Abstract

The modern Middle East is a complicated formation of states, each with its own distinct history, religious identity, and relationship to the colonial powers. In non-academic circles, it is commonly assumed that each state has existed in roughly the same autonomous territory since antiquity; and colonialism, while harmful, merely briefly interrupted that long chain of independence, leaving no scars. This essay seeks to dispel that notion through an analysis of the European diplomatic engagements that pulled apart existing territories and forced them between the borders of new states, sealing a nearly inevitable destiny of domestic strife. Through that analysis, this essay derives a new Middle East diplomacy, dedicated to learning from the past to create a mutually-beneficial future.

Introduction

A quick perusal of the front pages of the Middle East’s newspapers, saturated with mentions of economic frailty, ethnic tension, and endless war, will leave the unfamiliar reader with one question: how did we get here? A weakened Syria struggles beneath the boot of an autocratic regime. Lebanon is torn asunder by sectarianism. And Palestine, drenched with the blood of its people, is occupied by an army of colonists. The answer to this complicated question lies somewhere between the years of 1914 and 1922, when old empires were disintegrating and new ones were imagined into existence in the drawing rooms of Downing Street and Villa Devachan, Sanremo.

Tracing the lines that were haphazardly drawn in pencil and pen on an empty map, and understanding the diplomatic maneuverings that led to their realization, allows one to grasp the poisoned roots of the political conflicts that exist in the Middle East today. The San Remo Resolution, and its precursor, the secretly signed Sykes-Picot Agreement, reveal not just how the colonial powers infused the Middle East with instability and division during the Great War, but also how the region can be revitalized, old dreams can be realized, and the colonial powers, humbled by history, can finally make amends.

Colonial Priorities for the Post-War Order

Long before Rauf Orbay, the Ottoman delegate to the British, signed the Armistice of Mudros in October of 1918, concluding hostilities in the Middle Eastern theatre, the British and the French privately coveted pieces of the rapidly decaying Ottoman empire. To stake their claims, the two powers convened in secret in May of 1916 at Downing Street to sign the infamous Sykes-Picot Agreement. The British, represented by cartoonist Mark Sykes, expressed interest in the Suez Canal for the access it provided to India, and Mesopotamia for its oil. In exchange, it was agreed that Lloyd George would give France, represented by Georges Picot, a quarter of the oil profits, the interior of Syria, and a large swath of the Lebanese coast. The agreement pleased the French, who saw themselves as protectors of the area’s Christian communities; but as soon as the deal was signed, the British began to regret it. They wanted Palestine, recognizing its proximity to Suez, and they resented France’s appropriation of Mosul.[i]

Chaim Weizmann, a leader in the emerging Zionist movement, was similarly intent on securing territorial promises from the British government. Like the French, Weizmann did not come to the negotiation table empty-handed: during the shell shortage of 1915, he had invented a process to mass-produce acetone, the key ingredient for munitions production in woefully short supply. Weizmann’s contributions to the war effort not only led to a scientific appointment with the British government, but also secured him a favor from Lloyd George, the Secretary of State for Munitions.[ii]

Months later, when Lloyd George stood for election to the Prime Ministership, Weizmann saw an opportunity to call in his favor, and began to petition Lloyd George for support of the Zionist cause. Determined to pay his debt, Lloyd George consented.[iii] After winning election in 1916, he opened formal negotiations between the Foreign Office and Zionist leadership, the result of which was the infamous Balfour Declaration of 1917. In the declaration, the British publicly promised the Jewish people a national home in Palestine, sealing the fate of the remaining Ottoman territories in only sixty-seven words.[iv]

Arab Dreams and Broken Promises

Despite British commitments to both the Zionists and the French, as early as 1915, Sir Henry McMahon had promised Hussein, Sharif of Mecca, that if the Arabs revolted against the Ottoman empire, the British would grant them independence.[v] Land from Palestine, Syria, and Mesopotamia would be theirs upon which to consolidate an Arab state. Buoyed by these promises, and entirely unaware of the ongoing negotiations with France and the Zionists, Faisal, King Hussein’s son, boldly launched a revolt against the Ottomans on June 10, 1916. Two years later, Faisal and his troops entered Damascus, breaking the Ottomans’ four-hundred-year grip on the eastern Arab world.[vi]

Before the dust had settled on the city, Faisal began building the state he had been promised, restoring electricity, organizing police patrols, and establishing government posts. To address internal divisions, Faisal granted Ottoman veterans amnesty, and declared that the new Arab government would “treat alike all those who speak Arabic, regardless of sect or religion, and not discriminate in its laws between Muslim, Christian, and Jew.” By the summer, Faisal’s administration had built a government upon these promises, employing thirteen thousand civil servants.[vii]

In the areas beyond Faisal’s early kingdom, leaders from Aleppo, Homs, and Jerusalem began to reorganize the Syrian Union Party (SUP), convening in support of Faisal’s government and a greater Arab state stretching from Aleppo in the north to Jerusalem in the south. SUP leaders even drafted a constitution, guaranteeing the equality of all Syrians before the law.[viii]

Faisal boarded a ship for the Paris Peace Conference on November 22, determined to present this new democracy to the Allies; yet Faisal did not know that Britain and France had formally confirmed their commitment to Sykes-Picot the day before he had seized the city. Further, in December, days before Faisal arrived in Paris, Clemenceau and Lloyd George agreed upon further modifications: Britain would add Mosul to Mandatory Iraq and take Palestine, in exchange for French control over Lebanon and Syria.[ix]

The Making of the Modern Middle East

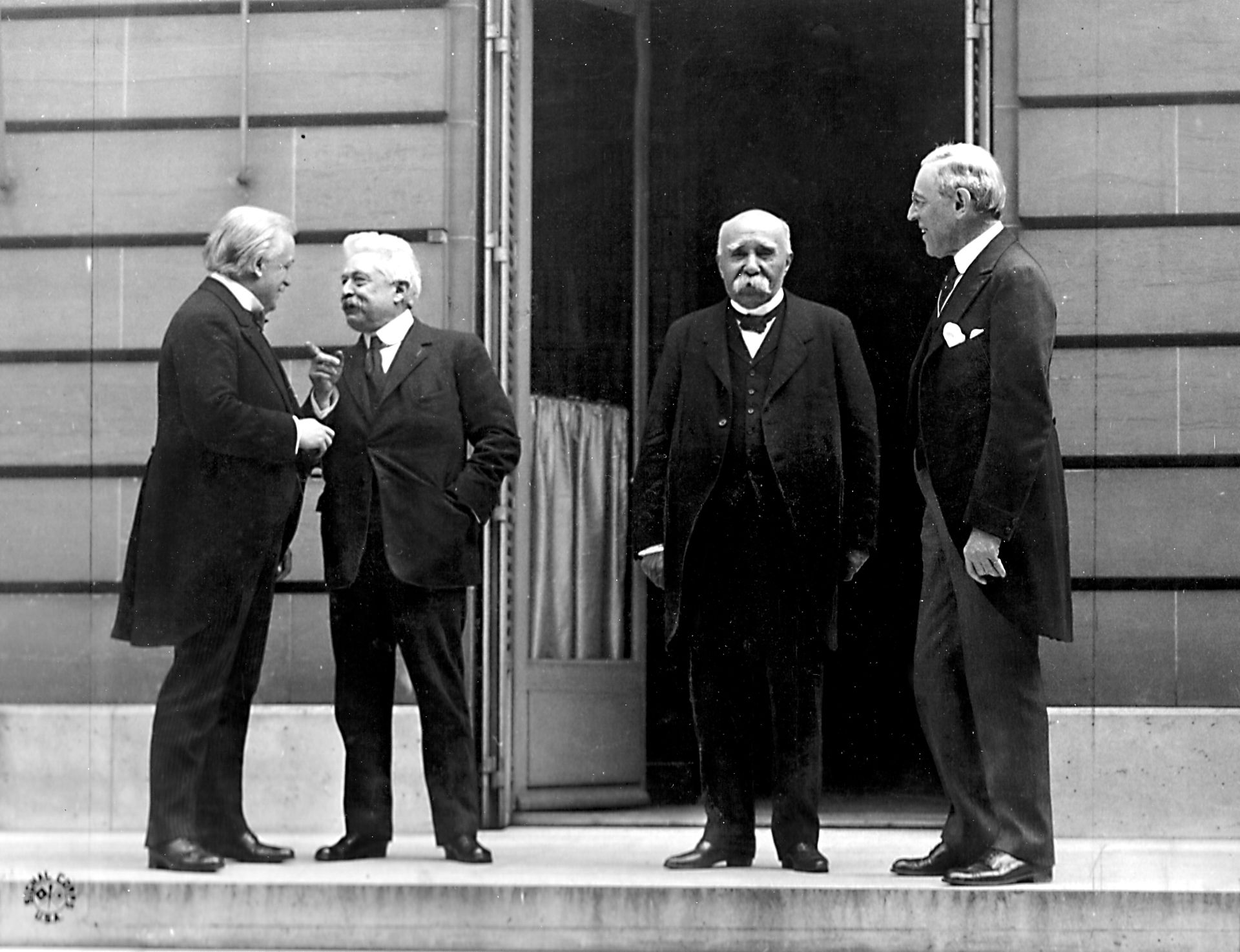

At the Paris Peace Conference, delegates from more than thirty nations gathered to construct a new world order. As the waters of the Seine rose from heavy rain, Wilson’s principle of ‘self-determination’ filled the city with hope. With the support of the American President, it appeared the world was on the precipice of a new democratic age, in which all countries would finally be treated as equals. Despite Wilson’s idealism, the secret promises of Clemenceau and Lloyd George carried the day. In Wilson’s words, “the old order of the world is reasserting itself consciously and unconsciously. The rights of Syria and similar countries are in danger.”

After enduring months of petty indecencies, unequal treatment, and outright racial discrimination, Faisal was forced to leave Paris in April of 1919 without any guarantee of independence. Yet, one glimmer of hope remained: the Allied powers had agreed to send a commission to poll local opinion on the boundaries of a future colonial mandate in Syria, and the choice of mandatory power. Wilson even promised that no permanent settlement would be made without the report.

Henry King and Charles Crane presided over the Inter-Allied Commission on Mandates, visiting towns across Syria and Palestine. By July, the commissioners were aware that the Muslim majority in Syria favored independence, for they had collected nearly two thousand petitions, and more than seventy percent demanded full independence. Recommending that limits be placed on Zionist settlement, the commissioners concluded that “Syria offers an excellent opportunity to establish a state where members of the three great monotheistic religions can live together in harmony.”[x]

The report spoke the same truth that Faisal had presented to the Allies all along, but by the time the commissioners reached Damascus, it was too late. The Big Four had agreed to sign the Versailles Treaty in late June, nearly a month before the Commission had even finished its polling. Wilson’s principle revealed itself to be a platitude, his anxieties a prophecy. In April of the following year, the Allies convened at Villa Devachan, San Remo, to sign the San Remo Resolution, determining the final fate of the Ottoman provinces. In the resolution, the Allies outlined that Britain would administer Iraq and Palestine, and France would occupy Syria. The League of Nations, dominated by the British and the French, ratified the agreement, dividing Greater Syria between the two powers “until such time as they are willing to stand alone.”[xi]

A Shaky Foundation for Peace

When the League of Nations approved the mandate system in December of 1924, neither Lebanon nor Iraq existed. Lines on the map were redrawn, according to the haphazard markings of Sykes-Picot, forcing an incompatible melange of disparate provinces—each with their own distinct identities—into the boundaries of a new state. In Lebanon, the Maronite Christians who had once hid in the mountains now constituted a majority of the population, with Sunni and Shia Muslims resting in a comfortable minority. In Iraq, half the inhabitants were Arab, while the rest were Kurds, Persians, or Assyrians. And in Palestine, the population was majority Muslim; yet as Jewish immigration increased following the Balfour Declaration, Palestinian autonomy diminished.

The disjointed nature of the mandate system not only weakened the Middle East, but also led to internal conflict, leaving the region vulnerable to foreign influence, intervention, and exploitation. As a famous book title put it, the Allies foisted upon the Middle East A Peace to End All Peace, a curse which haunts the Arab lands to this day.[xii]

A New Middle East Diplomacy

The justifications for colonial occupation, whether employed in Paris or San Remo, were consistently rooted in orientalist tropes of Arab incompetence. The British and the French argued that only they could administer the region because the Arabs were not ready to rule themselves, despite the well-publicized efficacy of Faisal’s democracy. It is important for European diplomats to recognize that the Arabs were capable of self-government long before the colonial powers arrived, and they have proven self-sufficient long after they left.

Irrespective of public justification, the European statesmen of the day were not motivated by the pull of ethics, nor by the promise of a lasting peace, but by the prospect of returning money to the imperial treasuries. As a result, the world that they created was deeply flawed, for it was realized to the benefit of only a handful of states. Diplomacy must be rooted in empathy, and its objective must be the collective resolution of global crises, not the selfish accumulation of prestige.

Symbiotic, multilateral relationships will remain unachievable without Wilson’s ever-elusive ingredient of self-determination. The Arab world must be allowed to define itself, unsullied by false perceptions, and determine its own destiny, unimpeded by intervention. If western nations continue to prioritize self-interest over symbiosis, the wounds of old crimes will only fester, and the crises of the modern world will remain unsolved. Just over a century has passed since the San Remo Resolution was signed, yet it is still unclear if the Allies have finally learned from the lessons illuminated by those fateful years, when the whole world waited, with bated breath, for the new world order to be drawn into existence.

[i] MacMillan, Margaret. Paris 1919. Random House, 2001.

[ii] Weizmann, Chajim. Trial and Error: The Autobiography of Chaim Weizmann. 1972.

[iii] George, Lloyd David. War Memoirs. Simon Publications, 2001.

[iv] Nagle, Jeffries Joseph Mary. The Balfour Declaration. Institute for Palestine Studies, 1969.

[v] McMahon, Henry, and Hussein. Correspondence between Sir Henry McMahon, His Majesty’s High Commissioner at Cairo and the Sherif Hussein of Mecca, July 1915-March 1916 (with a Map). Stat. Off., 1939.

[vi] ROGAN, EUGENE. Fall of the Ottomans: The Great War in the Middle East, 1914-1920. PENGUIN BOOKS, 2022.

[vii] Thompson, Elizabeth F. How the West Stole Democracy from the Arabs: The Syrian Arab Congress of 1920 and the Destruction of Its Liberal-Islamic Alliance. Atlantic Monthly Press, 2020.

[viii] Karsh, Efraim, and Inari Karsh. Empires of the Sand: The Struggle for Mastery in the Middle East, 1789-1923. Harvard University Press, 2003.

[ix] MacMillan, Margaret. Paris 1919. Random House, 2001.

[x] Howard, Harry N. The King-Crane Commission: An American Inquiry in the Middle East. 1963.

[xi] Rogan, Eugene L. The Arabs: A History. Penguin Books, 2018.

[xii] Fromkin, David. A Peace to End All Peace: The Fall of the Ottoman Empire and the Creation of the Middle East. Avon Books, 1990.