Congress is polarized. So polarized, in fact, that one would have to go all the way back to the Reconstruction era to find a similar level of discord. But perhaps more surprising is that while Congress has become more polarized, the American public has not: its dispersion of views has remained generally stable for decades. At least in terms of policy preferences, Congress is increasingly unrepresentative of most Americans.

From Congress and the White House to state legislatures and city councils, views espoused by politicians are diverging from those of the public. Pervasive gerrymandering, arcane ballot-access laws, and the influence of mass media are all in part to blame. So, too, is how we elect our officials. Voting systems – the rules that determine who wins and who loses – fundamentally impact the type of government our elections produce. These systems come in many forms, some more amenable to polarization than others.

State lawmakers are starting to reconsider them. The New Hampshire legislature is studying ranked-choice voting (RCV) this year before formally introducing HB 728, a bill that would replace plurality voting with RCV for all state and federal elections. The state’s current system of plurality voting, according to the bill’s sponsor, is exacerbating polarization. A ranked-choice alternative would “more accurately reflect the will of the people.”

Could RCV help to blunt unrepresentative polarization?

Before answering that question, let’s briefly review some mechanics. Plurality voting (also termed “first-past-the-post” or “winner-take-all”) governs most American elections, whereby a single voter chooses a single candidate, and the candidate with the most votes wins. Candidates need not secure a majority of votes, only more than any other opponent.

RCV, by contrast, requires a candidate to garner a majority. Rather than pick only a single candidate, voters rank them: their first choice, second, third, and so on. If no candidate secures more than 50% of first-rank votes in the initial tally, the candidate receiving the fewest is eliminated, and her ballots are redistributed to the remaining candidates each of her voters ranked second. This process continues until one candidate is pushed over the 50% threshold. (For more on RCV’s mechanics, see here.)

The arguments for RCV are numerous. Because RCV redistributes votes from eliminated candidates, the system protects longshot candidates from becoming “spoilers.” It obviates the need for tactical voting, whereby a voter chooses a popular-but-not-preferred candidate rather than ‘waste’ her vote on a less popular one. And emerging evidence suggests it incentivizes less negative campaigning, as candidates must broaden their appeal to gain people’s second and third-choice votes.

Its most compelling characteristic, though, is something particular to this polarized era: RCV has the potential to ensure our elected officials are more reflective of the will of most voters. The system makes it more difficult for minority voting blocs – typically the more extreme voices in the American electorate – to prevail over less cohesive majorities.

Let’s start with an illustration of plurality voting. Consider a ballot with three candidates and twelve voters. Candidate A receives five votes, or 42%; Candidate B receives four votes, or 33%; and Candidate C receives the remaining three votes, or 25%. With the most votes relative to the others – a plurality – Candidate A wins the race. Notably, Candidate A has not won with a majority of votes, only with enough of them. For a representative democracy, this raises the question: how many votes are enough? Most voters did not select Candidate A. Should this candidate represent them?

Real-world examples of this hypothetical are common. After serving two terms, Maine Governor Paul LePage left office without having ever commanded majority support, either among the general population or within his own party. In 2010, LePage secured the Republican nomination with 37.4% of the primary vote and the governorship with 37.6%. On issues such as recreational marijuana, Medicaid expansion, and LGBT rights, the Governor’s policies were often at odds with the views of most Mainers; on multiple occasions, voters were forced to override their executive through popular referendums. Polls regularly placed him among America’s least popular governors. How could an historically unpopular state executive – one who never enjoyed the support of most voters – remain in power for eight years?

A similar situation arose during the 2016 presidential primaries. Then-candidate Donald Trump failed to win an outright majority until New York’s primary, among the last ones held. He secured the Arkansas primary with 32.8% of the vote; 32.5% in South Carolina; 43.4% in Alabama; 38.8% in Georgia; 38.9% in Tennessee; and 35.9% in Kentucky. In more than half of the primaries, a majority of Republican voters did not vote for Trump. Strong factional support for one candidate defeated broadly distributed support for others. Plurality voting ignored vital information: that most Republican primary voters did not favor Trump.

LePage and Trump’s electoral successes irk a kind of basic democratic instinct: that our elected officials should represent the choices of most voters.

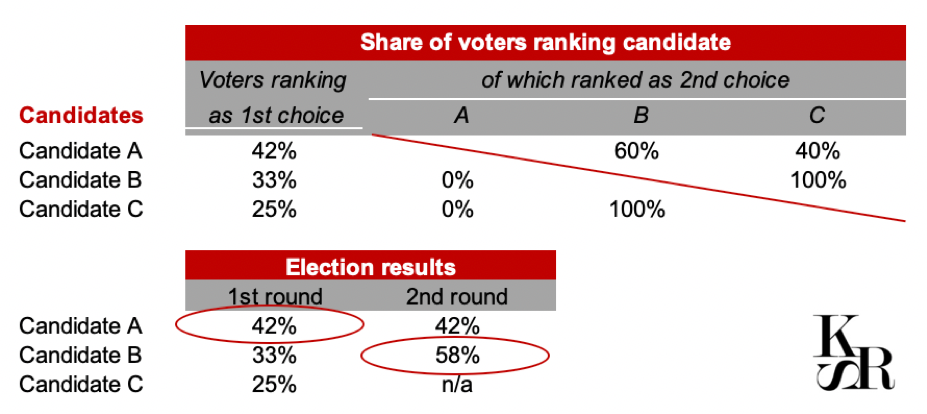

RCV expands representation through more information. To illustrate, let’s return to our stylized race, this time using RCV. Because no single candidate has secured a majority of first-choice votes, the candidate with the fewest (Candidate C) is eliminated. The three voters who ranked Candidate C as their top option, however, still have their voices heard: their second-choice option (Candidate B) acquires their votes. In the second round of tabulation, this gives Candidate B 58%. Candidate B wins. Getting as close to majority support by eliciting more complete information, such as people’s second and third choices, is the hallmark of RCV. The figure below illustrates how collecting more information from voters can eliminate a candidate without broad-based support, even if that candidate commands a plurality of votes.

While a simplified example, the basic features of this race should appear familiar. Candidate A enjoys the support of a strong minority faction: five of the twelve voters ranked Candidate A first, with their secondary support for Candidates B and C mixed. Meanwhile, supporters of both Candidate B and C universally rank Candidate A last. In other words, Candidate A might be what we typically term a polarizing candidate: one that speaks to a strong faction and is simultaneously regarded as a last-choice for a remaining majority. While Candidate B only enjoys top-place support from a third of this electorate, the 25% that preferred Candidate C would rather see B win than A: important information that would otherwise be lost. In the second round, Candidate B receives those votes, reflecting the will of a broader spectrum of voters.

Plurality voting has helped to facilitate today’s unrepresentative polarization by benefiting candidates like ‘A.’ The trend is also likely to intensify. As each party’s base continues to become more ideologically extreme, candidates like ‘A’ will reflect them. According to surveys by the Pew Research Center, the farther left or right that respondents sit on the ideological spectrum, the more likely they are to believe that “voting gives them a voice in how government runs.” With a voting system that favors these factions, the belief is well-founded.

James Madison, preoccupied with the power of political factions that might “discover their own strength,” was an early opponent of winner-take-all elections. He worried that such a system, “pregnant also with a mischievous tendency,” would reward factionalism at the expense of “the real choice of a majority.” Madison, too, feared Candidate A.

In 2018, Maine quietly made history as the nation’s first state to implement RCV for federal elections. Inspired by its success, bills like HB 728 are now surfacing in state legislatures across the country: as of this writing, in at least 14. As a voting system that favors more representative government, momentum for RCV deserves the majority’s support.

Edited by Ryan Pierannunzi

Photo by Elliott Stallion on Unsplash