BY MAX NATHANSON

The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) will change Pakistan. CPEC — a proposed network of highways, power plants, and Special Economic Zones (SEZs) worth a reported $62 billion — is set to bring Pakistan more than double the entire volume of foreign direct investment that the country received since 2008. But who, exactly, will benefit in Pakistan?

Islamabad thinks CPEC, proposed by Beijing in 2013, will spark unprecedented economic growth in Pakistan. The election platform of now-Prime Minister Shahid Khaqan Abbasi centered exclusively on CPEC; his party, the Pakistan Muslim League (PML), even branded their campaign in green and red to celebrate Sino-Pakistani friendship. The PML’s CPEC Center of Excellence, housed in the government-run Pakistan Institute of Development Economics, churns out publications extolling the nationwide benefits of CPEC. It isn’t just the PML, though; the powerful Pakistani military and the main opposition parties also all support CPEC. A Gallup poll found that 85% of Pakistanis believe CPEC is important for Pakistani development.

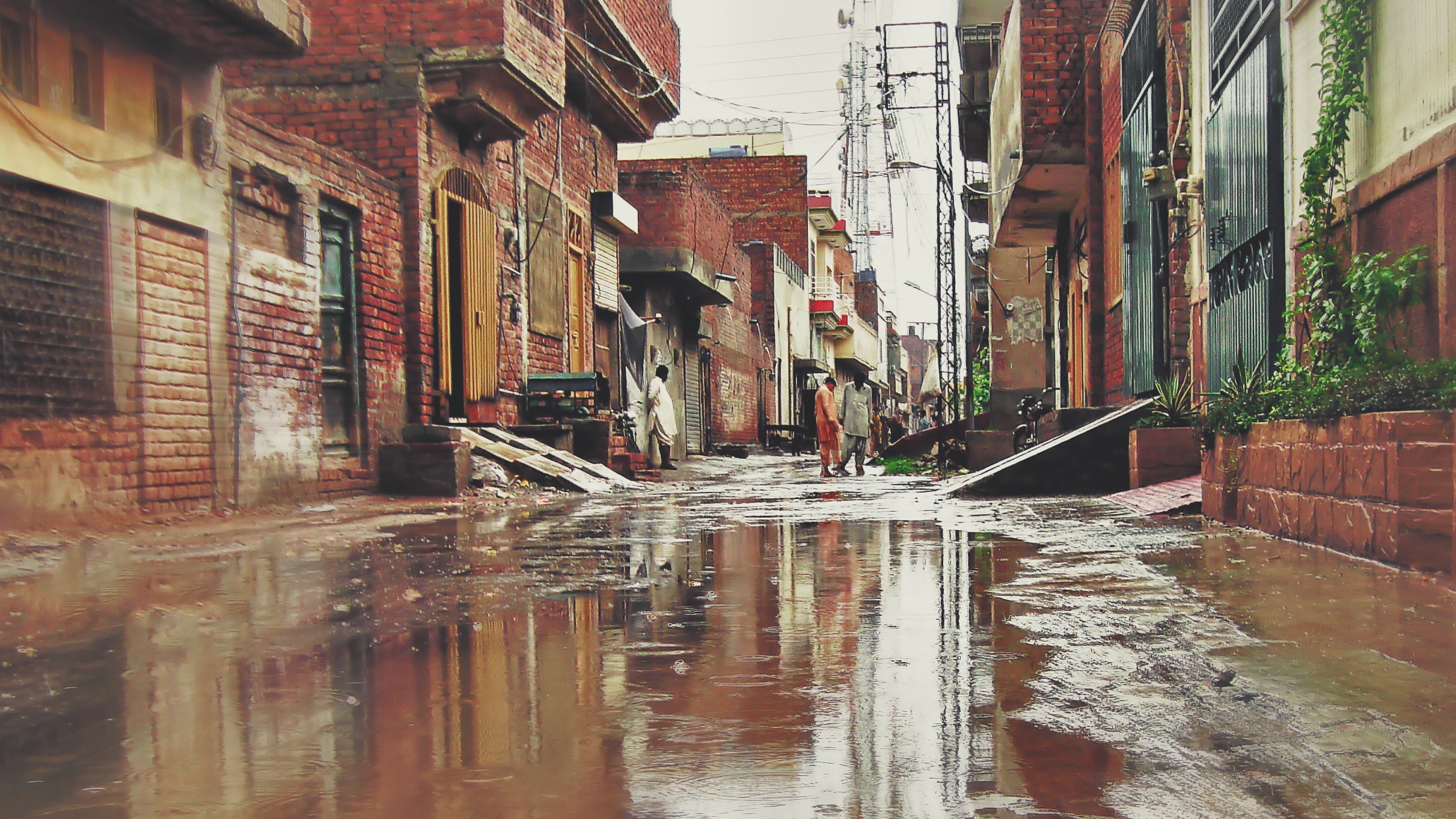

It is easy to understand why CPEC excites so many in a country that has long struggled to develop. Since relations with the US soured in 2007, foreign investment has languished due to weak security, political mistrust, and massive refugee inflows. Pakistan, a country with a strong agricultural heritage, lacks the infrastructure and urban populations necessary to increase productivity in low-skill manufacturing or build higher value-added industries. Its export focus on low value-added textiles has barely changed since 1970. CPEC, as the narrative goes, will promote connectivity, crowd in additional foreign investment in nine proposed (tax-free) SEZs, alleviate reliance on Western lenders, and stabilize the erratic energy supply.

It is also easy to understand why China called CPEC the flagship venture in its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), a multi-trillion-dollar infrastructure initiative that aims to link Eurasian markets more tightly with Beijing. CPEC provides direct road and rail routes from western China to Pakistan’s deep-water port in Gwadar, which has been leased to state-owned China Overseas Port Holding Company (COPHC) for 40 years. Thus, CPEC allows China to reduce its dependence on trade routes through the Malacca Strait, lower transit costs for traded goods, and increase diplomatic pressure on its geostrategic rival India. CPEC also provides more leverage for China to seek cooperation with Pakistan to root out Uyghur dissidents who seek refuge and support with the Pakistani Taliban in the north of the country. Pakistan has created a special force of 10,000 soldiers dedicated to protecting CPEC projects in this vulnerable area.

China’s pursuit of its interests abroad is not necessarily a cause for concern, but CPEC presents serious risks for Pakistan. If CPEC is not managed carefully, Chinese loans could exacerbate Pakistan’s fiscal vulnerability, SEZs could provide anti-competitive tax havens for China’s state-owned enterprises, and deliver benefits only for the PML, which has rushed to complete the first round of ‘early harvest’ projects in time for elections later this year. I argue that CPEC faces three key challenges to truly spark sustainable and inclusive development in Pakistan.

First, China and Pakistan must embrace transparency and accountability. Few details of the CPEC agreement have been made public; the man responsible for negotiating CPEC from the Pakistani side, Interior Minister Ahsan Iqbal, has thus far refused to release details of the CPEC Long-Term Plan (LTP). The financial terms of credit lines, the geography of the proposed route, the actors responsible for drawing up the route, the purpose of the SEZs, environmental impact assessments, and potential resettlement issues all remain secret.

Second, China and Pakistan must take proactive steps to ensure that the planning process emphasizes linkages to local economies. Connective infrastructure on its own does not generate economic growth; CPEC, from its route to the locations of SEZs to financial terms, must be designed to ensure that Pakistani industries and populations will benefit. Research by the Center for Strategic and International Studies showed that only 7.6 percent of companies involved in BRI projects are local; 89 percent are Chinese. A recent Lahore School of Economics conference, which sought to identify and promote industrial clusters that could be ripe for upgrading as a result of CPEC, while ensuring that gender equality and environmental conservation are considered, provides a model of the questions that Pakistanis should ask of CPEC.

Third, China and Pakistan must ensure sound macroeconomic management during CPEC implementation. A recent study by the Center for Global Development listed Pakistan as at ‘high risk’ of ‘debt distress’ due to CPEC financing. But the last thing that Pakistan needs is another plunge into the grasp of foreign creditors. Islamabad must avoid leasing its own development, by chasing large credit lines and shiny new infrastructure with a high risk of indebtedness, to China and allowing Beijing to create a profitable and strategic enclave at Pakistan’s expense.

CPEC’s equity challenges arise from both international and domestic imbalances. China’s economic clout could create asymmetrical terms in everything from project location to credit line structures. The dynamics of Pakistani politics mean that CPEC could become a rent-seeking opportunity for PML-military elites and actually undermine future development. With proper planning and accountability, CPEC could lay a stable economic base for Pakistan to springboard to stronger growth and development. If not, however, and early warning signs prove prescient, CPEC could prove to be an economic and political boon to China and Pakistani elites that bypasses the greater good for Pakistanis.

Max Nathanson is a graduate student in Oxford’s Department of International Development, and a freelance photojournalist. He is co-president of the Oxford Urbanists and was named a Global Shaper by the World Economic Forum in 2017. His writing has been published by the Thomson Reuters Foundation, Mongabay, China Dialogue, and other international outlets. Follow him on Twitter @TheMaxNathanson. The author would like to thank the Lahore School of Economics for its generous support in making participation in their annual conference possible.

Edited by Neil Thomas