As a record number of Americans file for unemployment and families struggle to make ends meet, the COVID-19 Pandemic has not only accentuated deep flaws and inefficiencies in the U.S. healthcare system; it has also exposed gaping holes in America’s social safety net. In response, U.S. policymakers must act boldly to construct a new social contract—one that encompasses healthcare and economic security for all citizens—just as past leaders seized crises to remake American society for the better.

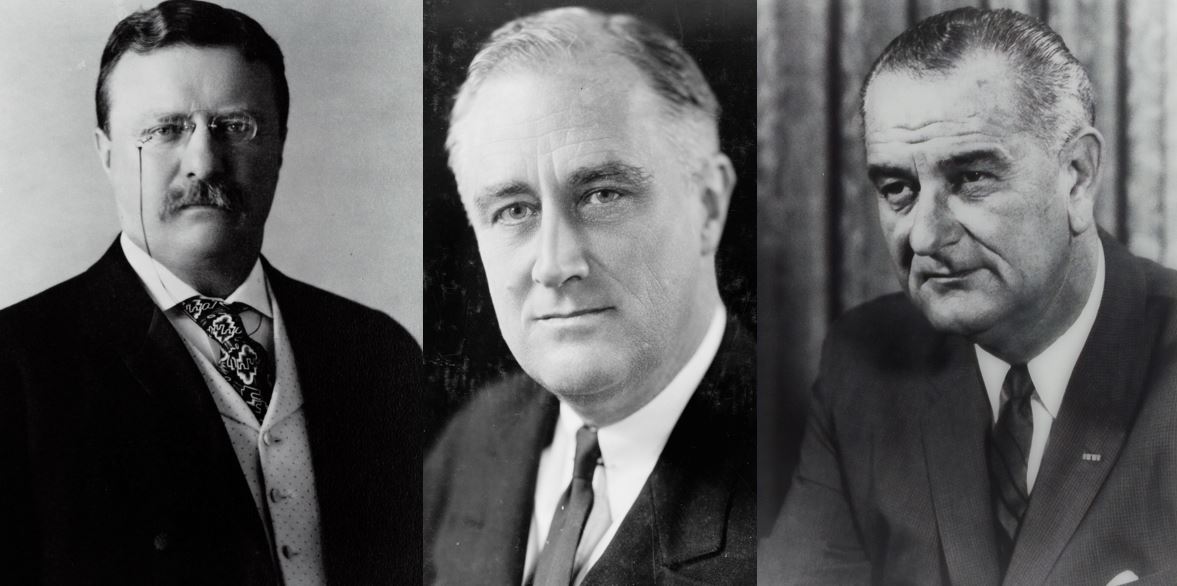

It is difficult to imagine what the United States would look like without unemployment benefits, social security, universal K-12 education, school lunches, food stamps, and Medicare and Medicaid. We take these programs for granted and millions of people rely on them for basic human necessities. Less appreciated, however, is the fact that these programs did not exist a century ago, and were only introduced after periods of severe hardship exposed our government’s inability to protect the most vulnerable segments of society. Whether it was the horrific labor practices that ushered in the Progressive Era, the economic collapse that led to President Roosevelt’s “New Deal,” or the violent opposition to civil rights and stubborn persistence of poverty that motivated President Johnson’s “Great Society,” each of these terrible episodes acted as a catalyst for meaningful reforms that improved the lives of countless Americans.

Yet, in 2020, a staggering number of Americans still lack access to healthcare, economic inequality is at an all-time high, and the U.S. has one of the highest rates of childhood poverty among all developed countries. Some have pointed to these depressing facts as proof that government can do little to solve society’s thorniest problems, but the truth is that the U.S. has not done nearly enough. Government-minimalists ignore parts of the world where a more robust social contract has resulted in higher quality of life, improved health, greater civic engagement, and a vibrant and more equitable capitalist system.

According to a study published by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington, the U.S. ranked 27th in the world in the provision of healthcare and education, well behind top-ranking European and Asian democracies with more capable government institutions. These countries also have higher rates of voter participation (and therefore democratic accountability), spend far more on retraining programs for the unemployed, and score much higher on measures of wellbeing and happiness.

Unsurprisingly, as it turns out, a healthy, happy, and well-educated labor force is also a boon to a free-market economy. It is no coincidence that Forbes puts the U.K., Netherlands, Sweden, Denmark, South Korea, and more than ten other democratic nations ahead of the U.S. in its annual “Best Countries for Business” list. Even the conservative-leaning Heritage Foundation puts sixteen other nations ahead of the U.S. on its economic freedom index. The U.S. gets in the way of its own success by not investing nearly enough in its population’s potential.

While America has let critical government infrastructure atrophy, other nations have gone in the opposite direction by investing in universal healthcare and a modern social safety net, and COVID-19 has made it abundantly clear who is better equipped to deal with today’s health and economic crises. Fiscal stimulus packages and monetary policy, while helpful in the short-term, simply do not provide the structural reform needed to bring America in line with its peer democracies, and leave our country just as vulnerable when the next crisis hits.

After the worst has passed, the next U.S. President must work with Congress to introduce a public health insurance option for all citizens and start laying the groundwork for a universal healthcare system, including affordable child and elderly care. It is unthinkable that millions of Americans routinely choose not to see a doctor out of fear of medical bills and bankruptcy; COVID-19 has only exacerbated this problem. Before the federal government forced insurers to provide emergency coverage, sick Americans avoided testing and treatment out of fear of the cost, likely spreading the virus to others. Those without insurance—including at least 20 million recently-fired Americans—must continue to make the barbaric choice between their health and financial solvency. America’s abysmal COVID-19 death rate and lethargic response to testing have also demonstrated that, all else being equal, nationalized healthcare systems can be mobilized and coordinated much more quickly than our current patchwork system of private institutions.

Equally as important, we must bring our antiquated labor laws into the 21st century, starting with statutory sick and family leave for all workers. America is the only developed nation not to guarantee paid sick and family leave for its citizens, which means that for weeks people with COVID-19 symptoms continued to spread the virus to their coworkers and customers because they could not afford to miss a paycheck. Many essential workers face this same dilemma today.

While Congress acted in a laudably swift and bipartisan manner to pass the CARES Act (including the Paycheck Protection Program), this legislation should be viewed as a temporary bandage and not a replacement for structural reform. In order to aggressively counter mass unemployment and make it easier for businesses to restart operations after a public health emergency or similar crisis, the U.S. should establish an emergency paycheck guarantee or furlough assistance program to cover businesses’ payroll costs. Money would be distributed through existing IRS channels, then paid directly from businesses to employees, avoiding many of the inefficiencies that have plagued current stimulus efforts. There has also never been a better time to introduce a federal jobs guarantee, which would simultaneously stimulate the economy while mobilizing a civilian army to build field hospitals and clinics, provide much-needed services for disabled and elderly Americans, and boost national contact tracing capacity.

Previous attempts to update America’s social contract have only succeeded when a crisis laid bare its glaring weaknesses. Given the current state of America’s entrenched political system, historians may look back on this pandemic as the event that allowed the U.S. to finally shake its habitual polarization and enact urgently-needed reforms. Just like stopping the virus, preserving our nation’s health and well-being becomes harder the longer we wait.

Ethan Gauvin is a graduate student at the Harvard Kennedy School of Government and MIT Sloan School of Management, where he studies the future of work and capitalism.

Edited by: Derrick Flakoll

Photo by: Library of Congress