BY DANIEL TOSTADO

Among all the numerous Latin phrases that I have picked up at law school, today this one is most apt: “De mortuis nihil nisi bonum,” –Do not speak ill of the dead.

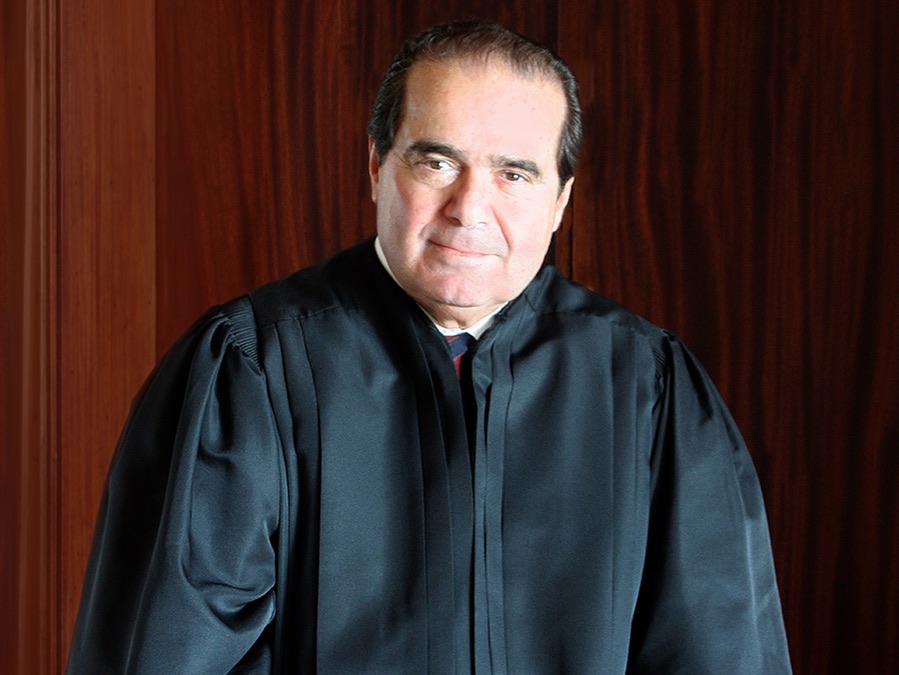

A war of words started innocuously enough on Sunday, when Georgetown Law Dean William Treanor issued a statement on behalf of the Georgetown Law community mourning the loss of “a giant in the history of law,” Justice Antonin Scalia.

Yet on Tuesday, in what may only be considered a dissenting opinion to Treanor’s statement, Professors Louis Seidman and Gary Peller denounced Treanor’s sentiments in an email to the whole student body, replying, “I imagine many other faculty, students and staff, particularly people of color, women and sexual minorities, cringed at the headline and at the unmitigated praise with which the press release described a jurist that many of us believe was a defender of privilege, oppression and bigotry, one whose intellectual positions were not brilliant but simplistic and formalistic.”

Grab your popcorn.

On Wednesday, Dean Treanor essentially doubled down, noting Scalia’s habit of generously sharing his time with law students, and he reaffirmed it was a time for mourning. (Scalia did make frequent appearances—in my 1L year, I saw him several times and spoke with him once.) Later on Wednesday, Professor Randy Barnett also sent a long and vociferous email to the entire student body, defending Scalia and decrying Peller’s message as “callous.”

In Professor Peller’s viewpoint, the extent to which a Justice should be mourned is proportional to the extent which that Justice promoted, or did not, the civil rights of vulnerable groups. The strong example is Scalia’s scathing dissent in Lawrence v. Texas. Denigrating homosexual intimacy as “sodomy” 37 times in the opinion, Scalia asserts the right of the state of Texas to criminalize homosexual intercourse if it so chooses. Until the end of his career, Scalia maintained his prerogative to view homosexuality as sinful, and to let that guide his judicial opinions. Justice Scalia’s time on the bench, more than any other recent Justice, stirred controversy.

But Justice Scalia is largely responsible for popularizing and mainstreaming an entire legal doctrine, Originalism. The doctrine asserts that the words in any legal text should be judged according to what the words meant at the time the text was published. Though the belief that the Constitution was “living, breathing document” was in vogue in the 1980s when Justice Scalia was named to the Court, the zeitgeist had shifted towards Originalism by the end of his tenure.

In 2014, for the first time on any law school campus, Professors Larry Solum and Randy Barnett taught a class exclusively about the legal doctrine Originalism. As liberal and conservative Originalists, respectively, these professors emphasized that Originalism is the closest approach to an objective interpretation of the meaning of any historical legal text.

A great example is the Second Amendment. Its text reads, “A well regulated Militia being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms shall not be infringed.” What did the framers mean by “Militia,” or “keep and bear,” or “arms?” An Originalist jurist could have a field day analyzing researching this question. And it was largely on Originalist grounds that the 2008 Supreme Court gun control case District of Columbia v. Heller was decided.

In spite of its now widespread popularity, Originalism is still not properly understood by the media at large. In his paean to Justice Scalia, George F. Will wrote in the Washington Post on Monday, describing how a justice construes, “the text of the Constitution or of statutes by discerning and accepting the original meaning the words had to those who ratified or wrote them.” [Emphasis added.] That approach is called Private Intention Originalism, and it is not what Scalia endorsed. The Constitution had many framers over several years, so whose intentions count? Additionally, framers’ intentions are subjective, and the meaning of words may be different to the legislator than to the public at large. Justice Scalia instead promulgated Original Public Meaning Originalism, where the words mean what they meant to the public, including judges, at the time of the publication.

The strength of Originalism lies in its purported objectivity to restrain judges from diverse interpretations. The original meaning serves as a lodestar upon which the jurist can base his or her opinions. Alternative approaches on the Supreme Court, such as “Purposivism” (analyzing a statute based on the purpose it meant to serve) or “Living Constitutionalism” (the meaning of the words in the Constitution changes over time), have declined in stature due to Originalism’s emergence.

From a policy perspective, the implications are enormous. In D.C. v. Heller, for example, all nine Justices grounded their opinions in Originalist justifications. The decision, based on a close reading of the “well regulated Militia” language, decided that gun-owners had not only a collective right to bear arms, but an individual right as well. Policy-makers as well have started embracing Originalism— recently the Republican House Majority opened session by requiring that every bill be linked to constitutional provision.

In a twist of events that Scalia would surely appreciate, now the conversation has turned to the question of whether Originalism requires a President should nominate a Justice in an election year. A Slate article on Tuesday points out that there is “no reason for an Originalist to oppose an Obama nomination on constitutional grounds,” given that the Constitution gives no limit to when a President may nominate to Court.

That is the legacy of Justice Scalia. He has left an indelible mark on our nation’s jurisprudence. I believe in time, he will be considered the most influential American Jurist since Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes. But we need not wait for the future to determine how impactful he is—there is already an entire generation of law students who have been challenged, cajoled, and entertained by a man who decried the, “legal argle-bargle” and “jiggery-pokery” in his opinions. We may choose to mourn the man, or not, but we will never forget his impact.

Daniel Tostado is second-year Master in Public Policy student at the Kennedy School and a third-year law student at Georgetown University Law Center.

Photo via Wikimedia Commons