By MaryRose Mazzola

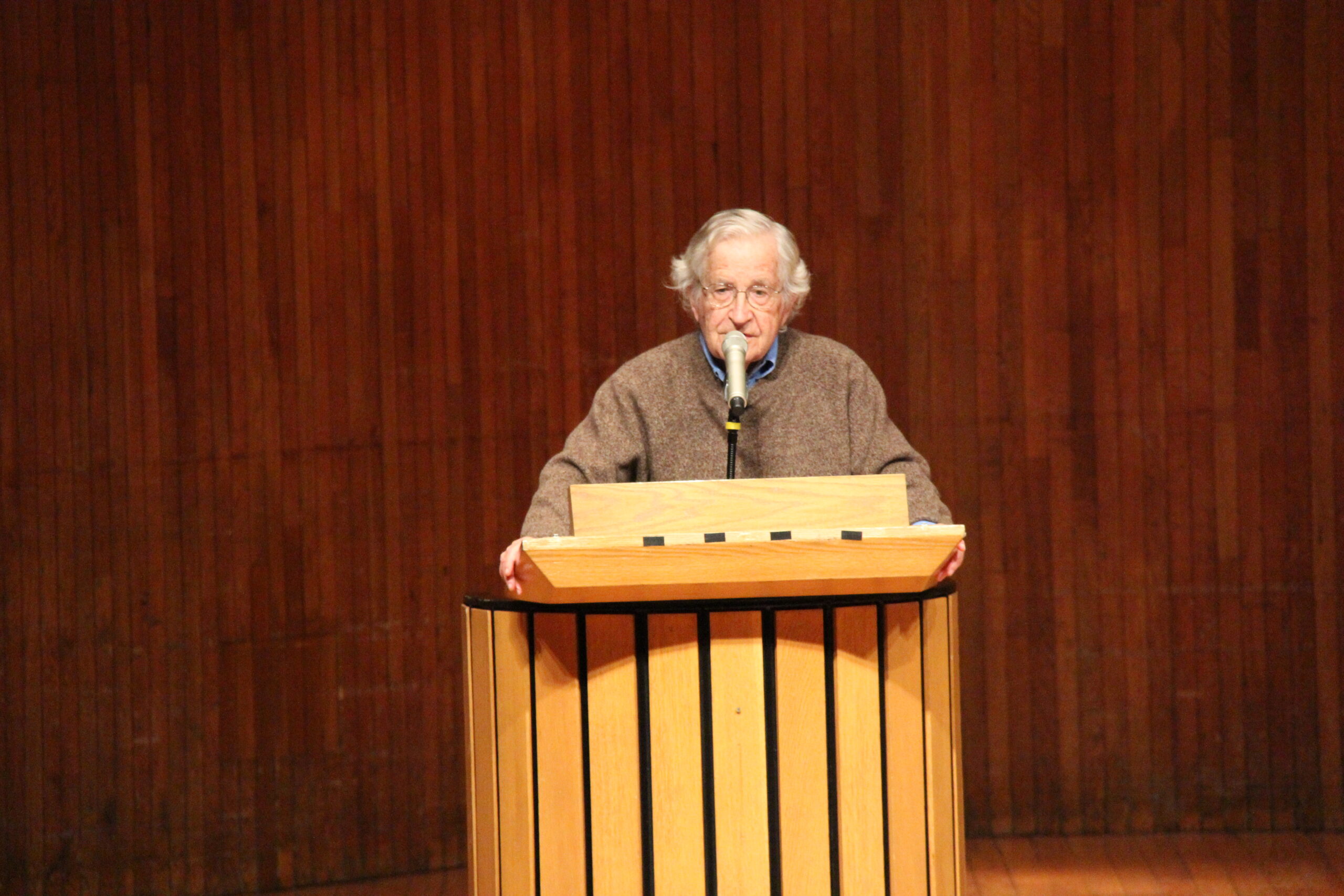

The West prefers Egypt under military rule to control by a democratically elected candidate from the Muslim Brotherhood, linguist and political scholar Noam Chomsky told a full audience at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Kresge Auditorium on October 4th.

In the discussion, which centered on the past two and a half years of political revolution and turnover in Egypt, and which was hosted by the MIT Egyptian Student Association, Chomsky noted that the 2011 uprising in Egypt was of great concern to the United States.

Yet despite the United States’ emphasis on the benefits of democracy in the Middle East, fear of democratic rule in Egypt has guided much of U.S. foreign policy in the region, Chomsky said, and this has helped to bring Egypt to its current state of rule by an interim military government.

It is far from certain that something productive will come out of the current military rule.

What was more likely, Chomsky said, is that “military will act like military acts everywhere” — by exerting its own power over the political system.

A regular commentator on U.S. foreign policy and Israeli-Palestinian relations in particular, Chomsky first taught at MIT in 1956 and has since received honorary degrees from two dozen universities around the world.

At the beginning of the Arab Spring, Chomsky said, opposition to U.S. policy in Egypt was so strong that more Egyptians were concerned about U.S.-Israel relations than about the possibility of Iran developing nuclear weapons. About 10 percent of Egyptians said that they considered Iran’s potential nuclear power to be the most imminent threat at the time, Chomsky said, whereas 80 percent cited U.S.-Israel relations to be the most formidable threat.

According to Chomsky, this concern about U.S.-Israel relations, coupled with skillful political organization by the Muslim Brotherhood, allowed the Brotherhood’s candidate, Mohammed Morsi, to win the presidential election in 2012 and thereby become Egypt’s first democratically-elected head of state. Though there were many liberal and leftist quasi-coalitions in the country that garnered more than half of the total vote, splits within organizations weakened the ability of the potential coalition to counter the Brotherhood.

However, the reign of Mohammed Morsi came to an end after protests in late June 2013, followed by a military takeover on July 3rd. Since that time, Egypt has been ruled by an interim military government.

Chomsky also highlighted some of the less-known political developments that occurred during the early stages of the Arab Spring.

For example, noting that the “uprising in part was against the imposition of the harsh neoliberal regime,” Chomsky said that independent unions organized for the first time outside of the government. He explained that these unions were responsible for adding social and economic demands to the political goals of the movement, and that their priorities mirrored those of Western labor movements and included a special focus on raising the minimum wage.

But the gains in labor rights were hardly reported in the U.S., Chomsky said.

Furthermore, he added, over the past decade, Western nations and institutions such as the World Bank have supported and praised neoliberal programs that have actually led to corruption and inequality

After 20 minutes, the discussion opened to questions from the audience.

One question came from the professor who had introduced Chomsky at the beginning of the discussion, Nazli Choucri. An MIT political science professor who directs a joint MIT-Harvard cyber international relations project, Choucri noted that Egypt has seen a gradual but persistent loss of order and subsequent erosion of the social order.

When she then asked Chomsky if there were there any conditions under which he would find it plausible or acceptable to have a military coup in Egypt, Chomsky did not seem optimistic. Citing the “ugly history” of coups in the region, Chomsky said that the military would bear a very heavy burden of proving their goals and would have to find a way to make the process temporary.

During the question and answer session, Chomsky also addressed a common theme of news coverage on the Egyptian revolution — the effects of social media — by noting that it was likely that social media had played a role in the protests, though he did not know how large a role it was.

Yet the mobilization was not completely dependent on those technologies. During a period when social media were temporarily prohibited, activism in Egypt did not stop, but instead continued in a different form, Chomsky said.

“Many uprisings have been carried out and succeeded without the Internet, before the Internet,” he noted.

But Chomsky suggested that the high amount of activism over the past few years may be starting to take its toll. A few years ago, many Egyptians first took to the streets to protest the corruption and oppression of the Mubarak era, only to return later to fight Morsi’s monopolization on politics and continued opposition.

Without an end in sight, he said, the Egyptian people are worn down by protest.