Some Harvard Kennedy School professors are in need of remedial training in the theory and practice of teaching and learning. This is the clear and concerning take-away from the recent analysis of course evaluations carried out by the HKS Progressive Caucus.

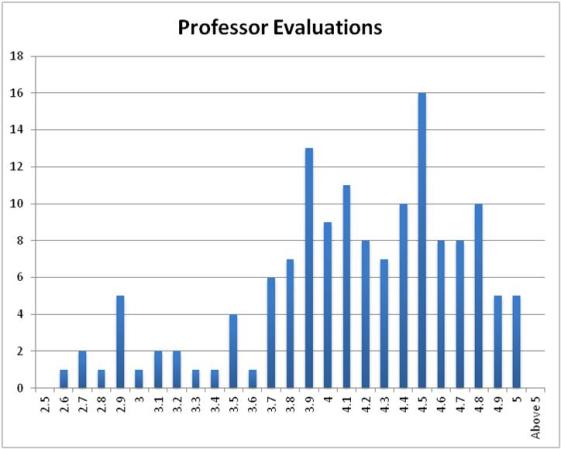

Although the majority of our professors receive comfortable scores of 4 out of 5 or above, there is a long tail of poor performance. Last year, 20 professors involved in 31 courses received a score of less than 3.5 and as low as 2.6 (only considering classes of ten or more students). That’s one in seven.

While a high school teacher must have a degree in education, the minimum requirement to teach at HKS is research ability or experience in public service. There is currently no required training in teaching at HKS other than a two-day workshop for new professors. It would seem, therefore, that required remedial classes in teaching would be a powerful step forward, but it is inconceivable that the administration would have the courage to choose this path at present.

This stems from a deeper problem: Although we pay lip service to the equality of our dual teaching and research missions, the general sentiment among HKS administration and faculty clearly favors publishing and other methods of accumulating prestige. If faced with a choice between improving educational outcomes and accumulating fame, this school invariably chooses to allocate its finite resources the latter. Unfortunately, this pattern of placing the institution’s interests over the interests of those it serves is the opposite of what we preach.

Advertisements for faculty positions provide a glimpse at how HKS communicates its commitment to both teaching and research. Landing the job as Minos A. Zombanakis Professor of the International Financial System advertised last year on the HKS Web site required “an outstanding publication record” and “a commitment to teaching”. While both teaching and research are clearly considered, it is hard to imagine an equivalent advertisement asking for the reverse—an outstanding teaching record and a commitment to publishing. You must succeed at publishing, but in teaching, trying hard is enough.

Evaluations

Of course, there is much more to teaching than one number out of five. The same professor’s scores may fluctuate considerably, perhaps as a result of performance or students’ herd mentality. Teaching a required course will lower the average professor’s score by over 10 percent. Moreover, it is not clear that higher scores are always associated with improved learning outcomes, and students who are adverse to change sometimes punish forward-thinking professors who adopt active learning pedagogies.

The proper evaluation of an individual professor requires, at a minimum, the examination of teaching data across multiple years and courses. Teaching dossiers or portfolios, peer reviews, and assessments of learning outcomes that go beyond course content should also be employed.

Despite their weaknesses, course evaluations do provide a glimpse of the overall state of teaching at HKS, and there is clearly room to improve. Although there is no appetite to tackle this problem head-on, incremental change is possible through innovation and leadership from students, faculty and administrators alike.

Moving Forward

In some areas, modest work is already underway. Launched in 2007 and headed by an assistant academic dean, SLATE (Strengthening Learning and Teaching Excellence) is an initiative to improve teaching and learning at HKS. From planning a course, to teaching and evaluating it, SLATE provides assistance with pedagogical development to interested professors. The program has received significant support from the administration in recent years, and improving curriculum and pedagogy is one of the administration’s four long-term objectives. Since even basic budget information is kept from students, however, we do not know how well this initiative is funded.

Unfortunately, SLATE often finds itself preaching to the converted, as the professors who most invest in their teaching and learning skills are often already among the top performers.

Students are also leading change. The Student Public Service Collaborative, for example, is working to promote the benefits of experiential learning.

Further initiatives to promote a culture change in teaching and learning are also possible. Why not place a student representative on all hiring, promotion and tenure boards? Why not appoint a teaching and learning leader in each department or research center?

In the end, however, our strongest tool for change is the choices we make as students. We must do more to inform ourselves about the quality of the courses and instructors at HKS and refuse to enroll with those who consistently underperform.