Along with the democratic deficit and the breakdown of public order, one strand of recent writing on Middle Eastern and North African (MENA) politics has focused on a perceived need to “rewrite the social contract”, addressing citizen grievances that Arab governments are failing to provide employment opportunities and social safety nets.

Research programs at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government and the World Bank have emphasized a failing “social contract” as the neglected dimension of analysis focused on the region, while the topic makes frequent appearance in region-wide appraisals such as a comprehensive effort by the Carnegie Endowment last year.

To be sure, issues of security, representation, and prosperity are thoroughly entangled across the region – there can be no broad prosperity without a degree of security, while questions of how to hold governments accountable for any new social contract necessarily raise questions of representation.

Of the three various frames for studying the MENA region at present, though, questions of securing economic development and reforming social welfare programs generally receive less attention than topics such as Islamism, security sector reform, or social mobilization. Most analysts, while having some idea of what more representative government or a reduction in violent conflict in the region might look like, understandably struggle to imagine the kind of economic improvement that could curb high levels of unemployment (especially among the educated) and generate much-needed revenue to finance state services such as education, health care, and basic infrastructure projects.

One of the most ambitious, well-defined reform plans in the region for reigning in state obligations to citizens while boosting private-sector development is Saudi Vision 2030, a program of economic and social (but not political) change headlined by the Kingdom’s much-profiled Crown Prince Muhammad bin Salman. Discussions of the hype and potential hypocrisy regarding Vision 2030 have informed much coverage of the Kingdom since 2015, while commentary on the Crown Prince’s reform efforts often claims – as Bernard Haykel recently argued in the pages of the Washington Post, or as Yaroslav Trofimov noted last year in comparing Kuwaiti and Saudi reform efforts – that economic change on such a massive scale all but requires authoritarian rule to force reforms through.

While the Kingdom does not presently face the breakdown in public order or empty state coffers that have kept most reforms to ad-hoc adjustments in other MENA countries, even as the legacies of an oil-based economy pose challenges all their own, the processes by which Vision 2030 is implemented and amended have much to tell us about the politics of retrenchment in the region and elsewhere. This and a subsequent article will examine the dynamics of pulling off such a transition.

Rentier Bargains in the Eyes of Citizens

For Saudi Arabia and most of the region’s resource-rich countries, social contracts between rulers and ruled is typically framed as a “rentier bargain,” a hydrocarbon-fueled subset of the benefits-for-loyalty “authoritarian bargains” scholar Tarek Yousef has theorized as a means of understanding state-society relations in the region.

In a simple model of “no taxation, no representation,” the monarchy and the government around it use the “rents” of vast oil and natural gas to provide comfortable lives for Saudi citizens through handouts and public-sector jobs, who in turn acquiesce to government policies so long as their material needs are provided for.

Of course, reality is more complex. Justin Gengler has ably criticized the notion of a standard “rentier bargain” by demonstrating starkly different understandings of state-society relations among Bahrain’s Sunni and Shia communities – the former closer to a loyalty-for-benefits scheme, the latter rooted far more in demands for equality and justice.

Likewise, a host of scholars have focused on the Kingdom’s discontents over the years: from jihadists and disaffected youth to Islamists, modernizing reformers and the Kingdom’s Shia minority.

Still, the general relationship sketched out by rentier theory appeared to hold in 2010 – the year of the sole publicly available polling data on Saudi Arabia. In this nationally representative poll, conducted by the Arab Barometer project, interviewees reported their views on their household income – broadly, whether household income covered expenses – regardless of how much they actually earned.

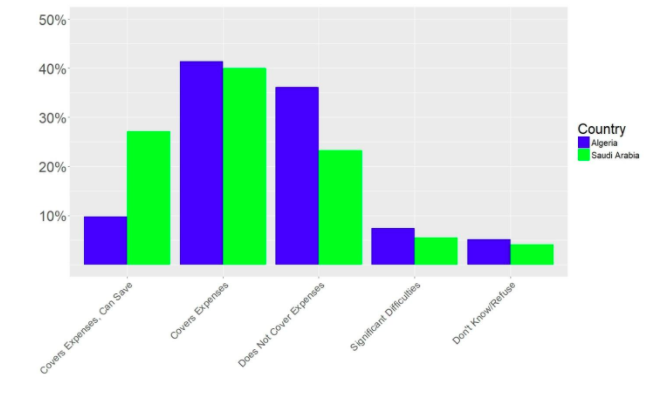

Figure 1: Respondent views of family economic situation, Saudi Arabia (2010-11) and Algeria (2011).

Years before the prolonged oil-price crash that has spurred recent reform efforts in Saudi Arabia, the majority seemed content with their material lot in life – around 28.7% reported trouble making ends meet. This compares well with Algeria, polled in the early months of the Arab Spring, where nearly half of all respondents said that family income did not meet their needs.

For better or for worse, some kind of “rentier bargain” appears to hold for Saudi Arabia in 2010 as well. Gauging public support for authoritarian regimes can be a tricky subject while even under the most functional democracy it wouldn’t be surprising if citizens’ economic circumstances affect their stated views on their governments.

Still, survey questions about whether “Citizens must support the government’s decisions even if they disagree with them” allows us to try and address this – regardless of how people view a particular government. We shouldn’t expect economic circumstances to condition their overall deference to government.

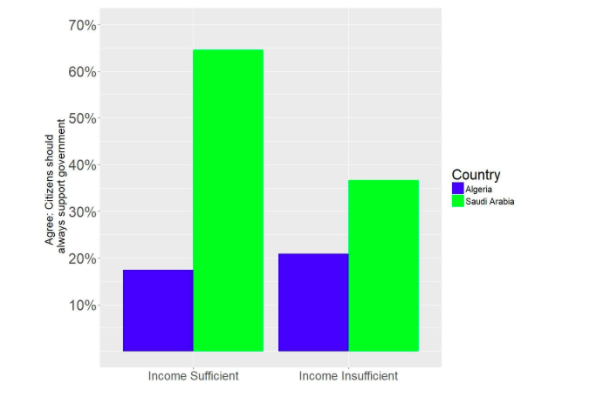

Figure 2: Respondent views on whether citizens should always defer to the government for Saudi Arabia (2010-11) and Algeria (2011), according to whether they viewed family income as sufficient or insufficient.

Yet this is the case. Around 65% of those whose family income fully covers their expenses were likely to defer to the government’s judgment, while only 36% of those unhappy with their economic situation were willing to do the same. Curiously, there is no such relationship in Algeria – possibly due to the collapse of Algerian welfare and subsidy programs in the late 1980s under the strain of the last oil price crash.

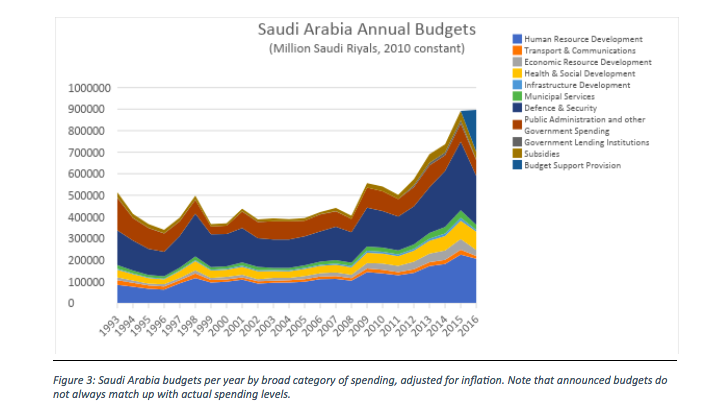

This snapshot of Saudi Arabian public opinion was largely taken just before the Arab Spring uprisings of 2011-12 – just before the Kingdom and other Gulf governments dramatically ramped up government spending as part of efforts (along with various crackdowns on demonstrations) to try and quell discontent (see Figure 3). In June of 2014, the IMF was already warning the Kingdom that high levels of spending might erode “fiscal buffers” needed to buy time in the event of a sudden drop in oil prices – such as the drop that immediately followed the IMF’s pronouncement.

Figure 3: Saudi Arabia budgets per year by broad category of spending, adjusted for inflation. Note that announced budgets do not always match up with actual spending levels.

All of which sets up the policy dilemma the Saudi Arabian government has been trying to negotiate for the past few years – striving to maintain deference without triggering discontent as government jobs dry up and subsidies are slashed. In part 2 of this article, we will examine the challenges facing Saudi Arabia – where no representative government exists beyond minor municipal bodies and a handpicked Advisory Council – in designing and implementing economic and social reforms sufficient to plug a hole in vulnerable government finances while dulling citizen expectations about future government largesse.