BY CASEY SCHUTTE

The law does not trust them to vote. It forbids them from watching certain movies in the theater or signing up for a credit card on their own. Consuming alcohol is certainly off limits, as is smoking cigarettes. Society proscribes certain activities for these people because, the thinking goes, they lack the wisdom of age and so cannot be trusted to make informed choices.

But when some children commit crimes, the calculus changes. Suddenly the legal system has no problem assigning children responsibility for their own decisions, implicitly concluding that crime committed by the young is the product of a deliberate decision-making process. These children are sentenced to die in prison.

And it is not only sixteen- and seventeen-year-olds, adolescents who may look old enough to buy alcohol, who are sentenced to life without parole. The Equal Justice Initiative has documented seventy-three cases in the United States where children thirteen- and fourteen-years-old have been given a sentence of life without parole (LWOP) (Equal Justice Initiative 2007). Absent a change in their sentence or some form of pardon, these kids will never again experience life outside an institution. All seventy-three of them are people of color, and most have histories as victims of abuse or neglect.

Take, for example, Quantel Lotts. Quantel grew up in a troubled section of St. Louis. His mother sold and used drugs at home, and Quantel lived in three different foster homes before his father took him to live in a different part of the state. During an argument with his stepbrother, Michael, Quantel fatally stabbed him with a knife. Quantel, fourteen at the time of the stabbing, was sentenced to LWOP.

Even the combination of young age and mental disability does not preclude a sentence of life without parole. Joe Sullivan has a severe cognitive impairment and was thirteen when an older codefendant accused Joe of a sexual battery that allegedly took place in a home they burglarized together. Joe denied the allegations and still maintains his innocence. He was sentenced to die in jail and is currently serving his time in Florida.

The United States stands alone in its willingness to hand out LWOP sentences to children. A 2005 Amnesty International/Human Rights Watch study found that while at least twelve countries still had laws allowing juvenile life without parole, only three other countries had children actually serving the sentence: Israel had seven, South Africa four, and Tanzania one. At this point, the United States is likely the only country in the world that continues to impose the sentence in new cases.

The United States’ status as an outlier is due in part to the fact that juvenile LWOP contravenes several international treaties. The Convention on the Rights of the Child, for example, has been ratified by 193 nations; the United States is one of only two countries in the world that has refused ratification. Article 37 of the Convention states, “Neither capital punishment nor life imprisonment without possibility of release shall be imposed for offences committed by persons below eighteen years of age” (Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights 1989).

Such juvenile sentences also constitute a violation of additional international treaties including: the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights; the United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Administration of Juvenile Justice; the United Nations Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment; and the American Declaration of the Rights and Duties of Man (American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 2009).

In 2010, the Supreme Court brought the United States closer to international norms when it placed substantial limitations on states’ freedom to sentence juveniles to life without parole: no LWOP for non-homicide crimes. The Supreme Court case Graham v. Florida involved a sixteen-year-old boy, Terrance Graham, who pled guilty to armed burglary with assault and battery and attempted armed robbery. Six months later, he was arrested for a home invasion robbery in violation of his plea agreement and sentenced to life without parole. Graham challenged that sentence as violating the Eighth Amendment ban on cruel and unusual punishment, and the court agreed. In the majority opinion, Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote: “The judgment of the world’s nations that a particular sentencing practice is inconsistent with basic principles of decency demonstrates that the court’s rationale has respected reasoning to support it.”

And it appears that the matter is still not settled. As of the time of this writing, the Supreme Court was set to hear oral arguments in March 2012 in two cases challenging juvenile life without parole in murder cases. The two cases, Miller v. Alabama and Jackson v. Hobbs, both involve youths who were fourteen-years-old at the time of their crimes. The juveniles’ petitions to the court argued that there is a “national consensus” against a sentence of life without parole for children as young as fourteen.

The Supreme Court’s shift on the acceptability of juvenile life without parole comes at least in part from an emerging body of scientific knowledge about how the adolescent brain operates. Though this knowledge may often come from research conducted in artificial settings and may not translate perfectly to emotionally charged real-life moments, it still provides insight into how adolescents think and act differently from adults.

One of the most important research findings is that even though intellectual maturity reaches adult levels at age sixteen, psychosocial development continues into early adulthood. This can change our perception of adolescent culpability for a crime; yes, an adolescent may have the same ability to reason as an adult, but real-world decisions involve a lot more than a simple question of intellect or rational judgment. In high-pressure situations where a crime is being committed, adolescents must contend with their shortsightedness, impulsivity, and susceptibility to peer influence. And in these areas, as research by the Macarthur Foundation Research Network on Adolescent Development & Juvenile Justice (n.d.) has demonstrated, adolescents differ significantly from adults.

The network conducted studies to assess how adolescents and adults envision themselves in the future and found that adults look much further ahead and therefore display a stronger orientation toward the future. Generally, adolescents are far less likely to consider future consequences of their actions. In one study, the network gave subjects the choice between smaller, immediate rewards or larger, longer-term rewards. Adolescents consistently had a lower threshold than adults for giving in to the smaller, more immediate reward. This tendency to focus on immediate rewards and ignore long-term consequences has obvious implications for criminal conduct; where an adult might judge the possibility of punishment as outweighing the payoff for a crime, an adolescent is more likely to think only of the short-term reward.

The organization’s research also showed that adolescents have poor impulse control and that individuals are less likely to seek thrills and act impulsively as they age. To examine this, researchers gave study subjects a “Tower of London” task, where the goal was to solve a puzzle. When subjects made a wrong move, it took extra moves to undo it. The research showed that adolescents took less time than adults to plan and consider their first move, preferring instead to dive right in to the task, often with predictably negative consequences. This lack of sensitivity to risk, combined with an increased sensitivity to rewards, makes juveniles more likely to take risks in pursuit of immediate benefit. In crime situations, this impulsivity can have dangerous and disastrous consequences.

Finally, the network looked at vulnerability to peer pressure and came up with probably the least surprising of its research findings: youths are more susceptible to peer influences than adults. One study involved a computer car-driving task and showed that the mere presence of friends increased risk taking for youth and college undergraduates, but the same was not true for adults. Overall, youths’ desire for peer approval and fear of rejection often leads them to take actions they would otherwise refuse.

Collectively, these research findings demonstrate that adolescent crimes may be more the product of age and immaturity than enduring lawlessness. This raises important questions about the wisdom of locking children up for life: does a child who commits a crime at fourteen deserve to be incarcerated forever, when the developmental circumstances that helped incite the criminal behavior will fade with age?

Sentencing juveniles to die in prison is bad policy and should be banned. The Supreme Court has the opportunity to do just that when it decides Miller v. Alabama and Jackson v. Hobbs and should take the opportunity to issue a categorical rule outlawing the sentence. Absent such a decision, state legislatures should recognize the immoral nature of these sentences and end juvenile life without parole within their borders, as at least six states have already done. Advocacy groups have an important role to play in this state-level process and can work to educate legislators about the numerous reasons juveniles should not receive life sentences.

Whether the change comes from a judicial decision or from legislation, it is time to stop sentencing America’s children to die in prison.

References

American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009. Life without parole for juvenile offenders.

Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch. 2005. The rest of their lives: Life without parole for child offenders in the United States.

Equal Justice Initiative. 2007. Cruel and unusual: Sentencing 13- and 14-year-old children to die in prison. Montgomery, Alabama: Equal Justice Initiative.

MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Adolescent Development & Juvenile Justice. n.d. Issue Brief 3.

Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. 1989. Convention on the Rights of the Child. Adopted and opened for signature, ratification and accession by General Assembly resolution 44/25 of 20 November 1989. Entry into force 2 September 1990, in accordance with article 49.

This article was originally published in the 2012 edition of the Kennedy School Review.

Casey Schutte is a concurrent degree student, pursuing a law degree from the University of California, Berkeley, and a Master in Public Policy from the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University. He has a master of social work degree and previously worked in child welfare in Wisconsin.

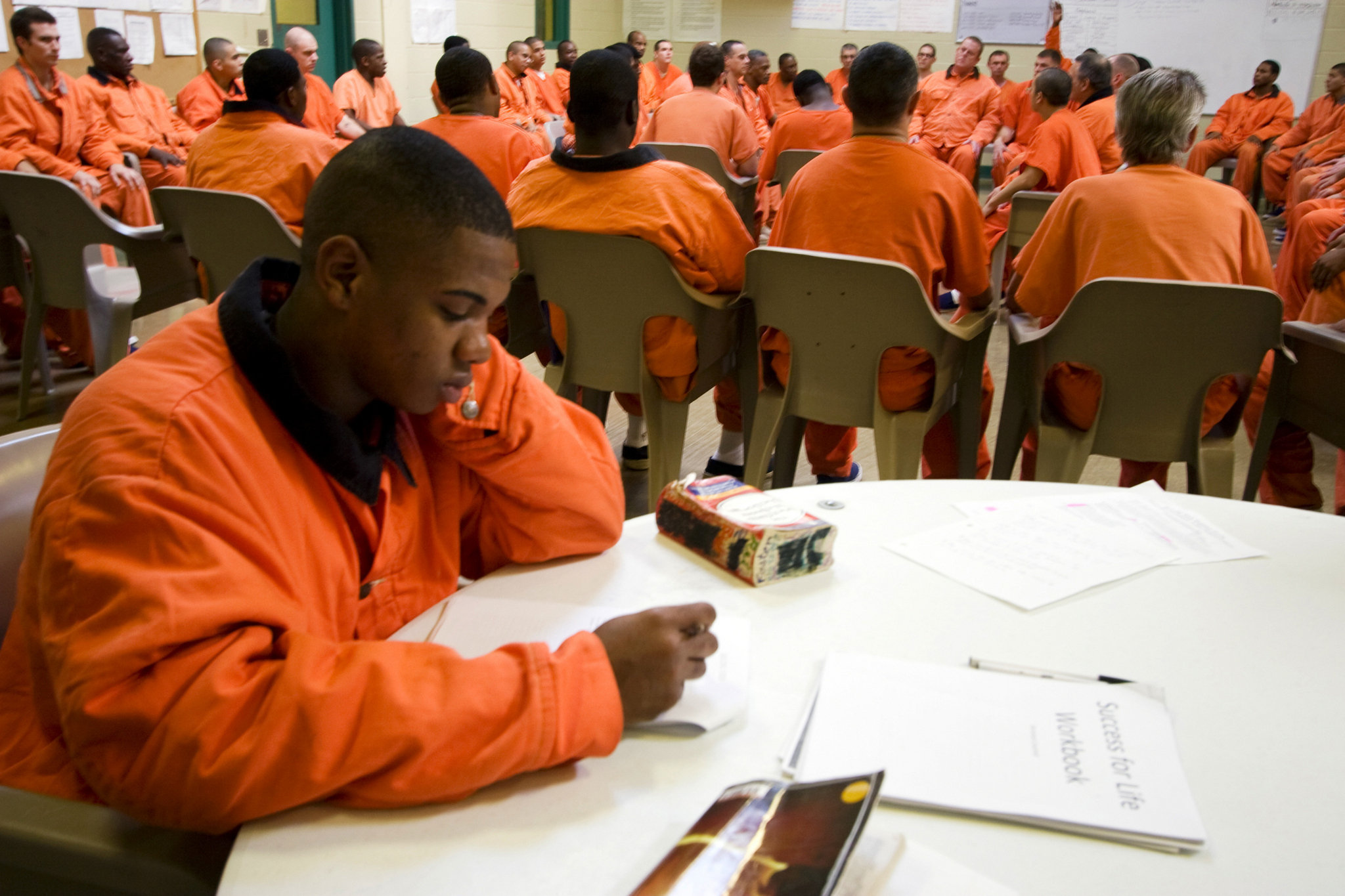

Photo source here.