UPHOLDING THE CONSTITUTION AND PROTECTING CIVIL LIBERTIES DURING THE DARKEST OF TIMES IN AMERICAN HISTORY

Lessons learned from the Japanese American internment during World War II are more relevant than ever. In a recent opinion-editorial in the New York Times, Karen Korematsu, Fred Korematsu’s daughter, and Executive Director of the Fred T. Korematsu Institute, compared President’s Trump’s executive order temporarily banning travel from seven majority Muslim countries to the executive orders signed by President Roosevelt calling for the internment, “Executive orders that go after specific groups under the guise of protecting the American people are not only unconstitutional, but morally wrong.”[1]

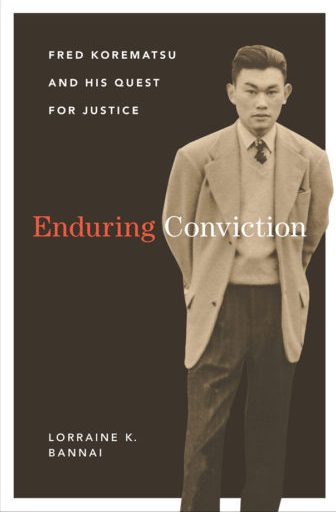

In this review, I consider a recent historical contribution to the study of the Japanese American internment during World War II, Lorraine Bannai’s Enduring Conviction: Fred Korematsu and his Quest for Justice. The book chronicles Fred Korematsu’s experience before, during, and after his more than two-and-half-year internment and his journey to the Supreme Court and beyond. Bannai is law professor and Director of the Fred T. Korematsu Center for Law and Equality at Seattle University School of Law, and was co-lead counsel in Mr. Korematsu’s coram nobis litigation in 1984. Enduring Conviction provides a deeper understanding of this mass trampling of civil liberties than the brief capsule summaries found in history text books and cursory citations in constitutional law casebooks.

Book cover for Lorraine K. Bannai’s “Enduring Conviction: Fred Korematsu and His Quest for Justice.” Korematsu, hands behind his back, in a tan blazer and dark slacks.

I.

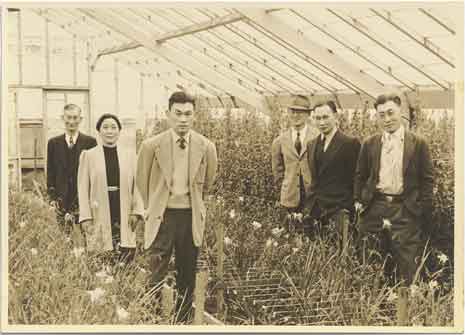

Fred Korematsu, a courageous twenty-two year-old man facing great prejudice, refused to comply with racist military orders that led to the forcible incarceration of over 110,000 Japanese and Japanese Americans by the U.S. government. Born in America, Mr. Korematsu was fully immersed in American mainstream culture. His life was typical of many well-rounded and assimilated Japanese Americans at the time, who did not speak Japanese and have never been to Japan. At Oakland High School, Mr. Korematsu swam, ran track, and played basketball and football.

Bonnai discusses the tremendous hysteria in America after the Pearl Harbor attack on the morning of December 7, 1941, which everything changed for Mr. Korematsu, his family, and other Japanese and Japanese Americans on the West Coast. Concerned with further Japanese threats, the FBI and Justice Department canvassed Japanese population centers on the West Coast arresting and detaining Japanese, German, and Italian enemy aliens whose names appeared on preexisting alien lists. These investigations were not enough for an America still angry about Pearl Harbor. Soon politics and public opinion played hand-in-hand to support the internment.

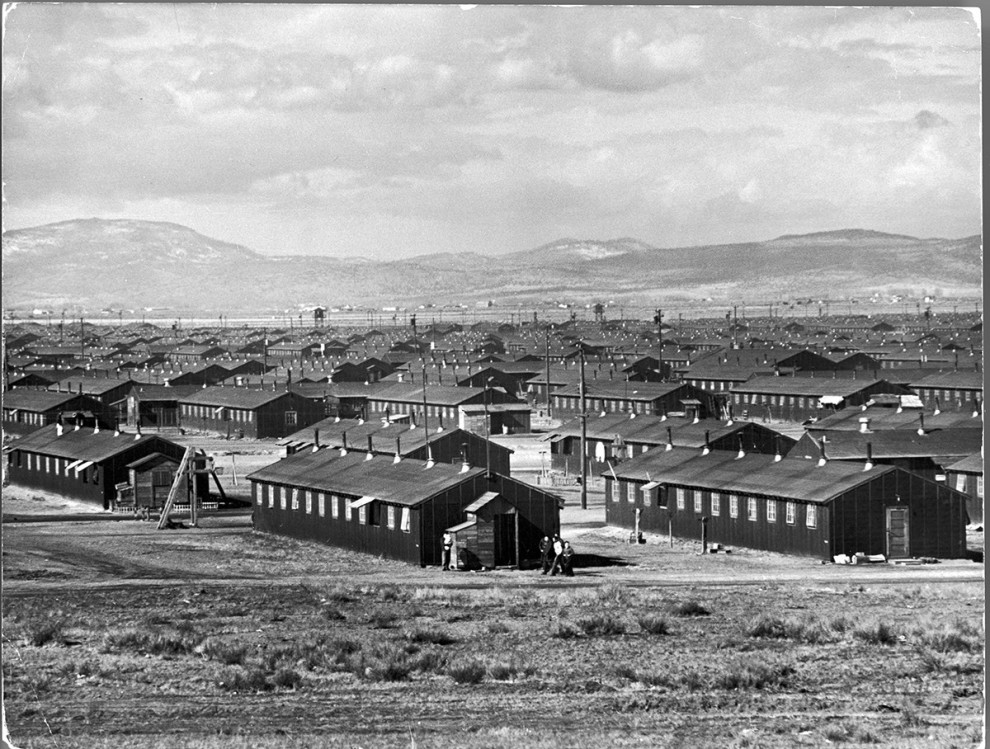

In great detail, Bonnai describes the military efforts to remove the Japanese and the 108 Civilian Exclusion Orders leading up to the internment. Lt. General John L. DeWitt, head of Western Command, who held racist views, believed that Japanese Americans were treacherous and were a national security risk, and their removal from the West Coast was necessary. Though DeWitt lacked any concrete evidence to support his position, he made a final recommendation in favor of mass evacuation. The internment’s design allowed for plausible deniability by President Roosevelt and Congress—there was no direct authorization of the internment of an entire racial group. Instead, military officers like DeWitt only issued “curfew orders” and “detention orders” based on “military necessity” directly aimed at the Japanese.

Approximately 120,000 individuals of Japanese ancestry were considered disloyal. About 80,000 of these people held indefinitely were U.S. citizens. In the absence of even a single case of espionage on the west coast during World War II, or any declaration of martial law, Japanese men, women, the elderly, and children, were indefinitely detained, without being provided any due process.

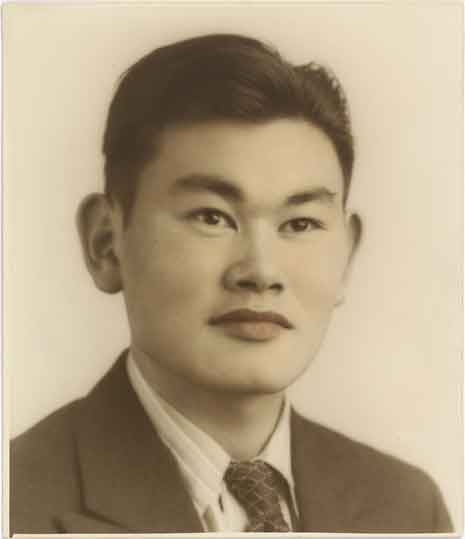

A young Fred Korematsu, in profile, 1940

Mr. Korematsu felt alone in doing what he felt was right because there was little community support for his position. In fact, many Japanese Americans were resentful of Mr. Korematsu for speaking up and taking a stand. At the time the Japanese American Citizens League urged the Japanese American community to avoid making waves, and encouraged them to comply and cooperate with the military. Mr. Korematsu eventually got help. Believing he found an ideal test case to challenge the removal order, Ernest Besig, Director of the San Francisco chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union, met with Mr. Korematsu, and then Attorney Wayne Collins was recruited to handle the defense. Collins challenged the authority of the President, Congress, and the military by claiming that the executive order, the exclusion order, and public law deprived Mr. Korematsu of his constitutional right to due process and equal protection.

Mr. Korematsu waived a jury trial. During his bench trial before Judge Aldolphus St. Sure, F.B.I. Special Agent Oliver Mansfield testified about interviewing Fred, and produced Fred’s statement admitting his Japanese ancestry and being aware of his defiance of the exclusion order. While Mr. Korematsu testified about lacking any connection to Japan, and being a loyal American citizen. On December 31, 1942, Judge St. Sure ruled Mr. Korematsu guilty and sentenced him to five years probation to be served in military custody. Mr. Korematsu appealed all the way to the Supreme Court.

Korematsu Institute – A photo of a newspaper article that reads “Japanese American’s Fight for Justice,” with an image of Korematsu

II.

The thrust of Enduring Conviction is found in Chapter Eight, entitled, “The Ugly Abyss of Racism” where Bonnai analyzes the other internment cases which also reached the Court: Yasui v.United States[2], Hirabayashi v. United States[3], and Ex Parte Endo[4] to expose the manner in which the government and the Court worked together to address the separate curfew and exclusion orders, but actively avoided the real issue: is it constitutional to intern an entire racial group based on their ancestry? In each instance, the Court was reluctant to second-guess military judgment, and more inclined to offer complete deference to the government to detain Japanese Americans.

After years of delay, on December 18, 1944, the Court in Korematsu restricted its holding to the question of the evacuation alone, avoiding the issue of the internment’s constitutionality.[5] In upholding the exclusion order, Justice Black, writing for the majority, assured that the case was not about racial prejudice; it was about an exclusion order. “Korematsu was not excluded from the military area because of hostility to him or his race. He was excluded because we are at war with the Japanese Empire.” The majority announced that it would not reject the judgment of the military and Congress that disloyal citizens were amongst the population and that it was impossible for military authorities to immediately segregate the disloyal Japanese Americans from the loyal.

The majority opinion was met with backlash in the form of fierce dissents which effectively obliterated the majority’s reasoning. First, Justice Murphy claimed that the entire internment was a “legalization of racism.” In his view, the case was motivated by racial prejudice, which facilitated an erroneous blanket racial assumption—all Japanese born inside or outside of the U.S. were disloyal. Second, Roberts’s argued “To focus solely on the validity of the exclusion orders is to shut our eyes to reality.” He criticized the majority for dividing the race issue from the exclusion order, which he believed to be indivisible. Third, Justice Jackson declared a double standard existed: had Fred been German or Italian alien enemy, he would not have been found violative of the order. Aware of the dangerousness precedent Korematsu would set, and its potential to be a “loaded weapon” for the Executive Branch, Jackson warned that once a judicial opinion rationalizes that a military order conforms to the Constitution or that the Constitution sanctions the order, “the court for all time has validated the principle of racial discrimination on criminal procedure and of transplanting American citizens.”

Carl Mydans/Getty Images – Barracks at an internment camp in Tule Lake, CA

III.

The last three chapters discussing the coram nobis litigation are especially insightful. A fortuitous finding by Professor Peter Irons in September 1981 became the genesis for appealing the convictions in Korematsu in the coram nobis litigation.[6] Acting under a Freedom of Information Act request for Department of Justice documents, Irons combed through previously misfiled evidence showing that the War Department’s report about the internment was false, and uncovered an apparent government cover-up. Irons learned that the documents, which were never disclosed to the Court, revealed that the government suppressed and altered evidence undermining their military necessity claim.

With the help of committed Japanese Americans attorney who worked pro bono, on January 31, 1983, Fred’s petition for writ of coram nobis was filed in the Northern District of California asking the court to overturn his criminal conviction because government attorneys withheld available information which negatively impacted the court’s ruling. At the final hearing, Judge Marilyn Patel determined that the government relied on baseless misrepresentations and the racist views of the military commanders. Based on those findings, Patel granted a writ of coram nobis and dismissed Fred’s indictment. Unfortunately, this was only a partial victory because as Patel explained, her ruling did nothing to affect the Court decision which remains law.[7]

Enduring Conviction shows how politics and racial prejudice can conspire to trample the civil liberties of an entire racial group during a time of war, based on fabricated claims of military necessary. While beyond the scope of this review, strong parallels exist between the internment of Japanese immigrants and Japanese Americans and the post-September 11th (“9/11”) “war on terror.” Mindful of this, in the epilogue, Bonnai refers to the dangers for the 2012 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) which authorizes the indefinite detention of U.S. citizens who the U.S. government deems them to be associated with, or supported, terrorists or terrorist activities. These concerns about U.S. citizens being held indefinitely, without being provided any due process are real. What happens if there is a series of large-scale terrorist incidents, close in time, in the United States? Amidst the immediate shock, anger, fear, and outcry, would President Trump sign executive orders authorizing the curfew and exclusion of individuals or groups under suspicion based on the NDAA? In the final analysis, Bonnai’s volume is a worthwhile read for those interested in leaning about some of the worst events and court rulings in American history, and serves as a reminder that the constitutional rights of American citizens should always be safeguarded during times of war, and in the darkest of times in American history.

Justin Sullivan/Getty Images – A monument honoring the dead stands at Manzanar National Historic Site

[1] Korematsu, Karen. 2017. When lies overruled rights. New York Times, February 18.

[2] Yasui v. United States, 1943, 320 U.S. 115.

[3] Hirabyashi v. United States, 1943. 320 U.,S. 81.

[4] Ex Parte Endo, 1944. 323 U.S. 283.

[5] Korematsu v. United States, 1944. 323 U.S. 214.

[6] Irons, Peter. 1983. Justice at War: The Story of the Japanese American Internment Case.

[7] Korematsu v. United States, 1984. 584 F. Supp. 1406, 1420.