Abstract

Although most African migration is voluntary, safe, orderly, and regular, policymakers tend to pander to popular narratives of an irregular “swarm” of African nationals invading the West. African migration occurs primarily within the continent, representing broader processes of political, economic, and social development by contributing to growth rates, promoting regional economic integration, and fostering trade, investment, commerce, knowledge transfer, and human contact. If harnessed properly, migration could further enhance productivity in agriculture, construction, mining, and services within the continent. Despite its potential, however, intra-Africa migration is hampered by restrictive policies including tight controls around visa access, rights of residency, employment, and citizenship for foreign African nationals. This article presents evidence-based scholarly research and policymaking on drivers, patterns and trends in African mobility, and makes concrete suggestions for how policymakers in the continent can design and implement pan-African migration policies that foster development.

Introduction: Why Should Policymakers Develop a Pan-African Migration and Development Agenda?

Migration is a critical driver of socioeconomic development in Africa. A study by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and the International Labour Organization (ILO) in 2018 found that migrant contributions to GDP amounted to 19 percent in Côte d’Ivoire in 2008, 9 percent in South Africa in 2011, and 13 percent in Rwanda in 2012. Current projections indicate that global migration could increase Africa’s GDP per capita from US$2,008.00 in 2016 to US$3,249 in 2030, assuming an annual growth rate of 3.5 percent.[i] Beyond contributing to growth rates, migration is a conduit for promoting regional economic integration. Intra-Africa migration, in particular, “positively impacts structural transformation in destination countries.”[ii] If harnessed properly, it could enhance productivity in a variety of sectors by improving the supply of skilled labor, facilitating knowledge transfer and leveraging the comparative advantage of domestic markets.[iii] Thus, there is a symbiotic relationship between development and migration in Africa: development facilitates migration and migration facilitates development.

Conventional perceptions of African migration tend to focus on the so-called “migration crisis” in the Mediterranean, where sub-Saharan African migrants accounted for 42 percent of the 1,500 migrant fatalities in 2015.[iv] This has prompted donors to concentrate almost exclusively on stemming the flow of irregular African migration to Europe, even though most African migration occurs within the continent. For example, of the 34 million African migrants reported in 2015, approximately 18 million (52 percent) were intra-African migrants; this figure swells to 70 percent in sub-Saharan Africa.[v] Some estimates indicate that the share of African migrants within Africa is 53 percent (19.7 million).[vi] Others show that intra-African migration accounts for a little over 80 percent of all African migration.[vii] Given the restrictions on intra-African migration imposed by African states, policymakers in the continent should seek to enhance the contributions of African migrants to continental growth and socioeconomic development by facilitating freedom of movement.

After 18 months and six rounds of intergovernmental negotiations, the final draft of the Global Compact on Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration (GCM) was adopted widely in July 2018. It is expected that United Nations (UN) member states – including those in Africa – will implement this global, non-legally-binding agreement. Regional pan-African institutions such as the African Union (AU) and the UN Economic Commission for Africa (ECA) have already taken the lead on setting the agenda for enabling safe, orderly, and regular African migration, in keeping with the adoption of the GCM.[viii] This article argues that Africa should focus intently on “maximizing the benefits of migration” through a pan-African migration and development agenda rather than “obsessing over minimizing risks” largely projected onto the continent by outsiders, as notably articulated by UN Secretary-General António Manuel de Oliveira Guterres.

African Migration by the Numbers

Migration Through, To and From Africa

African migration has mushroomed and diversified in the last two decades. Rural-to-urban migration, labor migration, irregular migration, migration of youth under age 30, women migrants, asylum seekers, and internally displaced persons (IDPs) have all increased dramatically.[ix] In 2015, out of 244 million international migrants worldwide, 34 million or 14 percent were born in Africa, with a near-even split by gender. By 2017, there were approximately 258 million international migrants globally, representing 3.4 percent of the world population, with African migrants accounting for only 10 percent of the total migrant population.[x] Pre-colonial, colonial, and post-independence migratory routes continue to shape patterns of movement today, with migrants from Africa attracted to countries with historical, geo-political, linguistic, and cultural ties.

Historically, the top destinations for African migrants have included South Africa, Côte d’Ivoire, Nigeria, Kenya, and Ethiopia. Intra-African migration corridors include Burkina Faso-Côte d’Ivoire, South Sudan-Uganda, Mozambique-South Africa, Sudan-South Sudan, and Côte d’Ivoire-Burkina Faso. These routes link not only major commercial agriculture and mining activities and informal trade routes, but also irregular and forced migration channels.[xi] The top five sources of African migrants are Egypt, Morocco, Somalia, Sudan, and Algeria.[xii]

| Figure 1: Top Ten Sending and Receiving Countries in Africa, by Number of Migrants, 2015 | |

| Top 10 sending countries in Africa |

Top 10 receiving countries in Africa |

| Egypt | South Africa |

| Morocco | Côte d’Ivoire |

| Somalia | Nigeria |

| Sudan | Kenya |

| Algeria | Ethiopia |

| Burkina Faso | South Sudan |

| Democratic Republic of Congo | Libya |

| Nigeria | Uganda |

| Mali | Burkina Faso |

| Zimbabwe | Democratic Republic of Congo |

Source: United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs[xiii]

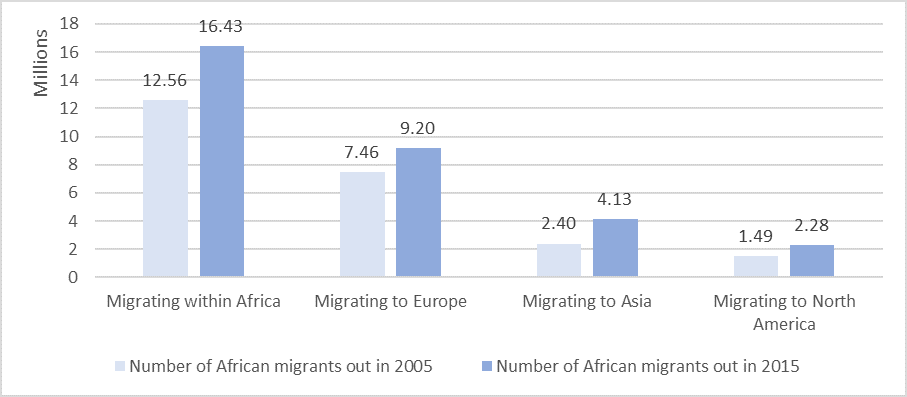

Figure 2: Number of African Migrants by Area of Destination in 2005 and 2015

Source: Population Division of the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs[xiv]

Outside Africa, Europe accounts for approximately 9.2 million African migrants, representing 28 percent of the total African migrant population worldwide.[xv] France, Spain, Italy, and the UK were the most popular destinations for African migrants in Europe in 2017. Outside of Europe, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and the United States attracted the largest number of African migrants.[xvi] Inversely, Africa is becoming a top destination for European retirees and Asian entrepreneurs.

Although fragility and conflict are major drivers of irregular and forced African migration, refugees constitute a relatively small share of the migrant population from the continent. For example, when news about a Mediterranean “migration crisis” dominated headlines in 2016, irregular boat crossings of refugees and labor migrants from Africa were approximately 100,000, about one-seventh of the estimated total regular migration to OECD countries.[xvii] Moreover, unauthorized overland and maritime crossings represent a minority of all migratory flows within and from the continent.

Many exogenous migration-related initiatives, such as the European Union (EU) Emergency Trust Fund for Africa (2015), worth €3.4 billion ($3.9 billion), endeavor to manage irregular migration from Africa by addressing root causes such as poverty, inequality, conflict, unemployment, and underemployment. However, some scholars have argued that efforts to contain migration by addressing these drivers are ineffective because socio-economic development neither curbs citizens’ desires to migrate, nor decreases migration rates.[xviii] Moreover, African countries with higher levels of socioeconomic development, such as those in the Maghreb, coastal West Africa, and South Africa, account for the majority of regular migration out of Africa.[xix] Additionally, in lower- to lower-middle-income countries in Africa, development actually facilitates emigration by making migration costs more affordable and increasing incentives to migrate.[xx] That the poorest of the poor rarely migrate calls into question the tendency to focus policymaking on poverty-induced, irregular migration.

Furthermore, Africans’ motivations for migrating are varied and nuanced; they range from extreme cases, such as the need to flee persecution, violence, and environmental disasters to more mundane motivations, such as a desire to avoid boredom and professional stagnation. Close to 70 percent of African migrants are young and productive, between the ages of 20 and 64. According to the Gallup World Poll of 2015, the share of people who want to migrate is greatest in Africa: North Africa (24 percent), West Africa (39 percent), the rest of sub-Saharan Africa (29 percent).[xxi] Therefore, the challenge for African policymakers is to make Africa a desirable destination for African migrants. To achieve this goal, they should focus not only on “creating jobs, raising standards of living, and eliminating repression and violent conflict” but also on “nurturing foundations of hope” and creating viable “prospects for social mobility and social change.”[xxii]

According to scholars of migration, the focus of policymaking on African migration should be enabling Africans to remain in Africa because they want to, not because they are blocked from migrating elsewhere.[xxiii] Although recent migration work has been framed within the context of fragility and conflict, African policymakers should address not only crisis-induced (forced) or irregular migration (due to political, environmental, or ecological factors), but also non-crisis-induced labor or regular migration. They should adopt different strategies to address migration by engaging with four categories of actual and potential African migrants:

- Those who have the resources to migrate and already have (i.e. diasporas);

- Those who have the resources and have not already migrated;

- Those who do not have the resources and still migrate (whether they fail or succeed);

- Those who do not have the resources and do not migrate, but have the desire to migrate – what Carling describes as “involuntary immobility.”[xxiv]

With respect to this final category of potential migrants, evidence suggests that the inability to migrate may encourage them to pursue other alternatives, such as joining extremist movements. The involuntarily immobile are also less likely to invest in skills enhancement or livelihoods development; this could have unintended consequences for development assistance targeting them.[xxv] For these reasons, policymakers must pay particular attention to this demographic.

How Should African Policymakers Design Migration Policies?

African policymakers should cater to the needs of the four categories of actual and potential African migrants by supporting and financing their mobility, particularly within Africa.

- Research Funding and Capacity Building in Migration Data Analysis

Evidence must be the bedrock of meaningful migration and development interventions. Therefore, African policymakers should fund national statistical offices as well as regional centers for research to facilitate data collection. By gathering robust baseline data on African migrants, disaggregating them by gender, age, country of origin, educational background, socio-economic status, etc., policymakers can better address their needs. In turn, this data should be shared across national, regional, and continental platforms, as well as inform the International Organization for Migration (IOM) Global Migration Data Portal, the World Bank Migration Knowledge Partnership on Migration and Development, and the recently established Multilateral Development Banks’ Platform on Economic Migration and Forced Displacement.

Policymakers on the continent must also work with the AU and ECA to fund the establishment and operationalization of an African Migration Research and Policy Network,[xxvi] comprising African migration scholars and leading policymakers on African migration. The proposed Network should collate scholarly and policy-focused writing on African migration for reference across the continent. Additionally, the Network should build a database of African migration scholars and policymakers who could provide ad-hoc research and policy support on topics as varied as diaspora bonds and the gendered implications of migration. Given that migration creates promising economic opportunities for African women, policymakers in particular should consider commissioning specific studies to inform targeted policies and programs in regional member countries (RMCs) on the gendered dimensions of African migration. For example, policymakers could establish a special fund to provide micro-credit and insurance premiums for women cross-border traders.

- Implementing Africa-Centric Migration Frameworks

Over the last century, Africa has participated in or signed onto international agreements[xxvii] and platforms related to migration.[xxviii] Furthermore, the AU has spearheaded initiatives of its own.[xxix] While these agreements are relevant and important for Africa, there is a lack of political will and limited capacity to enforce them in the continent. In a few unfortunate cases, African governments have signed agreements with non-African institutions that explicitly contravene regional free movement of persons protocols. Nevertheless, the adoption in 2018 of the Protocol to the Treaty Establishing the African Economic Community Relating to Free Movement of Persons, Right of Residence and Right of Establishment[xxx] by 32 RMCs of the AU, as well as the Continental Free Trade Area Agreement (AfCFTA)[xxxi] by 49 out of 55 RMCs, signaled Africa’s renewed commitment to facilitate intra-Africa trade, investment, and mobility.

Although many RMCs have yet to fully ratify and implement the Protocol on Free Movement and the AfCFTA, they remain important instruments for advocacy and financing. African policymakers should assist the AU by ensuring funding to implement migration agreements and platforms instituted from 2015 onwards, specifically the AU-ILO-IOM-ECA Joint Labor Migration Program for Development and Integration (2015), Migration Policy Framework for Africa and 12-Year Action Plan (2017), Protocol on Free Movement (2018), AfCFTA (2018), and Single African Air Transport Market (2018).

African policymakers should domesticate AU migration policies by devising relevant migration strategies of their own, which could include: the protection of migrant nationals abroad (including labor and human rights, evacuation, resettlement and reintegration in times of crisis, etc.); the return and reintegration of migrants fleeing crises in regional and non-regional destinations;[xxxii] the establishment of offices of diaspora affairs in ministries of foreign affairs; the establishment of knowledge transfer programs that would facilitate the return of African nationals with skills suited to fill gaps in the labor market.

- Improving the Flagship Africa Visa Openness Index (AVOI)

Widely referenced in the media for its foresight, the African Development Bank Group’s Africa Visa Openness Index (AVOI) measures the openness of African states to nationals of other countries in the continent. Although it is difficult to prove causation, there is very likely a correlation between the inaugural issue of the AVOI in 2016 and subsequent policy shifts on visa-free intra-African movement. Nearly four years ago, only five countries in the continent had adopted liberal visa policies for all African nationals; that number has now increased to 11.[xxxiii] For example, Benin[xxxiv] and Seychelles allow visa-free travel for all Africans. Senegal now has visa-free access for 42 African countries.[xxxv] After protracted negotiations of more than a decade, in 2017 the Central African Economic and Monetary Community (CEMAC), comprising Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, and the Republic of Congo, agreed to visa-free movement of their citizens.[xxxvi] Similarly, South Africa and Angola agreed to visa-free reciprocal arrangements for each other’s nationals. Ghana, Ethiopia, Kenya, Namibia, and Nigeria were slightly more cautious in vowing to permit visa-on-arrival for all African nationals.

Although African countries are increasingly adopting visa-on-arrival or visa-free travel access to other nationals from the continent, prompted in part by the AVOI, hurdles to achieving a borderless Africa persist. Despite free movement of persons, labor, and services protocols adopted by regional blocs, Africa remains one of the least economically integrated regions of the world and extremely restrictive for intra-African mobility. The AVOI could be leveraged more meaningfully to champion the abolishment of visa requirements altogether (as enshrined in the 2018 Protocol on Free Movement), thereby enabling the rights of entry, residence, and establishment for African nationals in any RMC. To this end, resources allocated for the AVOI could be increased significantly to introduce more robust measures, such as a comprehensive examination of procedural impediments to free movement and statistical evidence on how security has been affected by visa liberalization. An expanded AVOI must also include recommendations for how countries can improve their rankings in subsequent iterations, at least until RMCs can ratify and implement fully the Protocol on Free Movement.

- Funding Skills Enhancement and Portability

African policymakers can assist the AU and ECA to advocate for increasing skills portability, matching skills developed in one country to job opportunities in another. This would conform to the AU’s regional skills-pooling efforts, including the Joint Labor Migration Program (2015) and the Revised Convention on the Recognition of Studies, Certificates, Diplomas, Degrees and Other Academic Qualifications in Higher Education in African States (2014). Skills portability could be achieved by mapping the core competencies of African migrants and depositing this information in a database to help RMCs identify individuals who could meet critical labor market needs across the continent, regardless of their countries of origin. An early version of this database has already proven successful: ECOWAS’ job-matching platform links jobseekers in Benin, Cape Verde, Ghana, Mali, Mauritania, and Senegal to national and continental employment opportunities.[xxxvii]

Skills enhancement and portability would effectively turn “brain drain”[xxxviii] into “brain circulation” within Africa, minimize the youth bulge, and enable young Africans to gain new skills through education and labor mobility. Moreover, African policymakers should target migrant youth in skills development and enhancement thereby assisting them in obtaining internationally recognized workers’ credentials, skills, and qualifications. This would complement the AU’s proposed African Accreditation Agency for developing and monitoring educational quality standards while expanding student and academic mobility across the continent. Furthermore, African policymakers should fund temporary transfer of knowledge programs, similar to the United Nations Development Program Transfer of Knowledge Through Expatriate Nationals (TOKTEN), by bringing back to the continent African diasporas with specialized skills.

- Funding Remittances Platforms

African migrants contribute meaningfully to household incomes in the continent with their remittances, which also serve as an important source of foreign currency reserves.[xxxix] Remittances to Africa currently account for 51 percent of all private capital to the continent, up from 42 percent in 2010.[xl] In 2015, officially recorded remittances to Africa – from outside and within the continent – amounted to US$66 billion, surpassing overseas development assistance and, arguably, serving as a more stable form of financing than foreign direct investment.[xli]

Nigeria is the top recipient of remittances overall in Africa, gaining approximately US$20.8 billion in 2015 alone.[xlii] Liberia holds the top spot for remittances as a percentage of GDP, which accounted for 24.6 percent of GDP during the height of the Ebola outbreak in 2014.[xliii] Despite the significance of remittances to Africa, they are limited as a development tool. First, the poorest households do not receive remittances as they are unlikely to have relatives living abroad. Second, transaction costs for transfers to Africa are higher than for most other regions of the world, and far above the Sustainable Development Goals target of 3 percent.[xliv] Given that many African migrants send transfers through non-formal channels with low to no transaction costs, African policymakers should help to formalize these alternative measures. For example, they could secure and expand highly effective, home-grown remittance facilities such as dahabshil, which faces serious regulatory challenges from anti-money laundering and counter-terrorism financing laws. Alternatively, African governments could subsidize transaction costs by entering into formal partnerships with international money transfer companies such as Western Union and Moneygram, making remittances more impactful in African countries of origin and less expensive for African migrants.

In addition, African policymakers could also fund research on remittance corridors by supporting the work of the African Institute for Remittances (AIR),[xlv] established as a Specialized Technical Office of the AU in 2015. While the EU has committed US$5 million over five years to the Institute, African governments could do more to support its three main goals: reducing the cost of remittances, improving statistical knowledge around services, and better leveraging monetary transfers.

- Expanding Access to Travel Documents

Securing adequate identity documents is a major hurdle for African migrants. African policymakers can help to address this by reducing the cost of biometric national identity documents (such as passports) and civil registry documents (including birth, marriage, and death certificates). These documents are critical in facilitating access to public goods and key services such as healthcare, education, banking, remittance platforms, and emergency assistance. Improving access to travel documents would also provide supplementary benefits by reducing statelessness, contributing to census data collection, and shaping sustainable development planning.

- Supporting Refugee-Hosting Nations

Finally, policymakers should support African countries that host the lion’s share of the continent’s forced migrants by establishing a special fund to augment the national budgets of Uganda, Kenya, Chad, Cameroon, South Sudan, and Sudan. Given the AU’s designation of 2019 as “The Year of Refugees, Returnees and Internally Displaced Persons,” this would invariably integrate refugees, enhance their employability, and enable them to secure land for agricultural productivity.

Conclusion

As continental and regional integration deepen and expand, so too will the movement of African peoples.[xlvi] To that end, African policymakers should channel most, if not all, of their energies on creating an enabling environment for and facilitating regular intra-African migration – including the promotion and financing of inclusive growth, job creation, climate change mitigation, etc. – thereby placing African migrants and their wellbeing at the very center of policy interventions. Policymakers in Africa must also recognize Africans on the move – be they regular or irregular, forced or labor migrants – as resourceful and agentic rather than passive victims of circumstance.

[i] United Nations, Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), Economic Development in Africa Report 2018: Migration for Structural Transformation (New York and Geneva, Switzerland: United Nations, 2018).

[ii] UNCTAD, Economic Development in Africa Report 2018, 102.

[iii] UNCTAD, Economic Development in Africa Report 2018, 102.

[iv] International Organization for Migration (IOM), Fatal Journeys: Improving Data on Missing Migrants (Geneva, Switzerland: International Organization for Migration, 2017).

[v] United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA), Trends in International Migrant Stock: The 2015 Revision (United Nations database, POP/DB/MIG/Stock/Rev.2015).

[vi] UNCTAD, Economic Development in Africa Report 2018.

[vii] African Union, Evaluation Report of the AU Migration Policy Framework (Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: African Union, 2016).

[viii] While the AUC has spearheaded a series of migration-centric initiatives and its Agenda 2063 advocates for the free movement of persons as part of a continental integration agenda, the ECA established in 2016 the High-Level Panel on International Migration in Africa (HLPM) to influence evidence-based policymaking on African migration.

[ix] African Union, Revised Migration Policy Framework for Africa and Plan of Action (2018-2027) (Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: African Union, n.d.).

[x] United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA), Trends in International Migrant Stock: The 2015 Revision (United Nations database, POP/DB/MIG/Stock/Rev.2017).

[xi] UNCTAD, Economic Development in Africa Report 2018; UNDESA, Trends in International Migrant Stock: The 2015 Revision.

[xii] UNDESA, Trends in International Migrant Stock: The 2015 Revision.

[xiii] UNDESA, Trends in International Migrant Stock: The 2015 Revision.

[xiv] UNDESA, Trends in International Migrant Stock: The 2015 Revision.

[xv] African Union, Revised Migration Policy Framework for Africa and Plan of Action (2018-2027).

[xvi] UNCTAD, Economic Development in Africa Report 2018.

[xvii] Economic Commission for Africa (ECA), briefing notes for the High Level Panel on International Migration in Africa, 2018.

[xviii] Jørgen Carling, “How Does Migration Arise?” in Migration Research Leaders’ Syndicate: Ideas to Inform Cooperation on Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration, eds. Marie McAuliffe and Michele Klein Solomon (conveners) (Geneva, Switzerland: International Organization for Migration, 2017), 19-26.

[xix] The reverse trend is true for countries that obtain middle-income or upper-middle-income status, in which emigration decreases with increasing levels of immigration.

[xx] Linguère Mbaye, “Supporting Communities Under Migration Pressure: The Role of Opportunities, Information and Resilience to Shocks,” in Migration Research Leaders’ Syndicate: Ideas to Inform Cooperation on Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration, eds. Marie McAuliffe and Michelle Klein Solomon (conveners) (Geneva, Switzerland: International Organization for Migration, 2017), 91-96.

[xxi] Gallup, “Gallup World Poll,” n.d., https://www.gallup.com/services/170945/worldpoll.aspx.

[xxii] Carling, “How Does Migration Arise?”

[xxiii] Carling, “How Does Migration Arise?”

[xxiv] Jørgen Carling, “Migration in the Age of Involuntary Immobility: Theoretical Reflections and Cape Verdean Experiences,” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 28, no. 1 (2002): 5-42.

[xxv] Carling, “How Does Migration Arise?”

[xxvi] This network would ideally complement and support the previously established Network of Migration Research on Africa, coordinated by leading African migration scholar Professor Aderanti Adepoju.

[xxvii] International conventions that attempt to protect the rights of migrant workers have had minimal success because the majority of high-income countries have not ratified and/or implemented them.

[xxviii] These include the ILO Migration for Employment Convention (1949); ILO Migrant Workers (Supplementary Provisions) Convention (1975); UN Convention against Transnational Organized Crime including the Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons Especially Women and Children, and the Protocol Against the Smuggling of Migrants by Land, Sea and Air (2003); UN Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families (2003); UN High-Level Dialogues on International Migration and Development (2006, 2013); Global Forum on Migration and Development (launched in 2007); the New York Declaration on Migrants and Refugees (2016); Guidelines to Protect Migrants in Countries Experiencing Conflict or Natural Disaster (MICIC Guidelines) (2016); and the IFAD Global Forum on Remittances, Investment and Development (2017).

[xxix] These include the African Common Position on Migration and Development (2006); Migration Policy Framework for Africa (2006); Ouagadougou Action Plan to Combat Trafficking in Human Beings, Especially Women and Children (2006); Joint AU-EU Declaration on Migration and Development (2006); [Kampala] Convention for the Protection and Assistance of Internally Displaced Persons in Africa (2009); Pan-African Forum on Migration (2015); AU-ILO-IOM-ECA Joint Labor Migration Program for Development and Integration (2015); Declaration on Migration (2015); the African Union Passport (2016); Migration Policy Framework for Africa and 12-Year Action Plan (2017); Common African Position on the Global Compact on Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration (2017); Protocol to the Treaty Establishing the African Economic Community Relating to Free Movement of Persons, Right of Residence and Right of Establishment (2018); African Continental Free Trade Area Agreement (2018); Single African Air Transport Market (2018), etc.

[xxx] Sub-regional groups have previously adopted free movement of persons protocols, including the ECOWAS Protocol on Free Movement of Persons (1979); COMESA Protocol on the Free Movement of Persons, especially Labor Services, the Right of Establishment and Residence (1994); and SADC Protocol on the Facilitation of Movement of Persons (1997), amongst others.

[xxxi] To date, Kenya, Ghana, Niger, Rwanda, Chad, eSwatini (formerly Swaziland), South Africa, Guinea, Uganda, Mauritania, and Sierra Leone have ratified the Agreement.

[xxxii] Robtel Neajai Pailey, “Long-Term Socio-Economic Implications of ‘Crisis-Induced’ Return Migration on Countries of Origin,” research brief, Migrants in Countries in Crisis Initiative (Vienna, Austria: International Centre for Migration Policy Development (ICMPD), 2016).

[xxxiii] African Development Bank and African Union Commission, Africa Visa Openness Report 2018 (Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire: African Development Bank Group, 2018).

[xxxiv] Benin was the top reformer in the 2018 AVOI.

[xxxv] Kerry Dimmer, “A Visa-Free Africa Still Facing Hurdles,” Africa Renewal (December 2017-March 2018).

[xxxvi] Dimmer, “A Visa-Free Africa Still Facing Hurdles.”

[xxxvii] UNCTAD, Economic Development in Africa Report 2018, 158.

[xxxviii] An estimated 70,000 skilled African professionals emigrate from the continent each year. African Union, Revised Migration Policy Framework for Africa and Plan of Action (2018-2027).

[xxxix] Robtel Neajai Pailey, “Silver Lining, Silver Bullet or Neither? Post-War Opportunities and Challenges for Liberian Diasporas in Development,” in Liberian Development Conference Anthology: Engendering Collective Action for Advancing Liberia’s Development (Monrovia, Liberia: USAID/Liberia, Embassy of Sweden, and University of Liberia, 2017), 213-230.

[xl] UNCTAD, Economic Development in Africa Report 2018.

[xli] African Union, Revised Migration Policy Framework for Africa and Plan of Action (2018-2027); UNCTAD, Economic Development in Africa Report 2018.

[xlii] World Bank. 2016. Migration and remittances factbook 2016. Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group.

[xliii] World Bank. 2016. Migration and remittances factbook 2016. Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group; Pailey, Robtel Neajai. 2017a. “Liberia, Ebola and the pitfalls of statebuilding: Reimagining domestic and diasporic public authority.” African Affairs 116 (465): 648–670.

[xliv] UNCTAD, Economic Development in Africa Report 2018.

[xlv] The AIR is currently collaborating with six countries – Democratic Republic of Congo, Ghana, Madagascar, Malawi, Mauritania, and Zimbabwe – to devise new policies for minimizing remittance transfer fees.

[xlvi] UNCTAD, Economic Development in Africa Report 2018.

Photo Credit: Brookings, Figures of the Week: Internal Migration in Africa