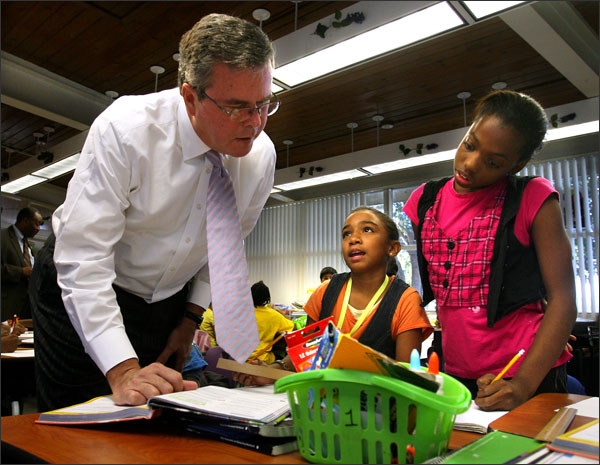

Photo credit: Joe Burbank/Orlando Sentinel/AP

BY GOVERNOR JEB BUSH

As adults, we are responsible for the educational success of our children. And as adults we can easily thwart young learners.

Let me ask you a question. A child enters kindergarten. His mother is a single-parent who works a minimum wage job. Perhaps he lives in the inner city or he is an immigrant learning English. What do we expect of him?

Do we expect him to read by the third grade, learn fractions or write coherent sentences? Do we expect him to graduate from high school equipped to attend college, begin a career or join the Armed Forces?

Or do we look at his circumstances, dumb-down his expectations, and give his school excuses not to make every effort to ensure he learns. Do we just shuffle him through the system? Promote him out of third grade even if he can’t read. Let the fourth grade teacher deal with it, who will let the fifth grade teacher deal with it until he is so far behind nobody can deal with it.

Sadly this isn’t just a hypothetical question, but it is reality for countless students across our nation. Their dreams and potential are being crushed under system that neglects its true purpose.

When you boil down education reform to one guiding principle, it is this – every child can learn.

And so, we must refuse to accept excuses that only set children up for failure and deny them the opportunity to achieve the American Dream. That is immoral on an individual level and unsustainable on a national level if we plan to be world leaders in the 21st century. We must set high expectations for every child and put in place the strategies to achieve them.

Many important figures in education have contributed tremendously to education, inspiring the rest of us. Iranetta Wright, a principal in Jacksonville, was assigned to the worst performing high school in Florida. She transformed a perennial F school to a B school, and she now helps other principals improve their schools. Wright advises these principals, “You have to be relentless about it, and it’s not for the faint of heart.” We must heed her words and champion our students.

Public education has become a labyrinth of political, bureaucratic and union empires that depend on a captive population of students and minimal quality control. In education, there is a resistance to change and a desire to maintain the status quo, with many groups fighting back against reform. Despite these efforts, education reform is maturing into a broad-based, bi-partisan movement to combat decades of failure and fiscal recklessness by an education system dominated by union politics and enabled by pass-the-buck politicians.

For decades, our most vulnerable kids have fallen through the cracks and under the radar. Half of our Hispanic and African American fourth graders are functionally illiterate; they are two and a half years behind white students. This year, only 25% of students taking the ACT qualified as college-ready on all four sections. How will America remain the most dominant nation on earth when we are a middling nation in the classroom?

If trying to reverse this is a war on public education, we need to revisit the definition of public education. My suggestion is this: It is the public’s obligation to provide each child with the best education possible without regard to provider.

As parents, teachers, employers and leaders, our society has a responsibility to provide students with an education that prepares and inspires every child to achieve his or her God-given potential.

To accomplish this, we must rely on a variety of reforms, starting with early literacy. Illiteracy destroys lives. Students who can’t read are four times more likely to drop out. Eighty-five percent of kids who enter the juvenile-justice system are functionally illiterate, and 70% of prison inmates cannot read above the fourth-grade level. Literacy is the ground upon which students gain knowledge and build their skills, and we need to make sure each child has that foundation before they are promoted to fourth grade.

Next, we need school choice. With the most diverse student population in history, it defies common sense to corral them all in the same early 20th-century education model and expect them to thrive. Bureaucracies are not designed to innovate or compete, and they don’t like accountability. Consequently, we have an education system isolated from the very forces that drive American innovation and success. We need more options – charter schools, home schools, vouchers, tax-credit scholarships, and Education Savings Accounts – so parents can shop for a school that best fulfills their children’s needs.

Third, we need to make education relevant to 21st century kids. Today’s kids are digital natives, and with digital education, they can go to class anytime, anywhere, in their own style and at their own pace. Digital learning is an education equalizer. It enables kids in rural Mississippi to take the same Advanced Placement courses available to students in Boston, and allows a math whiz to complete Algebra 2 in six months while other kids might need 11 months. Yet, in most states, protectionist laws hinder the advancement of digital learning because it threatens union jobs. We cannot let our past thwart the future and put students at a disadvantage.

Another vital area of reform is accountability. The old model of education that made student achievement optional had predictable results: kids who learned easily got the best education and kids who struggled got the worst education. We can stop this by demanding all kids be taught and sanctioning failure and rewarding success when we measure results.

The best accountability system I know of is a simple A-F grading scale based on student learning. Transparency should be encouraged, not feared, and this system gives parents and the public an easy-to-understand snapshot of the state of education at their child’s school. The best part is, this grading system works. For example, in 2005 Florida began including the progress of students with disabilities in our grades. Since then Florida has led the nation in learning gains by students with disabilities, according to the Nation’s Report Card.

Next, we must upgrade the teaching profession because great teachers matter a lot. A child in the classroom of a great teacher gets a year and a half of learning in a years’ time while a student in the classroom of an ineffective teacher only gets half a year worth of learning. So when school lets out in June, the student who had a great teacher walks out the door a full year ahead of the student who had an ineffective teacher.

Yet we pay both teachers the same, seniority – not effectiveness – would determine a layoff decision, and if the great teacher got frustrated and quit, little if any effort would be made to keep her. While the current model based on tenure and seniority may be a union-friendly model, it is certainly not a child-friendly model and it fails to attract the best and brightest into the teaching profession. Great teachers must be recognized and rewarded. That will happen if we eliminate tenure and evaluate and pay teachers based on their performance instead of how long they’ve been on the job or how many degrees they’ve accrued.

Finally, high standards are the most basic element of reform. Standards define what children are expected to learn over their school year and what they will need to know to succeed in each grade. Ultimately, the quality of the standards determines whether a high school diploma is worth more than the paper it is printed on.

To compete with the rest of the world in the 21st century, we must produce competitive high school graduates ready for college or meaningful careers. That means we have to raise the bar to make sure the skills they are learning are aligned with what employers and college presidents expect high school graduates to know. These skills include critical thinking, problem solving and verifying work. The Common Core State Standards were designed based on these skills.

I understand there are those opposed to the standards. But we need to hear more than just opposition. We need their solutions for the hodgepodge of dumbed-down state standards that have created group mediocrity in our schools.

Criticisms and conspiracy theories are easy attention grabbers, and solutions are hard work. We need problem solvers willing to be decisive and resolute. Delay is a strategy designed for the comfort of adults, not the progress of children.

In 1984, the Florida education commissioner complained that the pace of reform was overwhelming and that Florida need “some more time to chew what we already have bitten off.’’ When I became governor 14 years later, Florida was still was chewing, and our kids were at the bottom of the barrel in national academic rankings.

We abandoned delay and started moving full steam ahead. This strategy made many adults very uncomfortable, but in a few short years, Florida became a national leader in advancing the academic achievement of its children. We discovered kids have a remarkable ability to meet expectations; we just have to get adults on the same page.

There was a beloved pediatric surgeon in Orlando named Dr. Ronald David. Diagnosed with terminal cancer, he spent his last years in the operating room, restoring the most fragile of lives. When asked why he was so passionate about his job, he had this simple response, “I like the duration of the cure.’’

Saving a young life produces the potential of a lifetime of purpose and meaning. We need to think of education in those same terms.

A quality education helps cure poverty, drug abuse, crime and imprisonment. While education reform is tough, taxing and politically risky, it is absolutely necessary because it shapes the futures of millions of children. Ultimately, the effect of the cure is wonderful when we succeed; and the extent of the consequences is frightening when we fail.

Meaningful futures hang in the balance for millions of children. So let’s commit to making changes that better serve our children, the leaders and innovators of tomorrow.

Jeb Bush served as the 43rd Governor of Florida from 1999-2007. He is the second son of former President George H. W. Bush and the younger brother of former President George W. Bush. Originally shared at the Foundation for Excellence in Education’s 2013 National Summit on Education in Boston on October 17, 2013. This piece is also featured by the Harvard Economics Review here.

Photo source here.