“Even if the end of time is upon you and you have a seedling in your hand, plant it.”

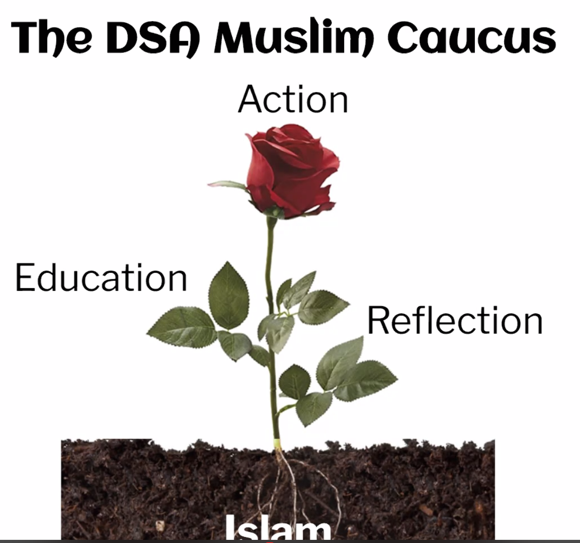

This hadith, or verified quote from the Prophet Muhummad, highlights the inherent value of cultivation in Islam. No matter what the future looks like, we must take tender care of the present—it is never the wrong time to sow the seeds for something beautiful, or nourishing. In spring 2020, after the conclusion of the Democratic primary race and COVID-19 dealt a one-two punch to the personal and political hopes of progressives around the country, many rightfully resigned themselves to just getting through each new day. A few Muslim students, however, had a seed in hand and the heart to plant it.

Inspired by the revolutionary legacy of Malcolm X, students Sirad Hassan, Samy Amkieh, and Abdelhamid Arbab put out a statement calling for a “dedicated group of Muslims within the Democratic Socialists of America,” meant to organize against the chokehold of corrupt and racist capitalist structures. Following the assertion that a truly faithful understanding of the Islamic tradition should motivate Muslims in America to strive for racial, economic, and environmental justice, this DSA Muslim Caucus would focus on issue-based advocacy within the Muslim community. Many heard the call—within months, the group became a Caucus, building toward formal recognition as a “Working Group” within the DSA at large.

Despite the issue-based approach (which favors canvassing for specific policies like Medicare for All over campaigning for any politician), part of this momentum could be ascribed to the fervor of recent electoral politics; the group hopes to apply lessons learned from the Bernie Sanders campaign to a progressive Muslim base that has proven ready to show up. However, in an interview, Hassan points out to me that this base goes further and deeper than has been recognized by those working in electoral politics. She emphasizes that while the “Muslim vote” is often imagined as an Arab or South Asian vote by those in power, Black Muslims have a long history of organizing toward liberation in this country. Despite this, the Muslim community has in no way been immune to anti-Black racism, and the Caucus has made combatting racism within the Muslim community—and standing with the broader national struggle against anti-Blackness—a key priority.

“There’s so much knowledge in Islam that could inform what we now call socialism, and we wanted a space where Muslims can reflect and organize around that,” Hassan tells me. “But we wanted to be intentional and inclusive of all Muslims, who bring their own experiences with race, class, and sect inside and outside the Muslim community to the table.”

This resistance to a monolithic presentation of the American Muslim also informs a drive to take on more than just what some deem “Muslim issues” (like discrimination against Muslims in America, or the occupation of Palestine and Kashmir). Rather than frame Islam as an identity, the DSA Muslim Caucus takes Islam as a unifying ethos, an orientation towards solidarity and justice, a rich tradition of truth-telling and putting the community above the self. From that view, guaranteeing healthcare as a human right is a Muslim issue. Dismantling the prison-industrial complex is a Muslim issue. Fighting for the environment, for workers’ rights, for the dignity of all those violently degraded by American capitalism, American racism, American imperialism—that is a Muslim issue.

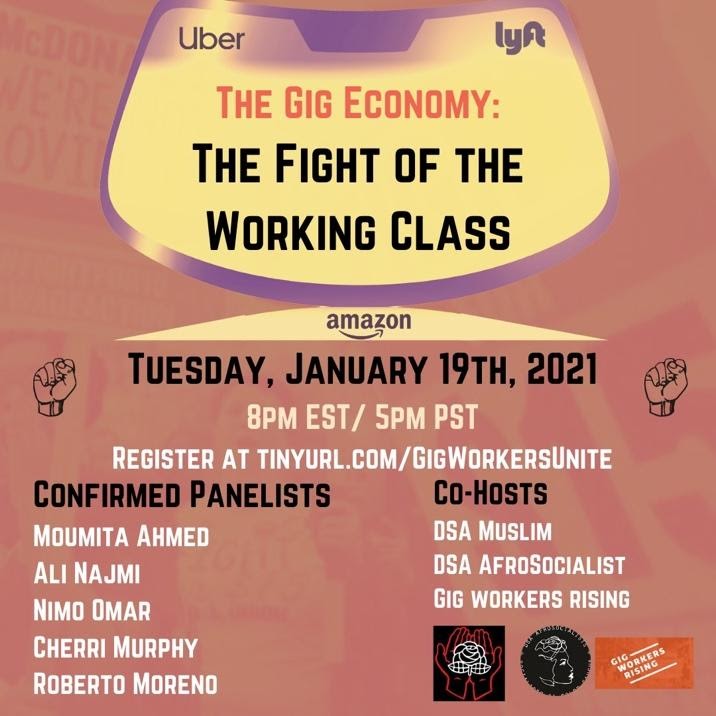

This radical inclusivity has thus far paid off, bringing in members alienated from overwhelmingly white local DSA chapters, but also feeling discouraged from organizing in some Muslim spaces on the basis of gender, race, sexuality, or sect. Dina Benayad-Cherif, a tech worker based in the Bay Area, tells me that the inclusiveness and emphasis on solidarity within the Caucus keep her coming back. “There is no litmus test that makes you a more legitimate member,” Benayad-Cherif says. “You don’t have to prove how ‘Muslim’ you are to be given a platform.” Benayad-Cherif and Hassan (along with other members) are working with the DSA AfroSocialist Caucus and Gig Workers Rising to host an online panel discussion on January 19th called “The Gig Economy: The Fight of the Working Class”. The event is aimed at getting “a stronger grasp of the unique challenges that the pandemic has brought to labor organizing as well as the opportunities it has presented in growing an internationalist workers movement.”

Eschewing identity politics on a shallow level, members of the DSA Muslim Caucus engage in a deeper reflection of what it means to be an American Muslim. Rather than foreground heritage, or the intricacies of beliefs, or even dedication to Islamic practices like daily prayers, the DSA Muslim Caucus asks: what do you stand for? In doing so, they also fill a void currently occupied by right-wing boogeyman fantasies. After decades of red scare and Islamophobic paranoia and the recent memory of Fox News histrionics alleging Obama as both Muslim and socialist, it is no wonder a new generation seeks to challenge the notion that these are bad things to be. In embracing these labels and taking up that space, the DSA Muslim Caucus seeks to broaden the American political imagination about what Muslims can stand for, while also making a case within the Muslim community about what Muslims must stand for.