BY JOSÉ LUIS GALLEGOS

Throughout the 2018 presidential campaign, 60% of Mexicans believed that Andres Manuel López Obrador, the face of the left-wing opposition, was a populist. Since he was first elected mayor of Mexico City two decades ago, his opponents relentlessly portrayed him as a “danger to Mexico” and compared him to Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez, as well as US President Donald Trump. However, Obrador used the populist label to his advantage on the campaign trail, declaring to the media and to voters, “If supporting the poor means to be a populist, write me down on that list.” He was elected in a landslide victory. Next month Obrador will take office, and he has already revealed that he will be as populist as president as he was as a candidate.

Populism is a rhetorical style that encompasses two salient elements. The first is the claim that the only legitimate authority flows directly from the people. The second is an attack on elites for being morally corrupt and betraying the public trust. This rhetoric, however, is neither specific to Latin American politics nor exclusive of left-wing candidates. A study from the US revealed that challengers, regardless of their ideology, tend to use populistic expressions during campaigns more frequently than incumbents do. However, politicians often become less populist once they assume office. In a multi-party electoral system, like in Mexico, one might expect all challenging candidates then to employ populist rhetoric to a similar degree but to differentiate themselves from one another using ideology and policy positions along the campaign trail.

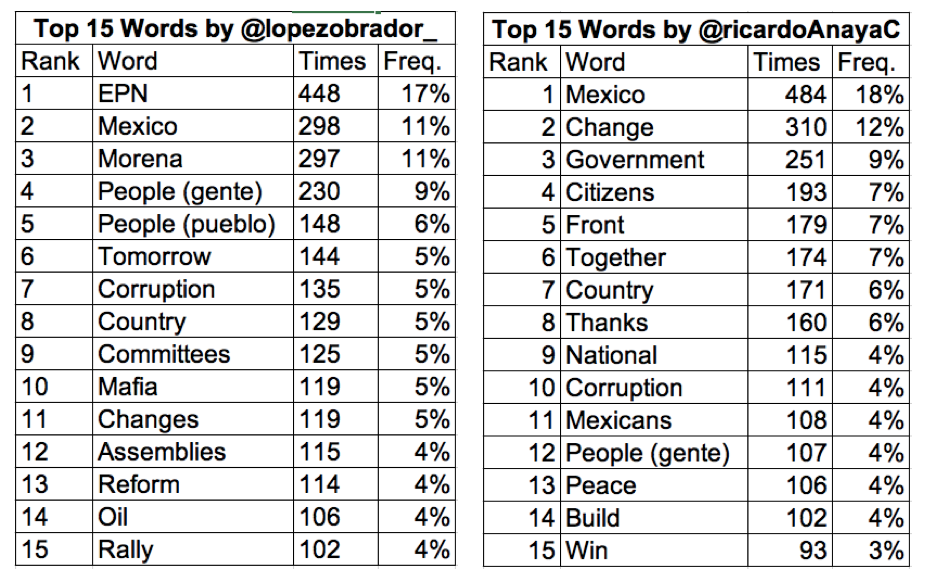

Nevertheless, this was not the case for the 2018 presidential election, as other presidential candidates did not use populistic expressions nearly as often as Obrador. To illustrate this point, I analyzed the Twitter accounts of Obrador and the presidential runner-up, Ricardo Anaya, leading up to the election.[1] The results revealed Obrador’s language on the social media platform to be considerably more populist than Anaya’s.

For example, Obrador repeatedly used two collective nouns to refer to the public: gente and pueblo. Both translate to “people,” but the second term, pueblo, evokes the idea of a unified community with shared interests – a salient characteristic of populist discourse. Although Anaya also employed the term gente, he does it half as frequently as Obrador. Anaya also favored collective terms like “citizens” and “Mexicans,” which have a more pluralistic connotation.

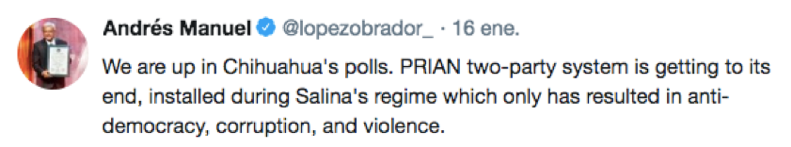

Moreover, the attack against elites was evident in Obrador’s frequent use of the words “mafia” and “corruption.” Obrador’s antagonism against ruling parties not only served to differentiate himself from those in power, but it also encouraged Mexicans of a lower socioeconomic status to differentiate themselves from the current government. It is no surprise that in his very first presidential debate in 2018, Obrador’s most repeated word was pobres – the poor. The rhetoric of social class cleavage was particularly useful for “stealing” votes from the incumbent party, which has historically received the support of Mexico’s rural and marginalized populations.

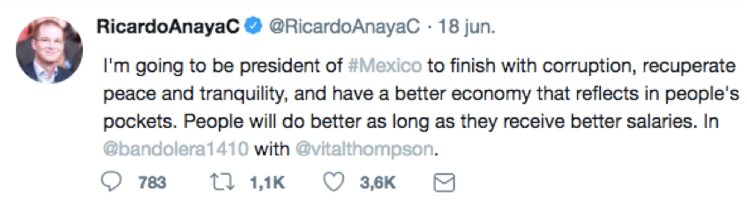

While the denunciation of “corruption” is not necessarily a populist stance, as government corruption was one of the most important topics on the public agenda in Mexico this past year, there was a crucial difference in the use of the word by each candidate. Obrador tended to depict corruption as an inherent attribute of the governing elite and specifically targeted his criticism toward the outgoing president, Enrique Peña Nieto, to whom he refers using the initials “EPN.” In contrast, Anaya refers to corruption in more general terms without mentioning President Peña Nieto, addressing it as a public policy issue as opposed to an attack on political opponents.

In analyzing the discourses of these two candidates on Twitter, it is clear that Obrador did not simply use populist language because he was a presidential challenger; when compared with Anaya, Obrador’s populism appears to be a consistent personality trait. However, if Obrador was a populist candidate, does that mean he will also become an authoritarian president?

His campaign communication, even on Twitter, did not offer sufficient evidence to indicate authoritarianism. Further, Mexican political analyst, Carlos Bravo, argued that when Obrador was Mexico City’s mayor, he did not show authoritarian tendencies. On the contrary, he exhibited a strong sense of pragmatism that prevented him from any radical ideological polarization.

What is different, however, is that Obrador’s political coalition won a stunning majority of seats in Congress. The concentrated support for Obrador will test the system of checks and balances in Mexican democracy. Yet, the best constraint to an expansive power is not the institutional design of the political system itself, but the active role of civil society in monitoring government and making it accountable to the people. Though it is very likely that Obrador will be as populist in office as he was on the campaign trail, the capacity of Mexican citizens to keep the new government in check will be the best protection against any authoritarianism.

José Luis Gallegos is a Master in Public Administration candidate at the Harvard Kennedy School of Government. He earned a Bachelor of Arts in Political Science at the National and Autonomous University of Mexico and previously worked as a legislative advisor in the Mexican Congress. Follow him on Twitter at @jlgallegosq

[1] The data presented were generated using the Twitter analytics application, “Burrrd”. The “freq. rate” was calculated by totaling the number of times a word was used in the period between August 2017 and August 2018 and dividing by the number of the top words generated (15 in this case).

[2] The original tweets from @RicardoAnayaC and @lopezobrador were tweeted in Spanish. They were translated to English by the author.

Edited by Katie Miller

Photo credit: Presidencia de la República Mexicana