By Chrissie Long, Staff Writer

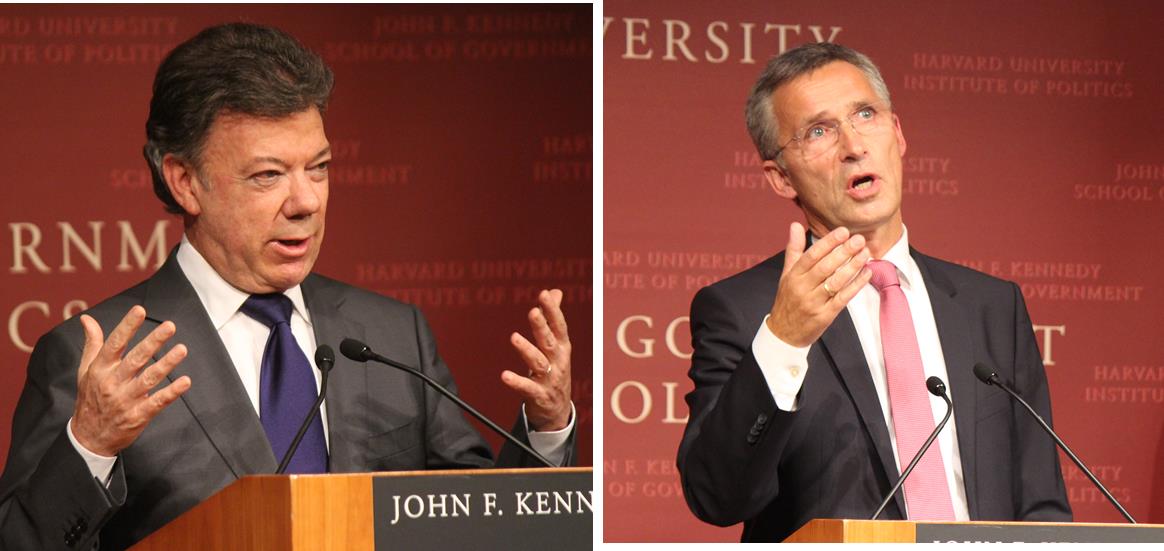

The heads of state of Colombia and Norway spoke at the Harvard Kennedy School on Wednesday night. Both came to Cambridge following the 61st proceedings of the General Assembly of the United Nations last week in New York.

For Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos Calderón, it was a bit of a homecoming. Santos graduated from the Kennedy School’s mid-career master in public administration program in 1981, and returned to Harvard as a Nieman Fellow in 1988.

Pointing to the risers above the forum, he said, “What I learned here, I’ve been applying throughout my life.”

Though Norway Prime Minister Jens Stoltenberghad never spent time at Harvard, he admitted to being an aspiring academic who “got stuck” in politics for 22 years.

Both heads of state – while facing different challenges in their home countries –described how they used their experience as finance ministers to exercise fiscal restraint and move their country toward greater sustainability.

For Santos, it meant eliminating tax breaks for the wealthy and improving tax collection while simultaneously investing in education and infrastructure.

When he took office in 2010, he said Colombia was the ”most unequal country in Latin America.” Though the gap between rich and poor has not entirely closed, he said, “the trend is now positive.”

Santos said his greatest challenge has been ending Colombia’s 50-year war with guerrillas – a struggle he has tackled through peace negotiations rather than force.

Though he admits that “it’s much easier to wage war than to try to win peace,” Santos said he is optimistic that successful negotiations will “liberate the real potential” of Colombia.

Laura Cepeda, a student in the Harvard Kennedy School’s master of public administration/international development program who is from Colombia, was disappointed that Santos “almost sole[ly]” focused on “showcasing” the policies of his government.

“While he did address some of Colombia’s problems—high inequality, violence, largest number of displaced population—he didn’t acknowledge the difficulties his government is having in enforcing laws,” Cepeda said.

She said that one challenge has been the restoration of land to the population displaced by years of conflict and violence.

“This is a critical issue if we are thinking about a negotiated peace with the guerrillas,” Cepeda noted.

Juan Pablo Remolina, an HKS master in public administration student who is also from Colombia, said he appreciated the discussion on negotiations with FARC because many are anxious about the process.

But he agreed with Cepeda on the desire for greater discourse, explaining, “Selling the country in every situation inhibits us to have more open and hard debates.”

The Case of Norway: Avoiding the Oil Curse

While Santos emphasized the need to increase tax revenue to improve the economy, Prime Minister Stoltenberg said the Norwegian government needed to spend less to achieve economic stability.

Norway also needed to avoid the so-called “Dutch disease,” in which countries with a wealth of natural resources often spend themselves into economic crisis. The term comes from the economic troubles that plagued the Netherlands in the 1960s as a result of the discovery of large national gas deposits in the North Sea.

To avoid a similar fate, Stoltenberg said, Norway’s leaders resolved to save by directing all oil profits to a national fund, which the government could access only to obtain the returns.

“It took political courage,” Stoltenberg said, explaining it was difficult to confront Norwegians and tell them they had to continue paying taxes when their country was sitting on a massive surplus. Nor was it easy to explain losses when the economy (and the fund) took a nosedive in 2008.

Aside from its wealth of oil and gas, Norway’s success can also be attributed to efficiency of government operations and a strong labor force, Stoltenberg said, adding that Norway has some of the highest female participation rates in the labor force in the world.

Measured in economic return, “women are a greater investment in Norway than oil and gas,” Stoltenberg said half-jokingly.

In a question-and-answer session following Stoltenberg’s lecture, several audience members asked how other countries rich in natural resources could achieve similar success to Norway.

Noting that “all countries have different histories and experiences,” Stoltenberg said, “I don’t believe countries can copy one another … [but] they can inspire one another.”

Stoltenberg was pressed by the audience to say more.

“There are definitely lessons to be learned,” he said. “At least one of those lessons is not to spend so much money.”