Argentina has a long tradition of women mobilizing for their own rights, human rights, and justice in their country. The 30-year-old struggle for abortion rights in Argentina was paved by local women’s organizations and by a constant persistence in guaranteeing women’s right to choose. Getting there was not a coincidence nor just luck. It took years of planning, itineration, and an ideal political scenario to make it happen. There is no wonder many movements in Latin American countries, like Colombia and Mexico, have followed Argentina’s steps towards mobilizing for the right to choose and against violence towards women.

Using Popovic’s framework of waging strategic nonviolent resistance, this article will explain the strategies and principles of success that Argentinian women used to achieve the right to choose in their country. First, this paper will provide context and a brief history of the larger feminist Argentinian movement. Next, it will explore the specific objectives of the National Campaign for Legal, Safe, and Free Abortion as part of the Green Wave movement. To further help understand these mobilizations, the paper will explain the theory of waging strategic nonviolent resistance with unity, planning, and nonviolent discipline. In closing, the paper discusses analysis with some key remarks about abortion right movements and the importance of timing.

History of the Argentinian Feminist Movement

Women’s activism in Argentina grew stronger after the dictatorship and genocide of the late 1970’s. The military regime engaged in widespread human rights abuses, including the kidnapping, torture, and murder of tens of thousands of people, primarily leftist militants, trade unionists, and other perceived regime opponents. Many of these people “disappeared,” meaning they were taken into custody and never seen again.[i]

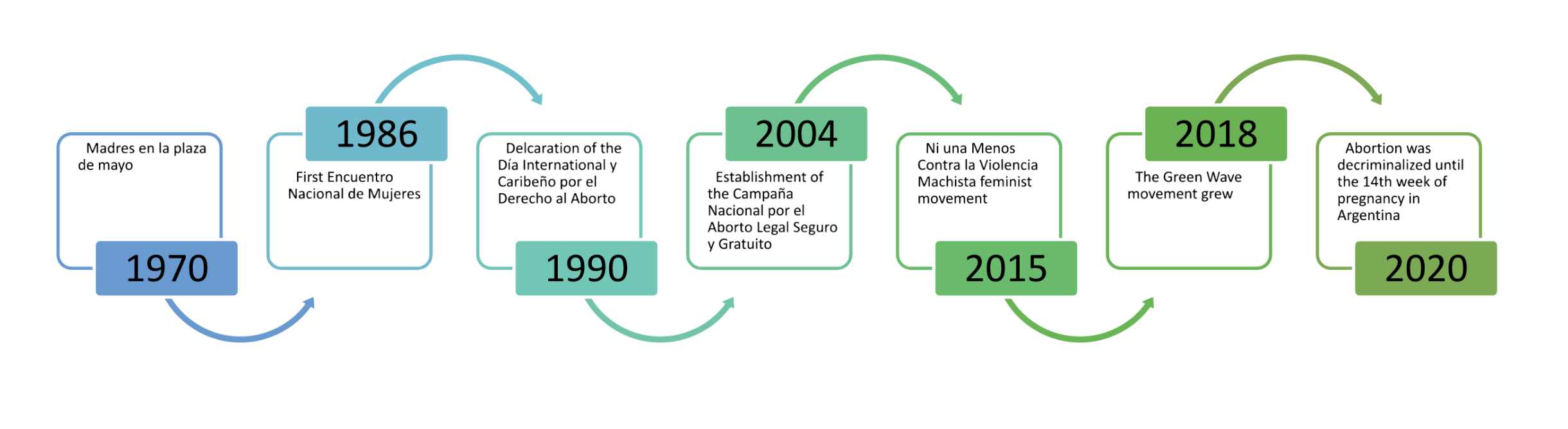

The Madres de la Plaza de Mayo formed in response, as mothers massively mobilized for their disappeared sons at the hands of the dictatorship. The movement’s symbol was a white handkerchief placed on the head, made initially from their son’s childhood blankets. The white cloth differentiated this movement from any other pilgrimages in the country.[ii] Inspired by the Madres de la Plaza de Mayo, the first Encuentro Nacional de Mujeres (ENM, National Women’s Meeting) was held in 1986 that gathered women from organizations, parties, traditions, and unions.[iii] The ENM gatherings gained inspiration from previous women’s movements in the country and were held in various regions of Argentina to create a place where women’s claims had a space to be heard. In the first ENM, abortion was not on the agenda. ENM discussions about abortion were set in parallel debates in the procedure of informal discussions.[iv] In 1990, a sub-committee on abortion rights declared September 28th as the Día Latinoamericano y Caribeño por el Derecho al Aborto (Latin America and Caribbean Day for the Decriminalization and Legalization of Abortion). But it was only in 1997 that abortion officially became part of the ENM program.[v]

In the post-dictatorship period, the political climate in Argentina was still uncertain and unstable, with different governments and political parties in power, which made it difficult for civil society organizations to establish themselves and advocate for specific issues. However, 2001 the Aborto como Derecho (Abortion as a Human Right) committee was formed “as an assembly of women’s fractions from all leftist political organizations.”[vi] The topic of abortion was and remains a highly controversial and sensitive one, with deep moral, religious and cultural roots. It took time for society to be ready to start this conversation and for a larger movement to develop. It was not until 2004 when the Campaña Nacional por el Aborto Legal Seguro y Gratuito (National Campaign for Legal, Safe, and Free Abortion – referred to as the “Campaign”) was officially established and leaders of the coalition for abortion rights in Argentina were recognized. The Campaign slogan stated: Educación sexual para decidir, Anticonceptivos para no abortar y Aborto legal para no morir (Sexual Education to decide, contraceptives to prevent abortions, and legal abortion to prevent deaths).[vii]

In 2015, the Argentinian feminist movement continued to organize including bringing together thousands of women under the Ni Una Menos contra la Violencia Machista (Women Against Male Violence) statement. The cause of violence against women mobilized Argentinian women to the streets, making a public call that their lives mattered.[viii] This mobilization was necessary for the abortion rights agenda to gain even more importance in Argentina. It created momentum and an ambiance in the streets where women’s voices were heard. From there on, mobilizations for women’s rights became periodic in Argentina, and the streets became a stage for their revindication of rights.

As for legislation, since 2005, more than nine bills have been presented in Congress to decriminalize abortion in Argentina. From 2005 to 2018 there was an increase in mobilizations to decriminalize abortion because of the efforts of feminist and human rights organizations. The feminist movements provided platforms for individuals and groups to share information and mobilize around the issue. Social media also helped to amplify the voices of those who support the legalization of abortion, and to create a sense of momentum and urgency around the issue. In 2018, for the first time a bill was voted positively in the House, but unfortunately rejected in the Senate[ix].

By this year, the Ni Una Menos movement grew into La Marea Verde (The Green Wave) movement. A wave of women with green handkerchiefs occupied the streets, calling for their right to choose. The Green Wave was alive and growing. Finally, on December 20th, 2020, the Argentinian Congress approved the decriminalization of abortion until the 14th week of pregnancy.

The Green Wave’s Objectives

The Green Wave movement towards abortion rights did not rise randomly, nor was it only a reaction to a special event. The Green Wave is a social and political movement that emerged in Argentina during 2018, which works for the legalization of abortion and fights for women’s rights while promoting gender equality. The movement is composed of various organizations, including feminist, human rights, sexual and reproductive health groups, and other entities that share similar goals and values. One of the leading organizations includes the Campaña Legal por el Aborto Legal Seguro y Gratuito (The Campaign), who are considered one of the main actors in the pro-choice movement in the country and gathered more than 305 other organizations to the cause.[x]

Specifically, the Green Wave movement mobilized so that women, trans-men, and non-binary people could have: i) safe health services, meaning access to a health facility and quality service; ii) free access to abortions, meaning being able to easily find a way to obtain an abortion without depending on economic means; and iii) the decision to have an abortion be freely made, meaning each person has choice over their own body without the intervention of third parties (for example, medical approval). Moreover, as stated by Sutton, the Green Wave goals were based on “[t]he right to bodily self-determination and integrity are embedded in a long lineage of social and legal change efforts, from slavery abolition to women’s liberation, LGBTQ rights, ending torture, and securing human rights (Petchesky 2005; Kreimer 2007; Herring and Wall 2017).” [xi] The Green Wave is known for leading massive national marches and mobilization to achieve the legalization of abortion in Argentina.

Waging Strategic Non-violence Resistance in Argentina- Campaña Nacional por el Aborto Legal Seguro y Gratuito

According to Ackerman and Popovic[xii], the three principles of success in waging strategic nonviolence are the unity of the group, planning, and nonviolent discipline. These principles are demonstrated throughout the road to abortion rights in Argentina.

Unity of the Campaign

The Campaign complies with the three vital requirements, as stated by Popovic, to have the unity of the people, unity within the organization, and unity of purpose.

The unity of the people is witnessed through the mass mobilization of the movement and its diversity. Both are clear signs of the strength and harmony that surrounded this movement as the Campaign was composed of feminist groups and women’s organizations across Argentina. The Campaign had the support of 700[xiii] groups and different personalities linked to human rights organizations, academic and scientific fields, health workers, trade unions, and various social and cultural movements, including peasant and education networks, organizations of unemployed people, recovered factories, student groups, and social communicators, among others.

Since the early days of the Campaign, inclusion was on the agenda. But this did not mean that groups were effortlessly named and recognized inside the movement. Multiple debates were held within the Campaign until the inclusion of trans-men and non-binary communities was agreed upon, arguing that “broadening abortion activism to include different bodies and identities was in the interest of both the trans and feminist movements.”[xiv] When Congress discussed an abortion rights bill in 2018, it held broad hearings open to the Campaign and citizens, and among those who participated in included representation from the trans community. Additionally, the presence of trans and non-binary persons in the massive rallies was vital in identifying the Campaign as a diverse movement.[xv]

Unity within the organization and unity of purpose of the Campaign leadership was visible across the country with their presence in all federal states of Argentina. The Campaign message was broad and consistent, with tools such as social media and symbols like the green handkerchief, it was clear unity was visible nationwide.

Strategies for the Right to Choose

The Argentinian movement towards decriminalizing abortion used a myriad of strategies for achieving their goal. From gatherings among organizations, civil society, politicians, academics, and historical organizations, to institutional lobbying in Congress, media interviews, organizing events, and juntanzas (feminist gatherings). In addition to these strategies, the embodiment of a symbol and using social media helped create the institutional opportunity for the right to choose in Argentina to become a reality. The Campaign was deliberated, detailed, and planned, complying to Popovic’s second wagging strategy: strategic sequencing and tactical capacity building.

The Capacity of The Campaign

Tactical capacity building includes to “build up their capacity to recruit and train activists, gather material resources, and maintain a communications network and independent outlets for information.”[xvi] Still present today in all federal states of Argentina, the Campaign was founded from a strong feminist organization led by influential Argentine women and born in a top-down manner. However, over the years, it expanded by adjusting its discourse of the right to choose, growing immensely within the country, and reaching all levels of society. For example, youth voices were included by creating youth groups within the organization and these became a new part of the Campaign. Additionally, the use of social media allowed young people to engage with the movement and mobilize. Youth inclusion took the discussion of abortion rights to schools, leading to the conversation about abortion reaching even the most conservative’s households. [xvii] Women intentionally planned and with the Campaign including youth, it inevitably brought the conversation about the right to choose to many areas of Argentinian society.

“In the debate on the legalization of abortion, I learned that struggles are not only won by marching in the street but also by talking to family, friends, and schoolmates. You’re not always going to find people who agree with you.”[xviii]

-Justina De Pierris, 15 years old, student

The Campaign implemented what Gene Sharp[xix] calls: methods of communication for a wider audience using symbols and social media.[xx] The establishment of the symbols and the use of social media were vital for the Campaign’s success. The green handkerchief was Argentina’s leading symbol of the Campaign and pro-choice movement. In 2018, thousands of women nationally started to wear green handkerchiefs in their everyday lives.[xxi] It became a symbol of feminism and a symbol of choice, hope, and life. Paula Maffía, a 35-year-old singer from Argentina, stated that “There is a before and an after the debate on the legalization of abortion in Argentina. We do not take the green handkerchief out of our backpacks or our wallets because we believe that this struggle is not temporary.”[xxii] The symbolism of the green handkerchief was maximized by the assembly of bodies and the massiveness of the movement as it created a wave of women towards the same goal—decriminalization of abortion, in law and society. [xxiii]

Furthermore, social media had a key role in tactical capacity since it enhanced the methods of communication and maintained interaction between federal states in Argentina. The Campaign created official social media accounts on platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube, to share information, news, and updates about mobilization efforts.[xxiv] Every person with a social media account could replicate messages, increasing the reach of the Campaign to as many people as possible. Live streaming was used to broadcast events, marches, and rallies in real-time, allowing people who could not be physically present to participate and feel connected to the movement. Urgent calls for action could be spread through social media such as in 2020, the hashtags #EsUrgente (#ItisUrgent) and #AbortoLegal2020 (#LegalAbortion2020) were virilized and used to pressure President Fernandez to send the abortion bill to Congress in November.[xxv]

Strategic Sequencing and Lobbying in Congress

Strategic sequencing is the process of strategically planning and executing a sequence of nonviolent actions to achieve a specific political goal.[xxvi] Strategic sequencing could be easily observed by the Campaign’s building and development in Congress. Early on, even before the Campaign was established, the feminist movement understood that the only way abortion could be decriminalized was through modifying the law.[xxvii] The Campaign in 2005 created strong relationships with pro-choice legislators, which led to the opening of discussion about abortion rights in legislative committees.[xxviii] In the same year, 100,000 signatures were collected by the Campaign to present a petition to Congress on decriminalizing abortion. This was a sign for future success since, as stated by Chenoweth, large campaigns are more likely to succeed than small campaigns.[xxix] Having the support of 100,000 signatures was also a message to legislators that abortion could no longer be set at the end of the agenda, but instead, was crucial in the Argentinian national debate. The 100,000 signatures provided the Campaign with legitimacy and power.

The Campaign power was further advanced through the creation of a lobbying commission in 2013, which kept the decriminalization of abortion on the agenda. Besides the pro-choice legislators, different parties came together to have conversations with legislators that disagreed with the bill. In 2018, the Campaign gathered relevant public opinion variables that explained the opposition to the legislation in Congress and found that “religiosity, right-wing ideology, and people who live in the north-west, north-east and center-west regions of the country (Reynoso, 2021)” were their prominent opponents.[xxx] Additionally, the issue of conscientious objection to private clinics and doctors was a complex topic for the bill’s approval. The Campaign worked from 2018 to 2020 with the pro-choice legislators to address these issues and created popular support and political approval for the 2020 bill.

Nonviolent Mobilization

Popovic’s third principle for effective strategic nonviolence resistance is a nonviolent discipline that includes widespread participation and delegitimizing the oppressor.[xxxi] The Argentinian pro-choice movement did not face physical repression from the government during the actions of the Campaign, nor repression from the police forces. However, the Campaign’s actions were a response to years of silent repression implemented by the government and the state system by refusing to recognize women’s rights and their ability to choose over their own bodies. A repressive legislation did not recognize bodily autonomy and maintained a health system without women’s reproductive health. The widespread participation of the movement was critical to the Campaign’s success, and it did not become present until 2015 after the Ni Una Menos mobilizations, where a discipline of getting on the streets and calling for women’s rights became recurrent every year.[xxxii] The rallies from 2018 to 2020 that determined the Green Wave allowed women to “embraced feminist beliefs more openly and developed creative repertoires of action, including street performative events (Sutton and Vacarezza, 2020).”[xxxiii] These massive mobilizations allowed the Campaign to occupy spaces and encouraged a widespread conversation around the decriminalization of abortion. This de-stigmatization of abortion was created by the activists’ presence in the streets through dancing, singing, displaying shimmering bodies, and carrying their green handkerchiefs every time and everywhere.[xxxiv]

Delegitimizing the oppressor in the feminist movement looks very different in Argentina. The movement pressured the oppressor by rallying support for specific rights and using the movement’s political power to encourage the decriminalization of abortion in Congress. The oppressor came in different shapes and forms, or finally in this case the eventual supporter, but the most important and influential was the President Alberto Fernandez, who had the power to encourage support for the bill to win a favorable outcome. In 2020, the massive mobilization and the Campaign’s strength and political power in the country led President Alberto Fernandez to intervene in the legislative negotiations in Congress.[xxxv] It was a political opportunity that the Campaign did not lose by demanding what President Fernandez promised during his presidential election. Additionally, since 2018, the Campaign gathered support from international organizations such as Amnesty International, which gave them further leverage to pressure the government towards their cause.

Argentina’s Influence in Latin-America

Popovic’s framework of waging strategic nonviolent resistance explains how the unity of the movement, the strategic decisions made through capacity building, and the maintaining of the nonviolent discipline, Argentinian women, trans-men, and non-binary people gained their right to choose. This framework is helpful in the identification of these three categories of the nonviolent movement. However, further specification is needed in identifying strategies for movements that are not trying to overturn power but rather change something specific in the system, which this area is yet to be developed.

The Argentinian movement was full of symbols, manifestations, planning, and coordination. However, the approval of the right to choose also developed because of the movement’s influence across Argentina and a political opportunity that could not be missed. The change of government from President Macri to President Fernandez opened a window for the bill to decriminalize abortion to go first in the legislative agenda; Additionally using President Fernandez’s political power to obtain swing votes in Congress. The Campaign leaders took advantage of the situation and used the opportunity to activate its nationwide solid network, and their efforts paid off. This Campaign showed the importance of preparation, small efforts, extensive networks, and the power of occupying spaces to have messages heard.

The Campaign’s influence extended beyond national borders. Feminist movements throughout Latin America in Colombia, Mexico, Ecuador, and Panama among others, have appropriated the green handkerchief as a symbol for their own national movements for the right to choose. Likewise, regional meetings about abortion rights are held yearly, such as Reunión Latinoamericana y del Caribe “Causa Justa” (Latin American and Caribbean Meeting “Causa Justa”).[xxxvi] Today there is a robust Latin American network for abortion rights, conjunctively thinking about actions to improve and gain the right to choose in the region.

References:

[i] Farer, Tom. “I Cried for You, Argentina.” Corte Interamericana de Derechos Humanos. Corte Interamericana de Derechos Humanos, 2016. https://www.corteidh.or.cr/tablas/r31089.pdf.

[ii] Ackerman, Peter, and Jack. DuVall. A Force More Powerful: a Century of Nonviolent Conflict. Chapter 7. 1st ed. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2000.

[iii] Nuria Inés Giniger. “Abortion is law.” Kvinder, Køn & Forskning, vol. 33, no. 1, 2022. https://tidsskrift.dk/KKF/article/view/125645

[iv] Lopreite, Debora. “The Long Road to Abortion Rights in Argentina (1983–2020).” Bulletin of Latin American Research, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1111/blar.13350.

[v] Nuria Inés Giniger. “Abortion is law.” Kvinder, Køn & Forskning, vol. 33, no. 1, 2022. https://tidsskrift.dk/KKF/article/view/125645

[vi] Ibid.

[vii] Ibid.

[viii] Lopreite, Debora. “The Long Road to Abortion Rights in Argentina (1983–2020).” Bulletin of Latin American Research, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1111/blar.13350.

[ix] The Guardian. “Argentina Holds Historic Abortion Vote as 1M Women Rally to Demand Change.” The Guardian. Guardian News and Media, August 8, 2018. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2018/aug/07/argentina-abortion-vote-legalisation-senate-mass-rally.

[x] Anzorena, Claudia. La Campaña Nacional por el Derecho al Aborto Legal, Seguro y Gratuito: una experiencia de articulación en el reclamo por el ejercicio de la ciudadanía sexual y reproductiva. IX Jornadas de Sociología. Facultad de Ciencias Sociales, Universidad de Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires, 2011., 2011. https://www.aacademica.org/.

[xi] Sutton, Barbara. “Reclaiming the Body: Abortion Rights Activism in Argentina.” Feminist formations 33, no. 2 (2021): 25–51.

[xii] Srdja Popovic et al, A Guide to Effective Nonviolent Struggle, (Belgrade, Serbia: Centre for Applied Nonviolent Action and Strategies, 2007), pamphlet pgs. 84-93

[xiii] Sutton, Barbara. “Reclaiming the Body: Abortion Rights Activism in Argentina.” Feminist formations 33, no. 2 (2021): 25–51.

[xiv] Fernández Romero, Francisco. “‘We Can Conceive Another History’: Trans Activism Around Abortion Rights in Argentina.” International journal of transgender health 22, no. 1-2 (2021): 126–140.

[xv] Ibid.

[xvi] Srdja Popovic et al, A Guide to Effective Nonviolent Struggle, (Belgrade, Serbia: Centre for Applied Nonviolent Action and Strategies, 2007), pamphlet pgs. 84-93.

[xvii] Boas, Taylor, Mariela Daby, Mason Moseley, and Amy Erica Smith. “Analysis | Argentina Legalized Abortion. Here’s How It Happened and What It Means for Latin America.” The Washington Post. WP Company, January 17, 2021. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2021/01/18/argentina-legalized-abortion-heres-how-it-happened-what-it-means-latin-america/.

[xviii] Amnistía Internacional. “Por Qué Seguimos Marchando Hacia El Aborto Legal En Argentina.” Amnistía Internacional. Amnesty International, June 15, 2021. https://www.amnesty.org/es/latest/campaigns/2019/08/the-green-wave/.

[xix] Sharp, Gene “198 Methods of Nonviolent Action,” Albert Einstein Institution (December 2014), at https://www.aeinstein.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/198-Methods.pdf.

[xx] (Even though Sharp does not have social media on its 198 Methods of Non-Violence Action list, it does talk about communication strategies and social media is one.)

[xxi] Lopreite, Debora. “The Long Road to Abortion Rights in Argentina (1983–2020).” Bulletin of Latin American Research, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1111/blar.13350.

[xxii] Amnistía Internacional. “Por Qué Seguimos Marchando Hacia El Aborto Legal En Argentina.” Amnistía Internacional. Amnesty International, June 15, 2021. https://www.amnesty.org/es/latest/campaigns/2019/08/the-green-wave/.

[xxiii] Sutton, Barbara. “Reclaiming the Body: Abortion Rights Activism in Argentina.” Feminist formations 33, no. 2 (2021): 25–51.

[xxiv] Acosta, Marina. “Feminist Activism on Instagram. the Case of the National Campaign for the Right to Safe and Free Legal Abortion in Argentina.” Perspectivas de la comunicación. Universidad de La Frontera, June 2020. http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0718-48672020000100029

[xxv] Lopreite, Debora. “The Long Road to Abortion Rights in Argentina (1983–2020).” Bulletin of Latin American Research, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1111/blar.13350.

[xxvi] Srdja Popovic et al, A Guide to Effective Nonviolent Struggle, (Belgrade, Serbia: Centre for Applied Nonviolent Action and Strategies, 2007), pamphlet pgs. 84-93

[xxvii] Nuria Inés Giniger. “Abortion is law.” Kvinder, Køn & Forskning, vol. 33, no. 1, 2022. https://tidsskrift.dk/KKF/article/view/125645

[xxviii] Lopreite, Debora. “The Long Road to Abortion Rights in Argentina (1983–2020).” Bulletin of Latin American Research, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1111/blar.13350.

[xxix] Chenoweth, Erica, and Maria J. Stephan. “Chapter 2.” Essay. In Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Nonviolent Conflict, 45–61. New York: Columbia University Press, 2011.

[xxx] Lopreite, Debora. “The Long Road to Abortion Rights in Argentina (1983–2020).” Bulletin of Latin American Research, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1111/blar.13350.

[xxxi] Srdja Popovic et al, A Guide to Effective Nonviolent Struggle, (Belgrade, Serbia: Centre for Applied Nonviolent Action and Strategies, 2007), pamphlet pgs. 84-93

[xxxii] Lopreite, Debora. “The Long Road to Abortion Rights in Argentina (1983–2020).” Bulletin of Latin American Research, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1111/blar.13350.

[xxxiii] Ibid.

[xxxiv] Sutton, Barbara. “Reclaiming the Body: Abortion Rights Activism in Argentina.” Feminist formations 33, no. 2 (2021): 25–51.

[xxxv] Lopreite, Debora. “The Long Road to Abortion Rights in Argentina (1983–2020).” Bulletin of Latin American Research, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1111/blar.13350.

[xxxvi] FOS Feminista. “La Libertad Es Imparable: El Movimiento Causa Justa.” Fosfeminista.org. Fosfeminista.org, August 16, 2022. https://fosfeminista.org/media/reunion-causajusta/

Image credit: MorningStar