BY JASON HUNG

In 2001, Lord Jeffrey William Rooker, then UK Minister of State for Asylum and Immigration, asked Prime Minister Tony Blair whether there was a legal way an asylum seeker could enter the United Kingdom.[1] The latter bluntly denied such a possibility. After current PM Theresa May took over the office, she argued that the UK must fulfill its moral duty to help individuals in desperate need.[2] At the same time, May reiterated the importance of restricting the living standards of those lodging an asylum application within the country as a means to restrictively control the intake of asylum seekers.

While the right to seek asylum is enshrined in the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, states, including the UK, are not necessarily obliged to host asylum seekers.[3] Even when they choose to do so, states retain the authority to limit the comfort of asylum seekers in order to ensure their border integrity and exclude unfavorable asylum seekers.[4] [5] [6] However, as stated in Article 31 of the 1951 Refugee Convention (which the UK has ratified), states are barred from imposing penalties on those seeking asylum if life or freedom is at stake.[7] According to these obligations under international law, it is clear that current UK asylum policies are too restrictive at three stages: when (1) asylum seekers reach the border; (2) their asylum requests are denied; and (3) their asylum requests are pending.

(1) Eligibility to apply for asylum

The political rhetoric surrounding asylum in the UK emphasizes regulatory efforts to ensure border integrity, applying a “state of exception” to asylum seekers who come from a list of purportedly safe third country (STC) and safe country of origin (SCO).[8] STC and SCO refer to the presumption that asylum applicants’ life and liberty will not be threatened in the country from which they entered the UK and in their country of origin, respectively.[9] [10] All asylum seekers arriving from a list of presumably safe countries, including Germany, Switzerland, and the United States, should be primarily protected by these “safe” countries.

Currently, the UK is overusing the STC and SCO policies relative to its European Union neighbors. According to the European Commission, the UK considers 27 countries to be SCO — more than any other EU Member State.[11] In doing so, the UK fails to fulfill its moral and legal responsibilities to accept individuals with well-founded threats of violence and freedom. For example, among EU Member States, only the UK and Slovakia consider Kenya a safe country — despite the threat posed by al-Shabab terrorist groups.[12] The UK should urgently eliminate potentially unsafe countries on its STC and SCO lists. Furthermore, each asylum application should be assessed on an individual basis, and asylum seekers coming from countries listed as STC and SCO but encountering threats of life and freedom should enjoy the right to asylum in the UK under the discretion of the Home Office.[13]

(2) Ineligibility to apply for asylum and immigration detention

While asylum seekers coming from non-STC and non-SCO countries can apply for asylum in the UK, those whose applications are unsuccessful are consequently removed from the country.[14] Asylum seekers who are pending removal or are reluctant to be removed voluntarily are detained, in most circumstances, at one of the 11 immigration removal centers (IRCs).[15] [16] The major concern here is that detained asylum seekers in the UK face unspecified limits on the length of detention.[17] In fact, the UK is the only country in the EU with no detention time limit in IRCs.[18]

In principle, immigration detention should always be non-punitive and subject to “necessity.”[19] However, since the UK did not sign the European Union’s Return Directive, asylum seekers could theoretically be detained excessively and indefinitely, without “necessity.”[20] Izabella Majcher, a researcher at the Global Detention Project, dubs such an indefinite detention system “crimmigration,” drawing a link between asylum seekers and presumed criminality.[21] Although the UK is not legally obligated to follow other European countries in establishing a detention time limit for immigration detainees, this “crimmigration” system suggests that immigration detention in the UK violates both the non-punitive and necessary principles.

(3) Pending asylum application and destitution

Those who successfully pass the screening of asylum applications are given limited financial and material assistance to live in the UK while their asylum requests are pending. Under Section 95 of the Immigration and Asylum Act of 1999, asylum seekers are entitled to £5.28 (approximately €5.94) per day[22] and are only eligible to work after waiting for a decision for up to 12 months.[23] In neighboring countries, asylum seekers often enjoy more benefits for subsistence and are allowed to work after a shorter waiting period. In Germany, asylum seekers who are financially responsible for their own accommodation are entitled to a monthly allowance of €50.1 per day,[24] as well as “other benefits” such as financial assistance in case of illness and pregnancy. Moreover, they are eligible to work after waiting for an asylum decision from three to six months.[25]

Since government support is insufficient and most asylum seekers in the UK are prohibited from work, destitute asylum seekers have no choice but to work illegally to support themselves.[26] If arrested, these asylum seekers will be detained in detention centers, which could entail stressful and inhumane living conditions.[27] As such, the UK should lodge judicial reviews to ameliorate the entitlement of financial and material assistance to those applying for asylum, in addition to shortening the necessary wait time to be eligible to work.

The big picture

Asylum policies in the UK are highly restrictive. Compared to other European countries, UK asylum policies disproportionately favor immigration control over humanitarian responsibilities under international law. These restrictive policies often alienate asylum seekers within the country, rendering those seeking asylum to live in an inhumane and unsafe environment. By pursuing the policy reforms proposed here, the UK can ensure that those under persecution are able to seek asylum within the country, in addition to maintaining the fundamental dignity of every human being and conforming to European standards for the treatment of asylum seekers.

Edited by Nikhil Kumar

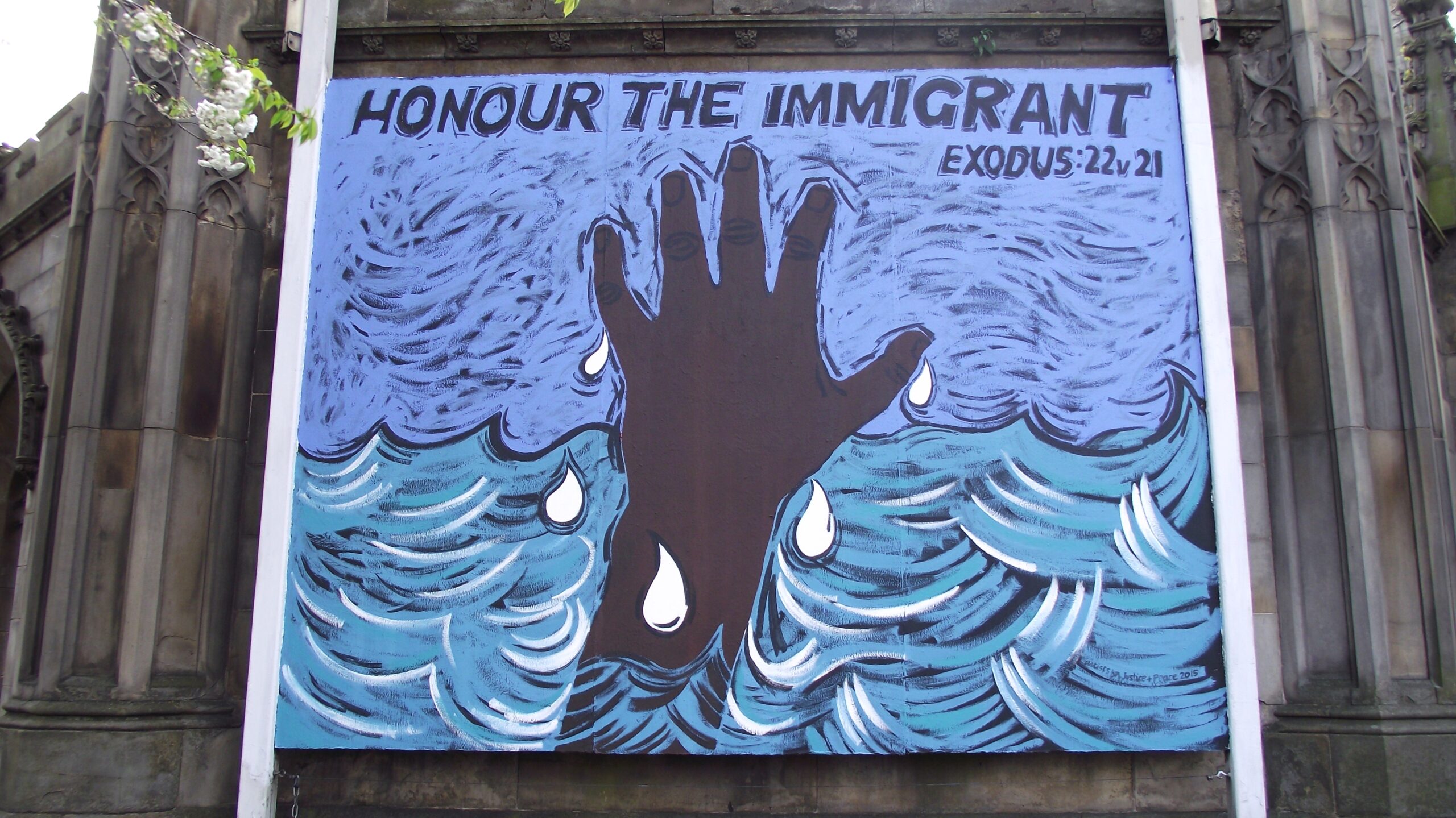

Photo: Mural at St. John’s Church on Princes Street in Edinburgh // Credit byronv2 on Flickr

[1] Gibney, Matthew. The Ethics and Politics of Asylum. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

[2] CCHQ Press, “Theresa May Speech: A Beacon of Hope,” accessed October 5, 2015, http://press.conservatives.com/post/130940020830/theresa-may-speech-a-beacon-of-hope.

[3] Benhabib, Seyla. ““The right to have rights”: Hannah Arendt on the contradictions of the nation-state”. The Rights of Others: Aliens, Residents, and Citizens. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Jonathan Darling, “Domopolitics, Governmentality and the Regulation of Asylum Accommodation,” Political Geography 30, no. 5 (2011): 263-71.

[6] Gundogdu, Ayten. Rightlessness in an Age of Rights. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015.

[7] Squire, Vicki. The Exclusionary Politics of Asylum. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009.

[8] Sharon Pickering. “Border Terror: Policing, Forced Migration and Terrorism,” Global Change, Peace & Security 16, no. 3 (2004): 211-26.

[9] Refugee Council, “Safe Third Country – United Kingdom”, accessed March 31, 2018, www.asylumineurope.org/reports/country/united-kingdom/asylum-procedure/safe-country-concepts/safe-third-country.

[10] European Commission, “Safe Country of Origin”, Last updated February 13, 2019, https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/content/safe-country-origin_en.

[11] European Commission, “An EU “Safe Countries of Origin” List,” https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/sites/homeaffairs/files/what-we-do/policies/european-agenda-migration/background-information/docs/2_eu_safe_countries_of_origin_en.pdf.

[12] Patrick Gathara, “Is Kenya at War with Al-Shabab?” Aljazeera, April 28, 2015, https://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/2015/04/kenya-war-al-shabab-150414111433725.html.

[13] GOV.UK, “What the Home Office does,” https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/home-office.

[14] Bosworth, Mary. Inside Immigration Detention. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014.

[15] Refugee Council, “Terms and Conditions,” accessed October 5, 2017 https://www.refugeecouncil.org.uk/terms_and_conditions.

[16] GOV.UK, “Find an Immigration Removal Centre,” https://www.gov.uk/immigration-removal-centre.

[17] Global Detention Project, “United Kingdom Immigration Detention,” accessed January 2, 2019 https://www.globaldetentionproject.org/countries/europe/united-kingdom.

[18] UK Parliament, “House of Commons Wednesday 2 November 2016 Meeting,” accessed May 1, 2017 https://parliamentlive.tv/event/index/ea02bdf2-6876-4fd1-bf87-4368aaf21d85?in=12:28:08.

[19] Yutaka Arai Yokoi, “Grading Scale of Degradation: Identifying the Threshold of Degrading Treatment or Punishment Under Article 3 ECHR,” Netherlands Quarterly of Human Rights 21, No. 3 (2003): 385-421.

[20] Griffiths, Melanie, “Living with Uncertainty: Indefinite,” Journal of Legal Anthropology 1, No. 3 (2013): 263-86.

[21] Izabella Majcher, ibid.

[22] Melanie Gower, “”Asylum Support” Accommodation and Financial Support for Asylum Seekers.” Briefing Paper Number 1909: House of Commons Library (2015).

[23] Global Detention Project, ibid.

[24] Informationsverbund Asyl und Migration, “Germany Country Report,” accessed March, 2018 www.asylumineurope.org/reports/country/germany.

[25] Library of Congress, “Refugee Law and Policy: Germany,” accessed June 21, 2016 https://www.loc.gov/law/help/refugee-law/germany.php.

[26] Rosemary Sales, “The Deserving and the Underserving? Refugees, Asylum Seekers and Welfare in Britain,” Critical Social Policy 22, no. 3 (2002): 456-78.

[27] Louise Waite, “Asylum Seekers and the Labour Market: Spaces of Discomfort and Hostility,” Social Policy and Society 16, no. 4 (2017): 669-79.