This piece was published in the 28th print volume of the Asian American Policy Review.

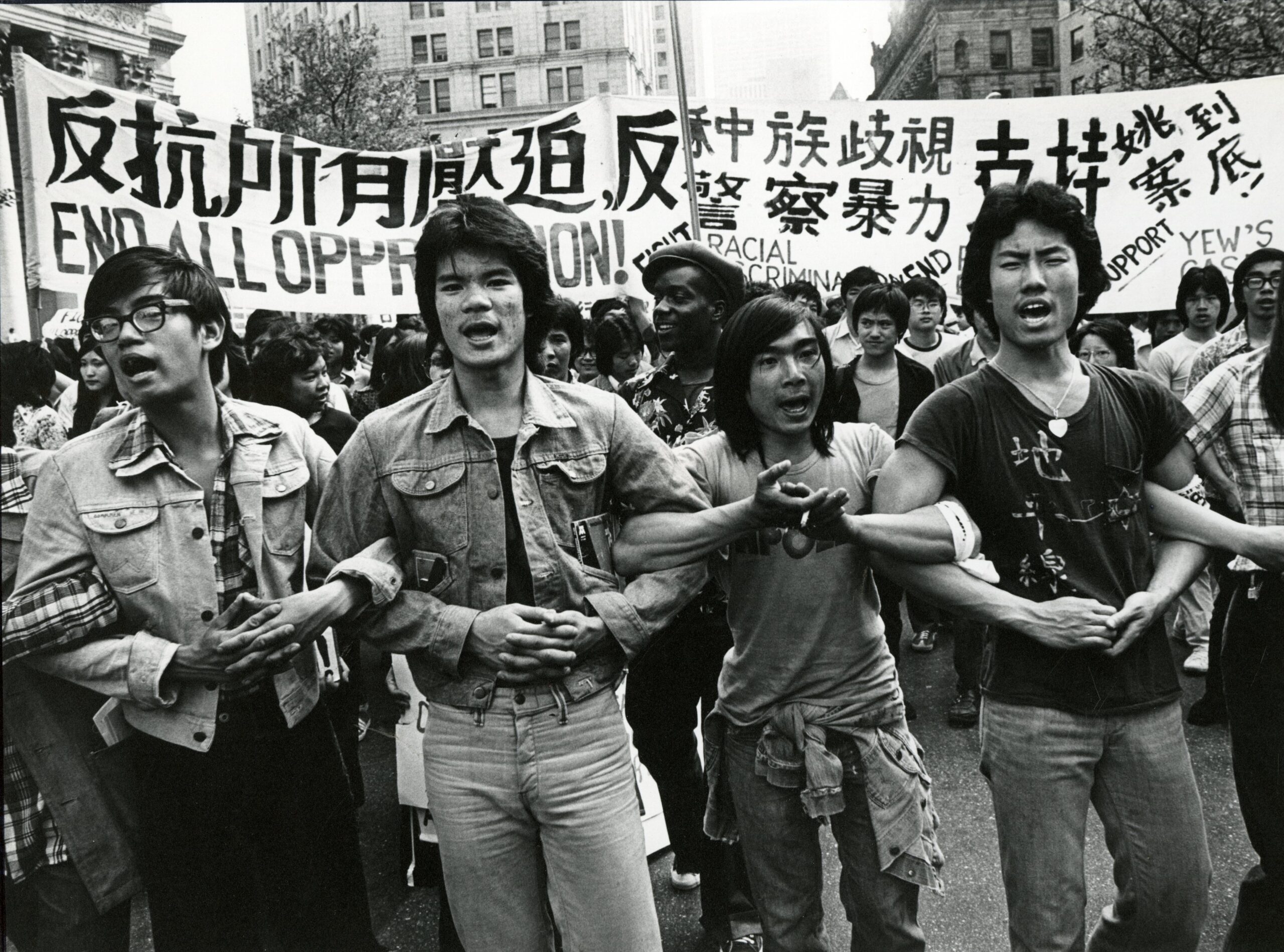

Asian American identity has historically been one of resistance, subversion, and protest. In both courts and communities, Asian Americans have fought for the right to citizenship[1], educational access[2], fair treatment[3], and working conditions[4] since the late 1800s. On U.S. plantations, Asian laborers organized across ethnic groups to strike against unfair wages and conditions.[5] During Japanese internment, the No-No Boys resisted the mandated allegiance survey.[6] In Asian enclaves across the country, groups like I Wor Kuen formed to address community needs for healthcare reform, job and draft counseling, and childcare; on college campuses, organizations like the Third World Liberation Front and the Asian American Political Alliance led student strikes to advocate for Ethnic Studies and control over hiring and retention for faculty of color.[7] In the 1960s, the Asian American Movement joined and fought alongside multiracial solidarity coalitions to protest racism and neo-imperialism in the United States.[8]

Despite this history of struggle, whiteness[9] constructed “Asian American” as a monolithic identity of submission, complicity, and model minority.[10] In response to the increased politicization of the Asian American Movement, the mainstream media created, perpetuated, and reified the model minority myth; thus, in exchange for the rich, robust history of Asian American communities and identity, whiteness reduced Asian American culture to a simple equation: a strong work ethic and family values can prevent a group from becoming a “problem minority,” regardless of historical marginalization.[11] This construction became central to the way Asian Americanness was socially understood and talked about, and in turn, a conception that Asian Americans began to internalize as our racial legacy.

As an educator and student in Social Studies Education, I do not remember reading a single K-12 Social Studies textbook where Asian American identity was discussed in detail. Had it not been for friends, mentors, and activists who advocated for the institutionalization of Ethnic Studies, I also would not have encountered this history in college or graduate school. When I work with Asian American youth, I watch them gape in disbelief when they learn simple facts about Asian American history—like that two Asian Americans ran for President in the 1960s and 70s. It is a deliberate, political maneuver that they do not know their own histories—that we have to advocate incessantly for access to this kind of education.

More commonly, I encounter Asian American students and parents who have deeply internalized the model minority myth, and who believe it better to have a “good stereotype” as a wedge minority than to occupy a “lower” position in the racial hierarchy. Where there could be an understanding of our rich history of resistance, there exists a belief in the meritocratic, individualistic, and capitalist rhetoric of bootstrapping and the American Dream. Where there could be a connection to political movements of the past and collective racial solidarity in the present, there is an aspiration to achieve, accrue, and out-do others by adhering to white cultural norms and standards. There is, presently, even an intentional effort to dismantle affirmative action for in-group gain—at the expense of historically underrepresented racial groups in higher education—using colorblind, meritocratic arguments that belittle the historical and political significance of the policy. In short, where there should be Asian Americanness, there is whiteness.

“Over fifty years after the model minority myth was first constructed, whiteness continues to reduce and erase key elements of Asian American identity from the mainstream understanding of Asian Americanness—and with it, possibilities for our future.”

Some may call this over-confidence in meritocracy, individualism, and capitalism a result of the cultural residues from the immigrant aspiration to do better by the next generation through personal sacrifice. Some of it, also, may be considered a residue of historical trauma in parents’ and students’ mother countries, where past political circumstance colors current relationships with wealth and social capital. However, these discourses ignore the responsibility of whiteness in creating these social circumstances of oppression and trauma to begin with. They turn a blind eye to American imperialism abroad and the omnipresence of capitalism as a tool of oppression and exploitation of laborers by whiteness. Furthermore, they disregard the neoimperial and corporate projects of whiteness that benefit from Asian and Asian American culture, where Asian/American subjects are often reduced to objects to be commoditized, exoticized, fetishized, and appropriated. Even where meritocratic phenomena (e.g., high-stakes testing, aspirations of going to a “good college,” and pursuing career paths for social mobility) exist in Asian countries, there is no doubt that globalization and the privileging of Westernization in developing economies have played a role in exposing these nations to whiteness. Whiteness has influenced cultural values in a neocolonial fashion.

While first, 1.5, and second generation Asian Americans try to make sense of their hyphenated and intersectional identities, they do not have access to a complex, rounded history of Asian America to see themselves situated in and to reconcile with their own stories of identity, migration, and Diaspora. Instead, they have the model minority myth. As a result, where we, as a community, could form coalitions to support one another and to protest unfair labor laws, wages, immigration policies, and racial discrimination, we work harder by the rules of whiteness to “get by.” Instead of using historical consciousness and communal strength to subvert, reclaim, and reconstruct unjust systems, we give them more power by buying in. We even compel Asian American youth to participate in whiteness by sustaining whiteness discourses of grit, obedience, and delayed gratification in regards to work and school, even where it has proven to be harmful for their mental health.[12] Over fifty years after the model minority myth was first constructed, whiteness continues to reduce and erase key elements of Asian American identity from the mainstream understanding of Asian Americanness—and with it, possibilities for our future.

Whiteness is a plague. It burrows its ideas of power, domination, superiority, and ownership into any healthy tissue it can find. It causes us to regard our fellow human subjects as competition, rather than as partners in a collective movement for liberation. It shackles us to materialism and unhealthy ideas of success that devalue physical, spiritual, and mental health, communal happiness, and interpersonal relationships. Importantly, it severs us from a rightful education of our historical situatedness and identity. As a result, we lose our sovereignty and ability to self-determine as human beings. In this political moment, more than ever, it is time to challenge and reject whiteness and the well-worn narratives it has projected on us to build community that can reclaim possibilities for Asian Americanness. On a policy level, this means pushing for the inclusion of Ethnic Studies and Asian American Studies in K-12 curricula, as well as creating community spaces and sustaining funding for cultural and political education and collective organizing. With the recent precedent set by the U.S. District Court of Arizona ruling that the Tucson Unified School District’s ban on Mexican American Studies is a violation of the 14th Amendment[13], a concerted effort to institutionalize Ethnic Studies programs has the potential to permanently establish shared historical knowledge and political language in schools. However, the mindset shift away from whiteness is a communal onus that all civic actors—beyond policymakers—must take on. It begins with changing the daily conversations we have with each other to focus on wellness, solidarity, and happiness instead of success, achievement, and competition. Continued change relies on encouraging our questioning of what is and nurturing our reimagining of what could be. Thus, as Asian Americans, we must ask ourselves: what do we owe to ourselves and others as descendants of a radical political legacy? What could “Asian American” mean and achieve as a sociopolitical entity when we demand definition and recognition on our own terms? What can we accomplish by teaching our communities about radicalness—and what could this collective conscientization do to make imagined futures realities in our communities?

References

[1] U.S. v. Wong Kim Ark (1898), Ozawa v. U.S. (1922), and U.S. v. Bhagat Singh Thind (1923)

[2] Lau v. Nichols (1974)

[3] U.S. v. Ju Toy (1905)

[4] Yick Wo v. Hopkins (1886)

[5] Jung, Moon-Kie. Reworking race: the making of Hawaii’s interracial labor movement. Columbia University Press, 2006.

[6] Murray, Alice Yang. Historical Memories of the Japanese American Internment and the Struggle for Redress. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2008.

[7] Ho, Fred. “Fists for Revolution: The Revolutionary History of I Wor Kuen/League of Revolutionary Struggle.” Ho, et al (2000): 3-13.

[8] Wei, William. The Asian American Movement. Temple University Press, 2010.

[9] Whiteness is multidimensional, systemic, and systematic. While whiteness is socially and politically constructed, it represents a position of power and structural advantage that those who benefit from whiteness hold over those who do not. For instance, white cultural practices and norms are often unnamed and unquestioned; whiteness is considered to be neutral, and because it has created most sociopolitical and historical norms, it is often talked about as if it were universal. In this specific piece, whiteness is also discussed as relational, in the sense that people of color can benefit from proximity to whiteness in a variety of social circumstances (e.g., through their class privilege or educational attainment). For more, see Fyre (1983), Kivel (1996), hooks (1994), Frankenberg (1993), and Henry & Tator (2006).

[10] Kwon, Hyeyoung, and Wayne Au. “Model minority myth.” Encyclopedia of Asian American issues today. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO LLC (2010): 221-30.

[11] Petersen, William. “Success Story, Japanese-American Style.” New York Times, January 9, 1966.

[12] Lee, Sunmin, Hee-Soon Juon, Genevieve Martinez, Chiehwen E. Hsu, E. Stephanie Robinson, Julie Bawa, and Grace X. Ma. “Model minority at risk: Expressed needs of mental health by Asian American young adults.” Journal of community health34, no. 2 (2009): 144-152.

[13] González v. Douglas (United States District Court, District of Arizona, Final Ruling Document 487, December 27, 2017).