BY JACK GAO AND DIANA ZHOU

Imagine a world where cars operate on electricity alone. Cars are silent, engineless, odorless. Gas stations are replaced by individual electric charging stations located in homes, offices, and shopping mall parking lots. Roads and pavement use friction technology to charge cars as they drive. In dense urban metropolises like Beijing, Mexico City, and New York City, the air is crystal clear because electric vehicles do not release pollution or particulate matter. People no longer remember the smell of diesel exhaust because even trucks and buses are electric. Sound incredible? It doesn’t to the Chinese government.

In fact, the Chinese government is currently working to make a majority of the nation’s vehicle fleet electric.[i] It has published an official target of five million electric vehicles on its roads by 2020.[ii] Moreover, the government identified New Energy Vehicles (NEVs), a broad category that includes electric vehicles (EVs), as a strategic priority for the State Council in its recent 13th Five-Year Plan, the social and economic development targets released by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) every five years.[iii] However, building and scaling up an industry as complex and capital-intensive as electric vehicles is no easy task. It requires coordination amongst numerous competing factions—private auto manufacturers, state-owned electricity and automotive enterprises, local and national governments, and, most of all, consumers.[iv] The government has failed to bring about this transition before.[v] What would it take to succeed this time? We discuss the rationale for developing EVs in China, reflect on the failures of past policy interventions, and explore two policies the Chinese government should consider to promote the adoption of electric vehicles in the world’s largest auto market.

1. Why China Needs the Electric Car

China faces three urgent challenges as it transitions from a low-cost manufacturing hub to a consumption-driven economic powerhouse: a lack of indigenous innovation, energy dependency, and environmental degradation. The mass-market adoption of electric vehicles would address all three.

First and most importantly, EVs represent an opportunity for China to gain a significant technological advantage over the developed world while driving economic growth.[vi] China fears it will fall into a “middle income trap,” continuously manufacturing low value-added products such as textiles and relying on foreign innovation.[vii] In order to sustain economic growth, the CCP believes it should upgrade its industry to a higher-value, higher-technology role in the global supply chain.[viii] EVs represent a part of this goal, and battery technologies offer an opportunity to “leapfrog” foreign competitors.[ix] Indigenous innovation in this sector would help China create new domestic jobs, build a large domestic market, and develop globally competitive products for export.[x] In this way, China’s EV industry could surpass other developed world auto sectors while driving sustainable economic growth.[xi]

EVs also provide a promising solution to China’s energy dilemma.[xii]China is already exposed to significant risk in its energy supply, which is expected to grow as energy demand increases by a predicted 4.8 percent per annum until 2020.[xiii] Today, approximately 60 percent of the country’s oil is imported, with over 80 percent of this coming from the Middle East.[xiv] Much of this oil is imported for vehicle use. According to the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, new vehicle sales made up as much as 70 percent of China’s annual growth in gasoline and diesel consumption in 2013.[xv] Given increasing geopolitical uncertainties in the Middle East as well as the South China Sea, through which much of China’s imported oil travels, it is critical for the nation to reduce oil dependence.[xvi] By transitioning to EVs and away from conventional fuel vehicles, China can greatly reduce its exposure to risks in the global oil markets.[xvii]

Finally, EVs have the potential to reduce carbon emissions and air pollution. In 2010, China recorded almost 1.3 million deaths from air pollution, more than twice the amount in all countries within the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) combined.[xviii] Vehicles are a major source of pollution and carbon emissions.[xix] For example, vehicles in Beijing accounted for nearly a third of local emissions of PM2.5, a type of fine particulate matter which is one of the leading causes of respiratory diseases.[xx] Because widespread adoption of EVs will shift pollution and emissions from vehicles in urban centers to electricity generation plants located in less-densely populated areas, EVs can significantly cut air pollution and reduce health risks in cities.[xxi] Moreover, the possibility of transitioning from coal to renewables or less dirty forms of energy generation means the switch to EVs can further reduce China’s overall carbon and pollutants emissions.[xxii]

2. A Failed Transition

While a transition to EVs appears beneficial, shifting millions of consumers to a new technology has proven difficult for the Chinese government. Since the early 2000s, China has implemented a series of policies aimed to develop a domestic EV market.[xxiii] However, these interventions have failed thus far to meet targeted goals for several reasons.

As of the beginning of 2016, most government policies on EVs have focused on prioritizing consumer incentives. For example, in 2009, the Ministry of Finance selected 13 cities, including Beijing and Shanghai, for a pilot program offering subsidies of up to RMB 60,000 (USD 9,370) for the private purchase of battery electric vehicles.[xxiv] Many cities matched these federal subsidies, which together could cover up to 60 percent of purchase prices, and then went even further, rolling out administrative incentives to encourage EV adoption.[xxv] For example, starting in 2015, Beijing exempted electric vehicles from its infamous car license lottery system and odd-even number plate alternation policies in which residents could only drive in the city on certain days of the week.[xxvi] Similarly, Shanghai waived EV buyers the approximately RMB 85,000 (USD 13,000) license plate fee and two-year wait that is typical among traditional car buyers.[xxvii] By mid-2015, the government had spent an estimated RMB 37 billion (USD 5.8 billion) on the EV ecosystem, mostly on purchase subsidies and tax reduction and exemption policies, in an attempt to make EVs attractive to consumers.[xxviii]

The results of these policies are mixed at best. On the one hand, many government-owned vehicle fleets have transitioned to EVs. [xxix] For example, in 2014, China procured almost 30,000 electric buses, surpassing the United States and Japan to top the global ranking of electric bus fleets.[xxx] Adoption rates for passenger vehicles, however, have been underwhelming. In 2012, the State Council announced consumer purchase targets of 500,000 pure electric and hybrid vehicles by 2015 and 5 million units by 2020.[xxxi] As of December 2015, only approximately 220,000 EVs were on the road in China.[xxxii] Missing such an important target by more than 50 percent is a rare and embarrassing event for a planning state with a track record of exceeding development goals. Why did these policies fail despite strong government support? We posit two explanations.

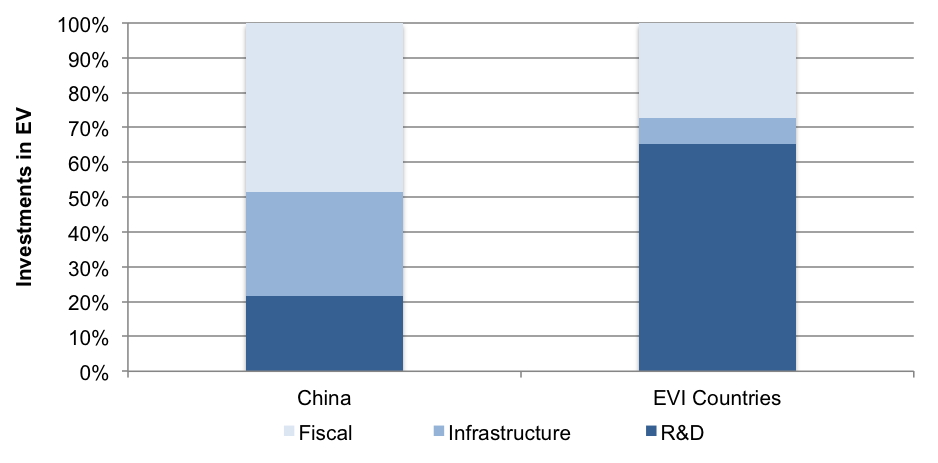

Figure 1: Major Areas of Investment by China and EVI Countries to Build Up the EV Ecosystem

Source: McKinsey & Company[xxxiii] and IEA[xxxiv]

Firstly, the government did not focus enough on EV product development.[xxxv] Instead, the regime poured money into consumer subsidies to encourage EV adoption.[xxxvi] As can be seen in Figure 1, nearly 50 percent of the government investment in the EV ecosystem was spent on consumer subsidies and tax reductions, compared to only 21 percent on research and development.[xxxvii] In contrast, countries participating in the Electric Vehicle Initiative (EVI), a global policy forum dedicated to accelerating worldwide adoption of EVs, spent approximately 65 percent of their budget on R&D and only 30 percent on consumer subsidies.[xxxviii] Relying primarily on consumer purchase subsidies is extremely costly and unsustainable in the long-run, especially if consumers become dependent on these subsidies for product uptake. Moreover, these subsidies do not address the underlying market problem: creating a product consumers want in the absence of government incentives.

Secondly, the government did not invest enough in a robust charging infrastructure network. According to a recent McKinsey & Company study, only 32 percent of the charging stations and 7 percent of the charging poles the Chinese government targeted for construction by the end of 2015 had been completed by April 2015.[xxxix] This failure likely stems in part from the top-down efforts of the Chinese government to create charging infrastructure through its two state-owned electricity utility companies, China State Grid and China Southern Grid, which have been asked to foot the bill without an obvious business model.[xl] Installing charging poles by itself is not a profitable endeavor—meager revenues from electricity usage are unlikely to outweigh the costs of installation.[xli] As a result, the state-owned enterprises have dragged their feet and delayed building charging stations.[xlii] Additionally, accessibility to what charging infrastructure exists is problematic.[xliii] Many charging facilities are located in areas away from cities where land is relatively cheap rather than in urban centers where consumer demand is high.[xliv] This misalignment in incentives slows the pace of building charging stations, dissuading urban consumers from purchasing EVs and hurting overall uptake.[xlv] With the government determined to increase the penetration of EVs and prepared to develop supporting measures, more is at stake than ever before in this market.

3. Avoid Throwing Good Money After Bad

China’s 13th Five-Year-Plan presents an opportunity to implement a new set of policies to facilitate the widespread adoption of EVs.[xlvi] To capitalize on this occasion, planning authorities must understand why past interventions have failed and craft policies that will better incentivize consumer purchases of EVs. We posit two policy solutions.

First, the government should create a targeted incentive structure for EV and battery manufacturers to spur investment in research and technology. This should be accompanied by manufacturer subsidies. Currently, China has no concrete targets for the performance of key EV component technologies.[xlvii] In contrast, the US Department of Energy plug-in electric vehicle program sets detailed targets for battery costs, vehicle weight, and other systems costs.[xlviii] The Chinese government should follow this example and set subsidy amounts to incentivize EV manufacturers to reach predefined goals, e.g., creating lighter vehicles or producing more-efficient, higher-quality batteries at a reduced cost. Battery investments are especially critical and should be a focus of government intervention as battery and related management systems make up as much as 45 percent of the total cost of EV production.[xlix] The government should hold manufacturers accountable by regularly monitoring research progress to prevent fraud. The regime should also fine manufacturers if they miss their targets. This combination of clear research targets, subsidies, and measures of accountability should help improve underdeveloped EV technologies and make EVs more attractive to consumers.

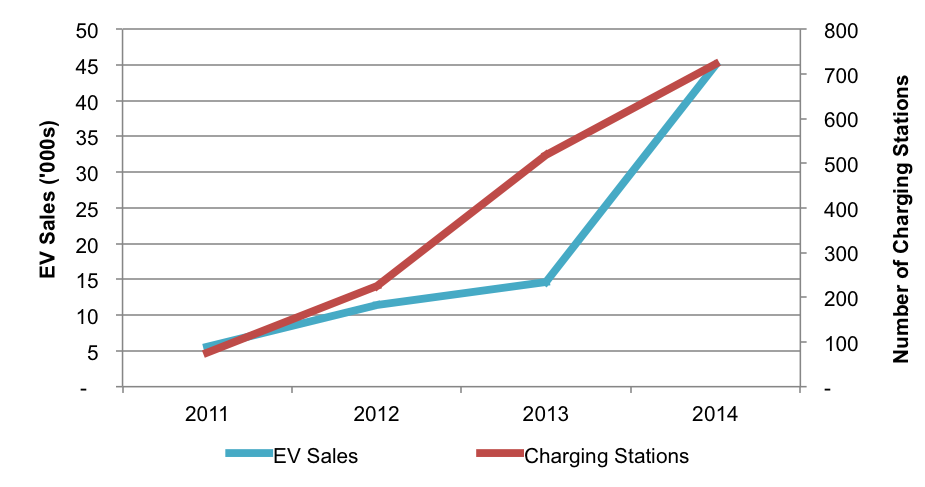

Figure 2: The Number of Charging Stations and Pure EV Sales in China in 2011–2014

Source: Wind Economic Terminal[l]

Second, the government needs to increase the number of charging stations and charging poles. As Figure 2 shows, EV sales are closely related to the number of charging stations.[li] Without more charging stations, it simply does not make sense for Chinese consumers to purchase a vehicle that they may not be able to reliably charge and operate. The government should focus its efforts in urban areas where consumer demand is highest.[lii] As 80 percent of total charging demand comes from homes, workplaces, or public parking lots, the government should coordinate with real estate developers to create cheaper, more-widely-available charging points in homes and workplaces.[liii] A special challenge in major Chinese cities such as Beijing and Shanghai is the fact that much of the population lives in very dense xiaoqu apartment complexes, where parking is limited and designated parking spots are costly or nonexistent.[liv] The government should pay particular attention to providing more charging options for xiaoqu residents to help spur EV purchases among average Chinese consumers. The government should also seek to forge partnerships with private companies that can contribute to building a robust charging infrastructure network, as relying on its two state-sponsored electricity enterprises alone has proven insufficient.[lv] By offering tax breaks for the installation of charging stations and poles, the government can incentivize companies to construct more charging stations. The regime can also frame such a partnership as an opportunity to be perceived as an environmentally-conscious company. By increasing private sector involvement, the government can help supplement its own efforts and provide a much-needed boost in consumer confidence.

Conclusion

Will China be able to transition into an era of pollution-free electric vehicles? On the one hand, China’s history of successful central planning and policy implementation makes it seem likely. On the other hand, this push has failed once before.[lvi] Generating widespread EV adoption will not be easy with the technological and infrastructure problems that China faces. However, given the potential benefits outlined above, it is a task worth pursuing for the Chinese government. As the world’s largest automobile market, China’s successful transition to electric vehicles would have dramatic implications for the nation and the world.[lvii] Moreover, such a transition would showcase a new model of green innovation as China looks to venture into more sophisticated manufacturing.[lviii] Armed with the interventions outlined above, China can make strides toward expanding the EV market, boosting sustainable domestic production and consumption, and demonstrating to the world that a central planning economy can successfully drive one of the most important shifts in consumer behavior in the twenty-first century.

Photo credit: dove lee via Flickr Creative Commons

[i] Nicholas Olczak, “China remains a rocky road for electric cars,” China Dialogue, 17 November 2015. https://www.chinadialogue.net/article/show/single/en/8302-China-remains-a-rocky-road-for-electric-cars

[ii] C. Custer, “China’s government wants 5 million electric cars on the roads by 2020,” Tech in Asia, 19 February 2015. https://www.techinasia.com/chinas-government-5-million-electric-cars-roads-2020

[iii] Angela Fan, “Three Reform Strategies Behind Xi’s Energy Revolution,” The US-China Business Council, accessed 26 February 2016. https://www.uschina.org/three-reform-strategies-behind-xi%E2%80%99s-energy-revolution

[iv] Christopher Marquis, Hongyu Zhang, Lixuan Zhou, “China’s Quest to Adopt Electric Vehicles,” Stanford Social Innovation Review, Spring 2013, 52.

[v] Axel Krieger, Philipp Radtke, and Larry Wang, “Recharging China’s Electric-Vehicle Aspirations,” McKinsey & Company, July 2012. http://www.mckinsey.com/industries/automotive-and-assembly/our-insights/recharging-chinas-electric-vehicle-aspirations.

[vi] Sabrina Howell, Henry Lee, and Adam Heal, “Leapfrogging or Stalling Out? Electric Vehicles in China,” Harvard Kennedy School Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, May 2014, 16. http://belfercenter.ksg.harvard.edu/files/EVs%20in%20China.pdf

[vii] Ibid., 10.

[viii] Ibid., 11.

[ix] Ibid., 11.

[x] Ibid., 11.

[xi] Adam Minter, “To See the Future of Electric Cars, Look East”, Bloomberg View, 10 December, 2015. http://www.bloombergview.com/articles/2015-12-10/to-see-the-future-of-electric-cars-look-east

[xii]Sharon Burke, “China’s Energy Security”, New America Weekly, 14 May, 2015. https://www.newamerica.org/weekly/chinas-energy-security/

[xiii] Development and Research Center of the State Council of China and Shell Global. Research on China’s Medium and Long Term Energy Development Strategy, China Development Press, 2013, p. 11.

[xiv] EIA, “US Energy Information Administration, China.” 2015. https://www.eia.gov/beta/international/analysis.cfm?iso=CHN

[xv] Howell, Lee, and Heal, “Leapfrogging or Stalling Out,” 11.

[xvi] Owen Daniels and Chris Brown, “China’s Energy Security Achilles Heel: Middle Eastern Oil”, The Diplomat. http://thediplomat.com/2015/09/chinas-energy-security-achilles-heel-middle-eastern-oil/

[xvii]Arthur Neslen, “Electric cars could cut oil imports 40% by 2030, says study”, The Guardian, 10 March, 2015. http://www.theguardian.com/environment/2015/mar/10/electric-cars-could-cut-oil-imports-40-by-2030

[xviii] OECD, The Cost of Air Pollution: Health Impacts of Road Transport, OECD Publishing, 2014, p 49.

[xix] Sustainable Transport in China. “Transport said to be responsible for one-third of PM2.5 pollution in Beijing”. http://sustainabletransport.org/transport-said-to-be-responsible-for-one-third-of-pm2-5-pollution-in-beijing/

[xx] Ibid.

[xxi] Howell, Lee, and Heal, “Leapfrogging or Stalling Out,” 12.

[xxii] Ibid.

[xxiii] William Pentland, “Why China May Save The Electric Car”, Forbes, 27 October, 2008. http://www.forbes.com/2008/10/27/china-electric-cars-biz-manufacturing-cx_wp_1027electric.html

[xxiv]China Government, “Four Ministries Select 13 Pilot Cities for Energy-Saving and New Energy Vehicles (in Chinese)”, 17 February, 2009, http://www.gov.cn/jrzg/2009-02/17/content_1234317.htm

[xxv] Xinhua. “Shanghai issues first free plates for new energy vehicles.” http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/china/2013-01/23/c_132123502.htm

[xxvi] Rose Yu, “Electric Vehicles to Get Free Rein on Beijing Roads”, The Wall Street Journal, 21 May, 2015. http://blogs.wsj.com/chinarealtime/2015/05/21/electric-vehicles-to-get-free-rein-on-beijing-roads/

[xxvii] Xinhua. “Shanghai issues first free plates for new energy vehicles.” http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/china/2013-01/23/c_132123502.htm

[xxviii] Paul Gao et al. “Supercharging the Development of Electric Vehicles in China.” McKinsey & Company. April 2015. http://www.mckinseychina.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/McKinsey-China_Electric-Vehicle-Report_April-2015-EN.pdf?5c8e08.

[xxix] Minggao Ouyang, “Current Situation and Prospect for New Energy Vehicles in China (Chinese Powerpoint Presentation).” 2015.

[xxx] Ibid.

[xxxi] Howell, Lee, and Heal, “Leapfrogging or Stalling Out,” 10.

[xxxii] Kenneth Rapoza, “For Electric Cars, China Becoming Major Market For the Poor Man’s Tesla.” Forbes. December 7, 2015. http://www.forbes.com/sites/kenrapoza/2015/12/07/for-electric-car-sales-china-becoming-the-poor-mans-tesla/#5d54d81f61a5.

[xxxiii] Gao, Paul et al. “Supercharging the Development of Electric Vehicles in China.” McKinsey & Company. April 2015.

[xxxiv] Clean Energy Ministerial, Electric Vehicle Initiative, IEA. “Global EV Outlook Understanding the Electric Vehicle Landscape to 2020.” April 2013

Note China expenditures include RMB 15 BN in purchasing subsidy and RMB 3 BN in tax reductions and exemptions since the 8th Five Year Plan; EVI countries include the United States, United Kingdom, France, Spain, Portugal, Denmark, Sweden, Finland, the Netherlands, Germany, Italy, China, India, South Africa, and Japan. These figures represent spending across all countries during 2008 – 2012.

[xxxv] Levi Tillemann, “Magical Thinking, Why China’s shining promise as a major electric vehicle producer fell short”, Slate, 3 February, 2015. http://www.slate.com/articles/technology/future_tense/2015/02/the_spectacular_failure_of_china_s_electric_car.single.html

[xxxvi] Michelle Florcruz, “China Increases Subsidies On Energy-Efficient Vehicles, But Is It Enough To Alleviate Pollution?”, International Business Times, 19 May, 2015. http://www.ibtimes.com/china-increases-subsidies-energy-efficient-vehicles-it-enough-alleviate-pollution-1929627

[xxxvii] Paul Gao et al. “Supercharging the Development of Electric Vehicles in China.” McKinsey & Company. April 2015. Clean Energy Ministerial, Electric Vehicle Initiative, IEA. “Global EV Outlook Understanding the Electric Vehicle Landscape to 2020

[xxxviii] Clean Energy Ministerial, Electric Vehicle Initiative, IEA. “Global EV Outlook Understanding the Electric Vehicle Landscape to 2020”, April 2013. https://www.iea.org/publications/globalevoutlook_2013.pdf

[xxxix] Gao et al. “Supercharging.”

[xl] Howell, Lee, and Heal, “Leapfrogging or Stalling Out,” 32.

[xli] Daniel Chang et al. “Financial Viability of Non-Residential Electric Vehicle Charging Stations,” UCLA Luskin Center for Innovation, August 2012.

[xlii] Howell, Lee, and Heal, “Leapfrogging or Stalling Out,” 32.

[xliii] Gao et al. “Supercharging.”

[xliv] Ibid.

[xlv] Ibid.

[xlvi] Bloomberg News, “China Seen Stepping Up Push for Electric Cars in Five-Year Plan,” Bloomberg, 29 September 2015. http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-09-29/china-seen-stepping-up-push-for-electric-cars-in-five-year-plan

[xlvii] Brendan Clift, “Batteries may stall China’s electric vehicle push”, South China Morning Post, 21 December, 2015. http://www.scmp.com/business/companies/article/1893674/batteries-may-stall-chinas-electric-vehicle-push

[xlviii] U.S. Department of Energy, “EV Everywhere Grand Challenge Blueprint.”, January 2013. http://energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2014/02/f8/eveverywhere_blueprint.pdf

[xlix] Zhang Qian, “Getting Out of EV Cost Trap (In Chinese)”, CCID Consulting, 24 March, 2014. http://www.ccidconsulting.com/article/20140324/3923.html

[l] Source: Wind Economic Terminal, accessed 13 January 2015. http://www.wind.com.cn/en/product/Wind.WET.html

[li] Ibid.

[lii] Gao et al., “Supercharging,” 18.

[liii] Gao et al., “Supercharging,” 17.

[liv] Interviews with experts in the automotive industry in Shanghai, China, in January, 2016.

[lv] Nigro, “Business Models.”

[lvi] Krieger, Radtke, and Wang, “Recharging China’s Electric-Vehicle Aspirations.”

[lvii] Patricia Jiayi Ho, “China Passes U.S. as World’s Top Car Market,” The Wall Street Journal, 12 January, 2010. http://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052748703652104574651833126548364

[lviii] Economist, “Still Made in China, Chinese Manufacturing Remains Second to None”, 12 September, 2015. http://www.economist.com/news/special-report/21663332-chinese-manufacturing-remains-second-none-still-made-china