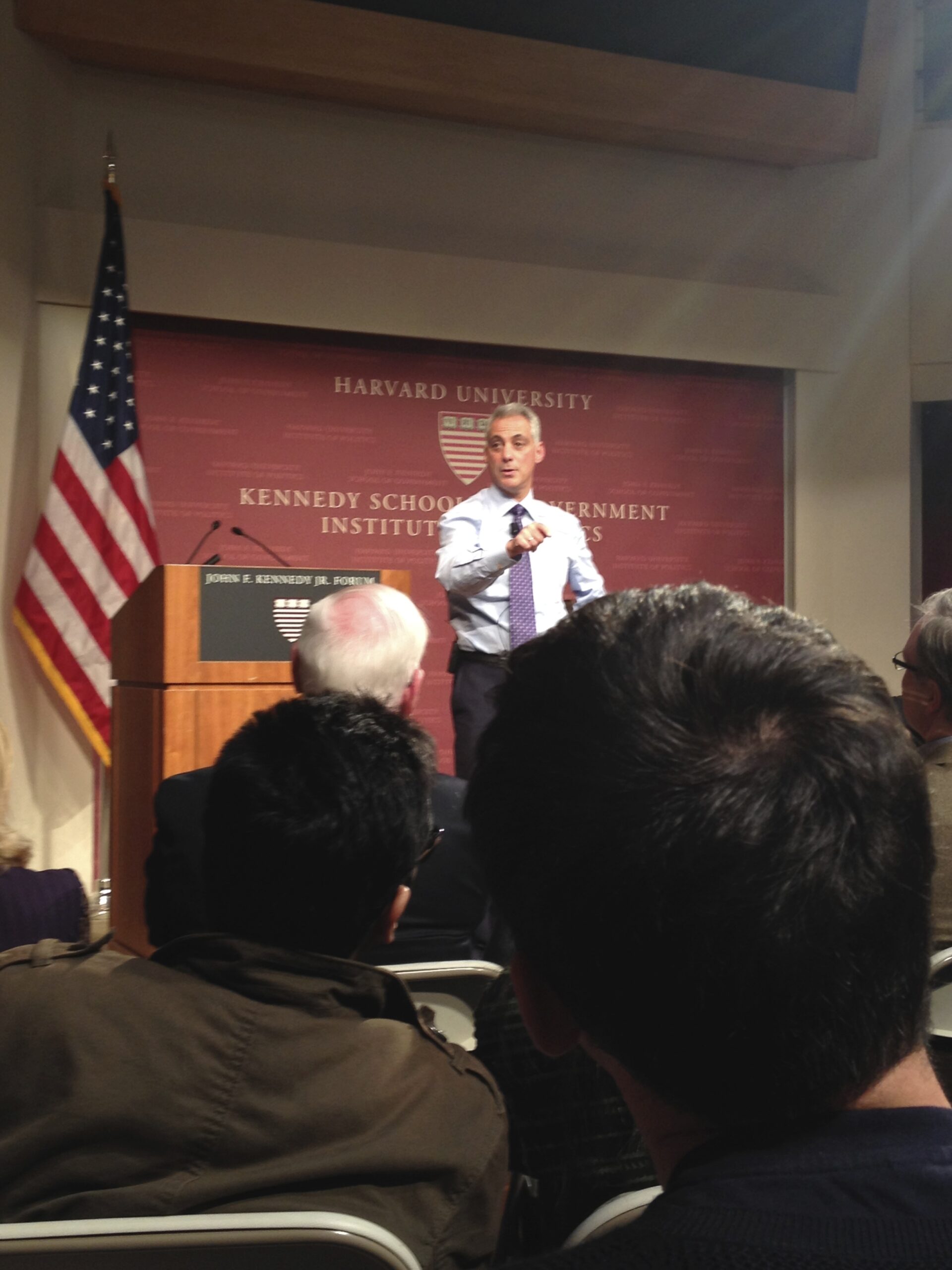

Addressing a packed John F. Kennedy, Jr. Forum on Friday, October 18th, former Congressman and White House Chief of Staff Rahm Emanuel said the single greatest job he has ever had is his current one: the Mayor of Chicago.

“Cities are not only where things happen but where things get done,” he said, noting that in no other position could he move the needle for the city like he can now.

However, running America’s third largest city has required Emanuel to learn on the job. He explained that there was no manual for the position as mayor, but that improving education and infrastructure have been major priorities for his administration since taking office in 2011.

As mayor, Emanuel has had to tackle a variety of challenges.

One example is Chicago’s relatively high and widely publicized crime rates. When discussion moderator and Politico senior political reporter Lois Romano broached the topic, Emanuel conceded that Chicago’s crime rates were higher than those of some other cities. However, he said, overall crime has fallen over the past two years, and homicides have decreased by about 20 percent.

Moreover, Emanuel said, Chicago takes more guns off the street each week than do New York City or Los Angeles. Noting that Chicago’s current minimum sentence for gun felonies is a year — the same sentence given to shoplifters — Emanuel said that he is currently pushing for a three-year minimum for gun felonies, similar to a policy currently in practice in New York.

Education, however, dominated the discussion, with the mayor emphasizing his goal for the city’s students “to be 100% college ready and bound, or career ready.”

His annual budget, to be released in late October, includes increased investment in children for the third year in a row. Since he took office, Emmanuel said, total school funding has increased by 10 percent, even in the face of budget constraints.

For Emanuel, students can benefit from investment in education starting at a young age. One of his favorite educational investments, he said, is the renovating all of the city’s playgrounds.

“Every child, regardless of where they live, what their income is or what their race is, will live within a ten-minute walk of a park in Chicago,” he explained.

Improving Chicago’s seven community colleges represents another one of the administration’s top priorities.

Turning to the crowd of Harvard College and Kennedy School students, Emanuel noted, “When you go somewhere and say, ‘I went to Harvard,’ it has economic value.”

“I want it to be the same if Chicago students go somewhere and say, ‘I went to Malcolm X [College],’” he said. “That should have economic value too.”

But not all of Emanuel’s education initiatives have enjoyed widespread popular support.

For example, one audience member pointed out that the teachers union has promised to make Emanuel a one-term mayor because of the 50 schools he has closed across the district.

The mayor conceded that “the political system might be embattled,” but argued that “the kids are better off.”

“For two years running, math and reading scores went up,” he said. “We now have more Level 1 schools [which are awarded “Excellent Standing”] than ever before.”

At the same time he was eager to talk about his own administration’s efforts to improve education, he also was critical of the federal government.

Apartment from HeadStart and the Clinton administration’s welfare reform, Emanuel said, “You can’t tell me a single thing that the federal government has done for kids in the last 50 years.”

Asked by Romano if he had a better appreciation for the effect of budget cuts now that he was on the other side, Emanuel responded simply, “Yes.”

Emanuel’s remarks resonated with some audience members who had previously had careers in education. Audience member Billy Powers, a first-year master of public policy student and former pre-school teacher in Chicago’s South Side, said that he was heartened by the mayor’s focus on education.

“It’s really encouraging to hear how committed he is to early childhood education, particularly given the vast set of short and long-term challenges Chicago is facing,” Powers said.

Emanuel ended the discussion by stressing the shared responsibility of school improvement. While many conversations about education focus on the role of teachers, principals need to be evaluated, too.

“Who runs that building? Who creates the culture of that school? Who sets the goals? It’s not just teachers,” Emanuel said.

He cited his administration’s efforts to involve parents in their children’s education.

“If you have an involved parent, a motivating teacher and an accountable principal, I don’t care where you come from, you’re going to succeed,” he said.

But for Emanuel, it is not only parents, teachers and principals who are responsible for students’ education.

“If you’re an adult, you’re accountable for children. That’s the way I see it.”