city officials have complete control over capital outlays, participatory budgeting starts from the bottom-up, engaging with citizens who propose ideas and have complete deciding power on how they would like to see their taxpayer dollars spent. In doing so, participatory budgeting transforms the relationship between policymakers and the constituents they serve.

Participatory budget initiatives are usually comprised of five components. First, policymakers dedicate a pot of money from their operating or capital budgets for a participatory budget. Second, residents come together and form various committees that brainstorm ideas for how they would like to see the money spent. Third, citizen “budget delegates” develop proposals based on those ideas. Fourth, residents vote on proposals. Lastly, the government then implements the projects receiving the most votes.

The benefits of participatory budgeting flow in two directions. First, participatory budgeting changes the way citizens engage with their communities and government. Allowing constituents to make informed and fair decisions about spending and revenue empowers participants, builds trust between the government and citizens, and gives constituents a greater sense of agency in their neighborhoods. As Professor Archon Fung noted at a recent Kennedy School study group, participatory budgets usually result in “the thickening of civil society.”

Participatory budgeting not only changes how citizens see government, but also changes how government sees its citizens. It puts the constituent first, such that appropriators and budgeters — who are often removed from the process of deliberative democracy — rethink how their day-to-day work impacts citizens on the ground. The White House has even recognized the benefits of participatory budgeting, and recently signaled its support for participatory budgeting as part of its Open Government National Plan for Action

Last year the City of Boston set aside $1 million in its capital budget for a participatory budgeting initiative. This is the first time Boston—a city known for its novel forms of civic engagement and social innovation—will administer a participatory budget. With a capital budget of $1.8 billion, $1 million towards participatory budgeting may appear insignificant, but this small investment has huge potential for scalability.

Boston’s foray into participatory budgeting is unique, as Boston is the first city in the United States to administer its participatory budget initiative through its mayor’s office. Usually in the United States (and elsewhere), local council members tap into their discretionary funds to administer a participatory budget targeted to their jurisdiction and tailored to their constituents. Given the breadth of constituents he represents, administering participatory budgeting through Mayor Martin Walsh’s office may present some logistical challenges. At the same time, leading the initiative through the mayor’s office could ensure a broader impact on the Boston community.

Two ingredients are critical for a successful participatory budgeting initiative. First, you must have top-down political will from policymakers who authorize municipal funds. Perhaps more importantly, you must also have “bureaucratic will” from city officials who would otherwise appropriate those funds. This is certainly the case in Boston, where Former Mayor Menino, Mayor Walsh, and city officials in the Capital Budget Department remain committed to a successful participatory budget implementation.

Second, a successful participatory budgeting initiative requires genuine community involvement from the bottom-up. From steering committee meetings to assemblies where the ideation process takes place, the youth spearheading the participatory budgeting process remain engaged and excited to be part of this project.

In its first months, Boston’s experiment with participatory budgeting has generated excitement among community members and civic innovators throughout the country. Still, a number of questions remain regarding the effectiveness and efficacy of the initiative. For example, how will city officials measure the outcomes of interest such as citizen engagement, knowledge of municipal government, trust in government, and future community involvement? Counterfactually, what would the $1 million have gone toward had the city not engaged in participatory budgeting with the city’s youth? These are just some of the questions with which the city is grappling.

If successful, the City of Boston expects to increase its investments in participatory budgeting initiatives, realizing even greater returns in civic engagement and the deepening of democracy. By targeting youth specifically, this initiative will serve as a guidepost for state and local governments — such as Vallejo, CA — seeking to engage youth through a participatory budget framework. Most importantly, Boston’s participatory budgeting initiative will serve as yet another example of municipal governments using participatory budgeting to transform the relationship between the government and the governed.

Photo Source here.