BY DENISE LINN

Recently, while we’ve all been busy binge-watching House of Cards, our cable companies and online content providers have been splashed across the headlines. The announced $45 billion Comcast-Time Warner Cable merger and the Netflix-Comcast deal have flooded the Internet with articles about pricing, speed, and customer satisfaction. While sources have speculated about how these new business relationships might impact the average customer, there are different, more relevant questions to pose: How might further consolidation of the Internet distribution market impact the average citizen? Even if we are not their customers, why should we care about these companies’ activities from a policy perspective?

If you are part of the 70 percent of Americans with a home broadband connection, then the primary way you interact with your service provider is likely through dollars and cents on your monthly bill. Unfortunately, as many consumers know, the source of that bill is usually a matter of geographic destiny rather than competition or choice. For those of us in Cambridge, that bill is sent by Comcast. If you’re in Los Angeles or North Carolina, it’s likely from Time Warner Cable. If you live in Kansas City, it might come from Google Fiber.

We open, read, pay and complain about those bills as customers, but we consume the product as citizens. Speed and quality impact your ability to learn, create, share and participate politically in the Digital Age. As a majority of job postings, mainstream news outlets, and essential government services move exclusively online, the country needs an accessible, competitive communications system.

Will the marriage of Comcast and Time Warner Cable meet our civic needs in the 21st Century? After a completed merger, Comcast will increase its subscribership by almost 50 percent and will dominate 19 of the 20 largest television markets in the country. This larger cable company will wield a huge amount of market power to negotiate with television channels, set packages and prices, and steer innovation (or a lack thereof) in the years to come. According to recent rankings, the U.S. is now 35th in the world for Internet speed and 58th for Internet pricing. In other words, compared to other developed countries, the U.S. pays more for less. Ironically, about a week after the prospective merger announcement, newcomer Google Fiber released news of a proposed expansion to 9 new metro areas on top of their current projects in Kansas City, Provo, and Austin. Neither Comcast nor Time Warner has made strides of this speed and scope.

How can we be expected to compete in the global economy with an oligopolistic telecommunications market and inferior infrastructure? This is a question that affects us all—not just Comcast and Time Warner customers.

The natural market incentives built into the telecommunications industry are not conducive to producing the type of communications system American citizens demand or deserve. With a collection of local monopolies and duopolies, dominant companies face little incentive to invest in speed, but a large incentive to prioritize their own content holdings on the networks they run. For instance, as of 2011, Comcast is no longer just Comcast; they merged with NBC Universal, creating a new vertically integrated company that has a stake in the success of the channels, films, and online videos produced by NBC. Visiting Harvard Law Professor Susan Crawford, author of Captive Audience, described the threatened media system recently to NPR:

“Comcast is in the business of competing with the Internet at this point. They want to make sure that you don’t get Internet access other than through them, and that their own partners get preference over their giant digital pipes. They have no particular interest in making sure that Americans get very, very fast, very high capacity Internet connections, because they’d like their own video to do better.”—Susan Crawford

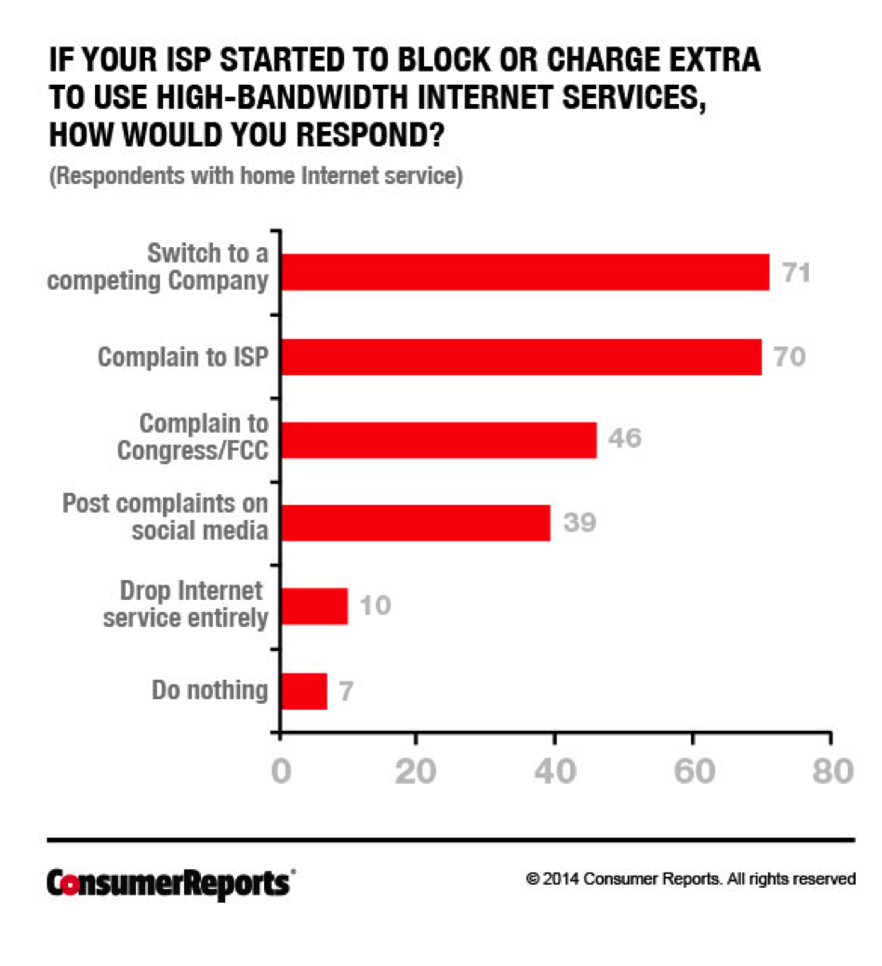

In a recent survey conducted by Consumer Reports,

Unfortunately, discriminating video content is not the worst-case scenario from a citizen’s perspective. If companies like Comcast can preference certain video content over competitors, then they could legally preference other kinds of businesses and content over others. What if, in a new tiered online content system, your cousin’s policy blog wasn’t as accessible as Ezra Klein’s? What if, due to a private business agreement with your Internet service provider, Amazon.com loaded faster than a local business’ website? Just recently, Netflix agreed to pay Comcast to ensure smoother streaming. This new business relationship between content providers and network providers sets a troubling precedent and, ultimately, the consumers may lose out in the long run. Going forward, we will see if end users will absorb a portion of Netflix’s raised costs.

So, the next time you open your Internet bill, remember that, aside from the balance listed along the bottom, there are policy implications to the service you pay for each month. The business relationships that are accepted, regulated, or blocked in this field will shape the future of the Internet and your digital experience as a consumer and citizen.

Photo source here.