The gender gap looms large in financial inclusion. Across developing economies, women are six percentage points less likely than men to own bank accounts — in countries like Bangladesh, Nigeria, and Turkey, the gender gap is more than twenty percentage points. Men are more likely to report that they have saved any money in the past year and that they save through financial institutions.[i]

Abundant research shows that taking a “gender neutral” approach to design simply results in designing for men.[ii] Women tend to be more price-conscious and to want to ask more questions about new products or technologies before they make the leap.[iii] Women have different income flows, manage their financial resources differently, and have different financial goals.[iv],[v],[vi] Moreover, gendered social norms and household dynamics can make it much more challenging for women to access, take ownership of, and effectively use financial products.[vii],[viii],[ix]

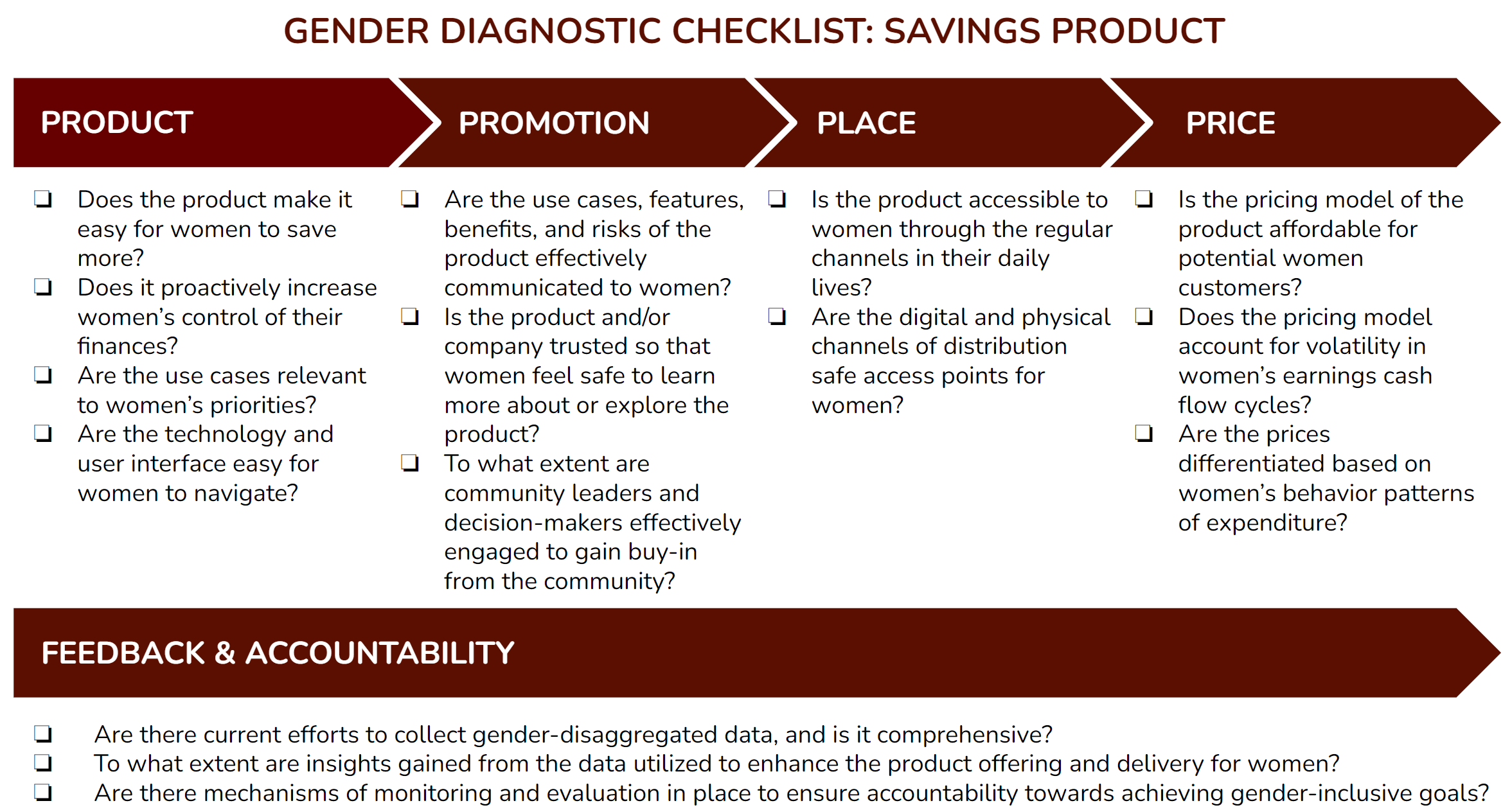

This playbook has been developed as a practitioner’s guide to help financial technology companies (fintech), microfinance institutions (MFIs), and banks better serve women. The focus of this guide is savings products, as they serve as an important gateway for many underserved women, who are excluded from credit and payment products to access formal financial channels. Given the variety of savings products out there and the diversity of women’s experiences, there is no “one size fits all” approach. What we provide here is a “gender diagnostic checklist” that highlights key questions to ask at each stage of product design and delivery, with examples of what works well. Our hope is that this will be a starting point for organizations that care about serving all of their customers to make their savings offerings as accessible and relevant as possible across genders.

1. Product

The intersection of gender and savings products sits on four key factors that determine whether such products are effective for women. First, consider whether the savings product makes it easy for women to save, given the additional financial pressures they often face. Second, examine whether these products proactively increase women’s control over their finances, given that women are more likely to experience pressure to share their money with others. Third, assess whether the product is relevant to women’s priorities, which may differ from those of men. Finally, consider the importance of user-friendly technology and interfaces for ensuring that savings products remain accessible to women, who may have lower levels of digital literacy and mobile phone ownership than men.

- Does the product make it easy for women to save more?

Saving is hard. It is painful to cut back on consumption today for some future benefit, especially for people who have scarce resources to begin with. Women are both more likely to be poor and more likely to be responsible for keeping their households running — which means spending on food, fuel, school fees – the list goes on.[x] Product design can make it more intuitive for women to put money aside whenever they are able and to keep the money for its intended purpose.

| Quick tips | Spotlights |

| Use voluntary commitment devices to reduce the temptation to withdraw money | ➔ The Green Bank of Caraga in the Philippines gave customers the option to set a target savings amount or date, before which they would not be allowed to access their savings. Those with “commitment” accounts saved 82% more. This had an especially powerful impact on women, who spent more on goods for themselves (e.g., kitchen appliances) and gained more bargaining power in their households.[xi]➔ Banco Compartamos in Mexico had customers fill out a “commitment form” stating their personal savings goal and sign it. This measure motivated customers to save.[xii] |

| Make saving the default option | ➔ India’s ICICI Bank offers a “money multiplier” program that automatically sends balances above US$150 into a separate fixed-term savings account that earns higher interest rates.[xiii]➔ A large company in Afghanistan automatically sent 5% of an employee’s paycheck into a mobile savings account. Although employees could opt out, people were 40 percentage points more likely to save than when the default was no automatic savings.[xiv] |

- Does it proactively increase women’s control of their finances?

Women are subject to greater pressure to share their money with partners, families, and friends, because they often have less status and power in their communities.[xv],[xvi],[xvii] Informally, women use strategies for retaining control such as concealing the amount of money they have or rotating savings groups as a way of preventing money from being at home.[xviii],[xix] Formal savings products can integrate features that help keep women’s savings in their hands.

| Quick tips | Spotlights |

| Leverage technological tools to increase women’s privacy | ➔ In Uganda, women who received MFI loans into their mobile money accounts (rather than in cash) had 15% higher business profits after eight months. The effect was driven by women who reported facing the most pressure to share money with their household.[xx]➔ In India, Kaleidofin enables women to discreetly check their balance through “missed calls” or choose to send messages about her account to a designated proxy outside of her household.[xxi] |

| Set up guardrails to prevent others from accessing savings | ➔ Women in India who had government wages deposited into bank accounts under their own names (rather than their husbands’) were more likely to continue working in the long run.[xxii]➔ PayCode in South Africa uses fingerprints to secure customers’ mobile money accounts. Customers can set an “alert” finger that pulls up a fake low-balance alert to ward off potential theft. This feature can also protect women from male partners asking for money.[xxiii] |

- Are the use cases relevant to women’s priorities?

Women often have different financial priorities than men. For example, when women have greater say in household spending decisions, more money tends to go towards food, school fees, and children’s clothes.[xxiv] At different points in a woman’s life, she may be more concerned with funding her own education, covering health expenses related to pregnancy and childbirth, building more working capital for her business, and so on.[xxv] To be relevant to women, savings products have to be targeted and/or framed towards their unique financial needs.

| Quick tips | Spotlights |

| Encourage women to specify what they are saving towards | ➔ In Mexico, Banco Compartamos found that asking women to set very concrete goals (e.g., saving enough money to buy a computer for the children or go on a family vacation) motivated them to keep saving. Women also found it helpful to break down their overall goal into weekly target amounts.[xxvi]➔ In Kenya, giving families storage boxes that were labelled for health expenditures increased health savings over the next year by 75%.[xxvii] |

| Target products and incentives to women’s life events | ➔ Sukanya Samriddhi accounts, backed by the Government of India, give parents robust interest rates and tax benefits to save for girls’ education.[xxviii]➔ Bancolombia offers an incentive for clients to save by providing them with medical insurance if they maintain a monthly balance of US$135 or more in their account. This insurance can be used to cover hospital treatment, including childbirth.[xxix]

➔ In Kenya, Safaricom and Kenya Commercial Bank offer M-Pesa Account, which includes two savings features. One allows users to save small change and earn higher interest in a target sub-account (e.g., for school fees), while the other locks money away for a fixed term for up to 12 months. These features enable women to manage financial volatility and access their savings instantly.[xxx] |

- Are the technology and user interface easy for women to navigate?

Women are less likely to own mobile phones than men, especially smartphones, and generally have lower literacy and digital skills.[xxxi] While smartphones and mobile wallets hold great promise for financial inclusion, it is important to ensure products remain accessible to women.

| Quick tips | Spotlights |

| Keep tech and UX simple | ➔ Mama Prime in Kenya, which helps women save for pregnancy and birth-related expenses, uses a simple USSD menu that can be used without smartphones.[xxxii] |

| Provide robust onboarding support with many different education channels | ➔ Mama Prime also trains health workers to help women enroll and learn how to use the program.[xxxiii]➔ In India, Airtel Money conducts ongoing customer education through posters, cartoon images, texts, and peer leader support, with a focus on messages and stories that women can relate to.[xxxiv]

➔ For women in Papua New Guinea, audio and video guides helped women learn more about how to use mobile technology effectively.[xxxv] |

2. Promotion

Promoting financial savings products to women is challenging due to women’s low awareness and high risk aversion. To overcome this, organizations must specifically and explicitly communicate the attributes of the product and establish trust with women. Additionally, women’s limited decision-making power in the family can also hinder their adoption of financial products. This makes it necessary to engage community leaders and decision-makers, particularly men, to secure community buy-in and support.

- Are the use cases, features, benefits, and risks of the product effectively communicated to women?

While there are proven overall and individual benefits to increasing women’s savings accounts, these linkages are often not effectively communicated to women.[xxxvi] Women’s limited awareness and understanding of the benefits of saving products, coupled with lower levels of trust, create barriers to adoption in emerging markets. Furthermore, the current framing of products may create a perceived mismatch between need and service offerings, further discouraging women’s interest.[xxxvii]

| Quick tips | Spotlights |

| Pair product with training and education programs for the female end-user and the sale agent | ➔ In two Tanzanian cities, women microentrepreneurs were provided access to an interest-bearing mobile savings platform, M-Pawa. They received twelve 2.5-hour weekly training sessions on business skills. On average, women using M‑Pawa saved three times more than women in the control group. Those in both the M-Pawa and business training groups saved almost five times more than the control.[xxxviii],[xxxix]➔ In Indonesia, Mercy Corps Indonesia showed that a business training intervention was effective in increasing the adoption of mobile savings products among female entrepreneurs. The program incentivized local bank agents to target female customers and provided them with training on the product benefits. Some female entrepreneurs were provided with financial literacy training and mentoring sessions. Women served by targeted agents increased their total savings by 7%, and women who had training increased their total savings by 11%.[xl] |

| Orient product use-cases and benefits towards women and their needs | ➔ Diamond Bank adjusted its marketing to make the product more appealing and useful for women. Initial advertising campaigns were perceived to be too male-oriented. The initial advertising campaigns were perceived to be too male-oriented, but after tweaking the marketing strategy, the bank’s female client base grew. To continue targeting female clients, Diamond Bank introduced the “Focus on Women” incentive program to reward staff for signing up new female clients.[xli] Evidence shows products designed for men often do not reach women, but products that are attractive to women can also appeal to men.[xlii]➔ Safaricom’s M-PESA in Kenya broadened its messaging towards women to emphasize use cases other than sending money.[xliii] |

- Is the product and/or company trusted so that women feel safe to learn more about or explore the product?

Increased adoption of digital financial products, specifically savings products, requires increased trust.[xliv] Due to limited resources, vulnerable social positions, and high levels of household responsibilities, women have a greater risk aversion. This leads to hesitation in adopting new technologies. Women require twice the number of interactions than men to feel comfortable using financial services independently, [xlv] and they have a higher threshold for investing in technology due to their limited resources and the increased risk they experience. [xlvi]

| Quick tips | Spotlights |

| Build company and product sentiment as dependable and trustworthy | ➔ The success story of M-PESA’s trust is largely attributed to building trust over a period of 10 years. M-PESA has prioritized ensuring that its technology is the best, no money is ever lost, and that the customer is always protected. Michael Joseph’s 10-year look back on M-PESA reflected on how trust played a significant role in the success of M-PESA.[xlvii]➔ M-Pawa has developed a reliable mobile banking solution that has been well-received by its users. According to a survey, 90% of respondents reported that they adopted M-Pawa due to its “safe” and “private” features.[xlviii] |

| Prioritize word-of-mouth marketing to build trust and acceptance to explore the product | ➔ JazzCash product had a greater percentage of active female than male customers who onboarded through referrals, indicating that referrals were a relatively effective channel for onboarding women users. Women’s World Banking collaborated with ideas42 to create and test text messages that are behaviorally informed, aiming to encourage existing JazzCash users to refer more women.[xlix]➔ Airtel Money in Malawi marketing strategy recognizes the importance of word-of-mouth recommendation. Their marketing encourages friend recommendation because it is the most important factor in influencing a decision to subscribe to mobile money.[l] Recommendations are effective because they indicate that not only was the service valuable but that the service was also understandable. Evidence also showed that women are more influenced by a friend’s recommendation than men.[li]

➔ In Bangladesh, a study on mobile banking service demonstrated that word-of-mouth recommendations play a mediating role in the relationship between trust in service providers, trust in apps, and security risks, and the intention to use the service.[lii] |

- To what extent are community leaders and decision-makers, especially men, effectively engaged to gain buy-in from the community?

Current social norms continue to restrict women’s decision-making power and limit their ability to invest and save. Women’s subordinate position in the family leads to lower decision-making power and greater pressures from their families, communities, and themselves to spend or share their money rather than invest and save.[liii] Moreover, women who try to take control of their savings may experience gender-based violence from male family members. [liv] To address this, it is important to engage men and community members in advocating for gender equality and the benefits of savings interventions for women. [lv] However, there are few savings products that actively involve male support for women. We will highlight examples from other campaigns that show promising evidence of addressing this critical component.

| Quick tips | Spotlights |

| Engage leaders to encourage community members to change attitudes and practices (child marriage campaign examples) | ➔ In Ethiopia, when the Ethiopian Orthodox Church started supporting the government’s position on the minimum age of marriage, people began to change their beliefs and practices, leading to improved norms about child marriage.[lvi]➔ In Uganda, leaders of local community organizations working with the Gender Roles, Equality, and Transformation (GREAT) project were instrumental in spreading new ideas about girls’ rights to education and delayed marriage.[lvii] |

| Target men to ensure buy-in and prevent backlash (domestic violence campaign examples) | ➔ Men As Partners provides education and skills-building workshops to men aimed at examining their attitudes towards sexuality and gender and promoting gender equality in relationships. Results of the program showed a positive impact: in pre-training interviews, 54% of men disagreed with the statement that “men must make all the decisions in a relationship,” compared to 75% who disagreed three months later.[lviii]➔ Brazil and India’s Program H includes two interventions: (1) educational sessions for six months and (2) a social marketing campaign to promote changes in norms of masculinity and lifestyles. After six months, participants that received one or both interventions were less likely to support traditional gender norms than before the intervention.[lix] |

3. Place

Two important factors must be considered to ensure that financial savings product are properly delivered to women: accessibility and safety. Women face barriers in accessing traditional and digital distribution channels due to social norms and formal structures, and this can be addressed by meeting women in channels that they already regularly access. Women also face safety concerns when accessing financial products, which can discourage them from participating in the financial system. Therefore, reducing digital and physical risks for women to access these solutions is to ensure that women can access and use savings products safely and equitably.

- Is the product accessible to women through the regular channels in their daily lives?

Women are harder to reach through traditional and digital channels to deliver financial products compared to men. This is due to social norms and formal structures that limit their ability to reach typical distribution points.[lx],[lxi] To overcome these barriers, it is important to meet women in channels that they already regularly access. For example, organizations can partner with the local community, organizations, or government programs that women frequently interact with.

| Quick tips | Spotlights |

| Reach out to women in their community and homes | ➔ Kaleidofin in India uses agents to reach women in their communities (“doorstep service”). After realizing that a lot of the women using their product don’t want their husbands to know how much they save.[lxii]➔ Paycode in South Africa scopes out rural villages before entering to identify local facilitators that can build trust. Paycode provides these facilitators with all the tools and information to onboard women on the spot.[lxiii] |

| Leverage groups are organizations that women are already a part of | ➔ Pezesha in Kenya goes through existing women’s savings groups. They developed a “group credit score” that increases as individual members display good borrowing and repayment behavior, leveraging existing networks, encouraging peer incentives, and improving group creditworthiness.[lxiv]➔ Extramile Africa in Nigeria targets informal savings groups among smallholder farmers. Upon market entry, they hold meetings with community leaders and offer agricultural technical assistance.[lxv] |

| Utilize government programs to help catalyze a more fluid interaction between women and the financial sector | ➔ In India, Pakistan, and Tanzania, government-to-persons programs successfully generate greater access to, ownership of, and usage of financial services among women, boosting their economic activity, opportunity, assets, and autonomy.[lxvi]➔ In Niger, funneling cash transfer payments to mobile accounts decreased costs of accessing the money. This improved women’s bargaining power and household consumption outcomes.[lxvii]

➔ In India, channeling workfare payments directly to women’s bank accounts rather than their husbands’ accounts has led to an increase in women’s engagement in the labor market.[lxviii] |

- Are the digital and physical channels of distribution safe access points for women?

Digital and physical safety are essential for women to save money. Unfortunately, women often face obstacles that prevent them from accessing these channels due to social, cultural, and economic factors. Some cultures prioritize women’s roles as caregivers, which can make it challenging for them to engage in financial matters that require visiting bank branches or using unfamiliar digital platforms.[lxix] Moreover, women may face various forms of physical and digital harm when accessing financial products, such as harassment, theft, or cyberattacks.[lxx] These safety concerns can discourage women from accessing financial products, resulting in exclusion from the financial system. It is important to address these barriers to ensure that women can access financial products safely and equitably.

| Quick tips | Spotlights |

| Establish appropriate measures to ensure data privacy and security for women | ➔ The Fidelity Bank “Smart Account” in Ghana that provides physically safe channels for women by making self-service less daunting and safer. Fidelity Bank collaborated with Mistral Mobile, run by former Nokia mobile staff, to create a user-friendly interface that is less intimidating for low-income clients. Additionally, the use of encrypted SMS makes the self-service channel more secure for customers, especially women.[lxxi] |

| Provide channels that are physically safe for women | ➔ Kaleidofin in India acknowledges the significance of social structures and prioritizes discretion and privacy in its service delivery. To ensure women’s privacy and security, customers have the option to check their account balance via ‘missed calls’ and appoint a non-household proxy to receive account-related messages.[lxxii]➔ Diamond Bank and Women’s World Banking created BETA Savings, a digital savings account designed to provide a safe and convenient savings option for women. BETA Savings offers doorstep banking through agents called “BETA Friends” and has over 200,000 clients. “BETA Friends” visit the markets and allow clients to deposit or withdraw money regularly using mobile technology.[lxxiii] |

4. Price

Women’s unique expenditure and income patterns mean that affordability is a critical concern for them. Women often experience greater income volatility due to factors such as lower pay, fewer promotions, more informal jobs, and less job security. Additionally, women tend to prioritize long-term savings goals such as education, healthcare, and retirement. This means that interest rates, withdrawal penalties, and other pricing factors should reflect women’s needs and preferences. By taking these unique cash flow cycles into account, a savings product can be made more accessible and affordable to potential women customers.

❏ Is the pricing model of the product affordable for potential women customers?

Setting prices that are affordable and accessible to women, such as determining interest rates on deposits, minimum balances, registration fees, or bank charges, is crucial to bridging the financial inclusion gender gap. Women are generally cost-conscious and keenly aware of the added expenses, such as transport costs, opportunity cost of leaving their business to go to a bank or financial institute, etc., involved in accessing financial services.[lxxiv] Affordability is a major concern for women, who face greater financial challenges than men due to their lower labor force participation rate – which is approximately 47% globally compared to 72% for men – as well as their lower earnings rate, with women earning only 77 cents for every dollar earned by men.[lxxv],[lxxvi],[lxxvii]

| Quick tips | Spotlights |

| Remove costs that put additional burden on women’s capacity to save, or determine costs based on women’s contextual paying preferences | ➔ In Nigeria, the Diamond Bank’s BETA products cater to low-income women entrepreneurs by offering affordable doorstep services through a network of agents called BETA friends, without charging additional fees.[lxxviii]➔ In Colombia, Banco WWB introduced YoAhorro in 2011, initially for its existing borrowers, and later expanded to other segments. Within a year, the product gained more than 100,000 active accounts. YoAhorro is a free account with a low minimum balance requirement, allowing customers to transact at branches using biometric equipment instead of a debit card. This feature eliminates the monthly fee charged by most Colombian banks.[lxxix]

➔ In Nepal, a research pilot demonstrated that reducing transaction fees and increasing the proximity of accounts led to a significant increase in women’s account activity. However, in Kenya, studies showed that technologies that reduce transaction costs and make account balances more accessible might favor those who have more bargaining power in the household, usually men. To make accounts more attractive to women, incorporating additional security features like biometric scanning into transaction-cost-reducing technologies could be a promising solution.[lxxx] |

❏ Does the pricing model account for volatility in women’s earnings cash flow cycles?

Women are more susceptible to risks because their life cycles differ from men’s. They earn less, receive fewer promotions, stop getting raises earlier, have less secure jobs, and have lower bargaining power.[lxxxi],[lxxxii],[lxxxiii] This volatility in women’s earnings should be captured in the pricing model of the savings product, as deposit amounts will be largely determined by the informal nature of women’s incomes.

| Quick tips | Spotlights |

| Provide flexibility in deposit amounts and timelines | ➔ In India, SEWA’s cooperative catered to women in the informal economy by allowing for the deposits to be as low as 10 INR (~15 cents USD) that can be made on a daily, weekly, biweekly, or monthly basis.[lxxxiv]➔ In Malawi, Pafupi allows small deposits, charges no monthly fees, and operates through agents in conveniently located rural shops. This gender-conscious approach has led to an increase in uptake not only by women but has also attracted men, making a business case for gender-inclusive design to be the only way to cater to all populations.[lxxxv] |

| Offer small incentives that provide security, such as overdraft protection, insurance, access to savings during emergencies, etc. | ➔ In India, Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana (PMJDY) accounts offer additional financial features such as overdraft protection, insurance, and government cash transfer protection. These accounts saw a significant rise in usage during the COVID-19 pandemic as many women accessed the accounts for cash transfers and emergency credit.[lxxxvi]➔ Kenya’s KCB M-Pesa offers partition accounts that accrue higher interest. These accounts enable women to access loans for essential tasks like paying their child’s school fees or hospital bills.[lxxxvii]

➔ In Colombia, Bancolombia’s “Ahorro a la Mano” is a mobile-opened zero-balance interest-bearing account that offers a medical insurance plan that covers hospital treatment and childbirth if women’s monthly savings reach $135 or more.[lxxxviii] ➔ Telenor Microfinance Bank in Pakistan offers its customers free life insurance coverage if they maintain a certain level of savings in their account or if they are a prepaid subscriber.[lxxxix] |

❏ Are the prices differentiated based on women’s behavior patterns of expenditure?

Women tend to prioritize spending their savings on things like food, healthcare, and education, while men are more likely to prioritize spending on transportation, entertainment, and hobbies. [xc] Women are more likely to think about long-term financial planning, such as retirement savings, and they live longer.[xci],[xcii] Thus, their expenditure or withdrawal needs differ from men. Therefore, interest rates, incentives, and penalties for withdrawal should reflect women’s preferences for price and liquidity.

Women’s unique expenditure and income patterns mean that affordability is a critical concern for them. Women often experience greater income volatility due to factors such as lower pay, fewer promotions, more informal jobs, and less job security. Additionally, women tend to prioritize long-term savings goals such as education, healthcare, and retirement. This means that interest rates, withdrawal penalties, and other pricing factors should reflect women’s needs and preferences. By taking these unique cash flow cycles into account, a savings product can be made more accessible and affordable to potential women customers.

| Quick tips | Spotlights |

| Offer price differentiation based on women’s unique life events and responsibilities, such as pregnancy, childcare, etc. | ➔ Mama Prime in Kenya designed its maternity savings and credit product with two distinct user experiences — one for its female customers and one for its hospital partners. For its female users, the product offers three easy options to make affordable down payments – “pay any amount, anywhere, anytime.”[xciii]➔ Banco WWB in Colombia offers a savings product that promotes goal-based savings for education, housing, or smaller personal goals. The product is offered at no fee and incorporates cost-saving measures such as mobile banking to further reduce costs. The account leverages growing savings balances as a source of funding for on-lending.[xciv] |

5. Data/Feedback

Collecting, applying, and tracking gender-disaggregated data is essential for designing gender-conscious financial products. Collecting this data is foundational as it provides insight into women’s banking behaviors, effective channels, and solutions. Applying insights from gender-disaggregated data enables organizations to tailor their product development and marketing strategies to better serve female customers. Tracking gender-sensitive KPIs through regular monitoring and evaluation is crucial to ensure accountability toward gender-inclusive goals and avoid bias against women.

❏ Are there current efforts to collect gender-disaggregated data, and is it comprehensive?

Gender-disaggregated data collection is foundational to designing gender-conscious financial products. It provides insights into women’s banking behaviors, effective channels, and solutions. However, the lack of quality gender-disaggregated data is currently a significant issue. If it is happening, there are errors such as double counting and non-standard definitions. Disaggregated data can be used for various purposes, including management reporting, business development, marketing or PR, product development, benchmarking performance, and high-level strategic decision-making. All of this would help financial savings product tailor to the needs of their female customers.

| Quick tips | Spotlights |

| Leverage existing gender-performance frameworks to evaluate gender specific data quality | ➔ In Nigeria, Diamond Bank developed women-focused data indicators using Women’s World Banking’s Gender Performance Indicators[xcv] to evaluate and manage their BETA agents’ performance. This exercise helped them generate insights, including the insight that their products served both men and women equally but generated 50% more transactions for men clients.[xcvi] |

| Build on existing data collection methods by analyzing both demand-side data, including women’s financial needs and behaviors, and supply-side data, including product uptake and effectiveness | ➔ “In India, Jan Dhan accounts collected sex-disaggregated data, but reporting was limited to the portfolio level, hindering gender-specific insights. The Jan Dhan Plus pilot project introduced a data disaggregation framework that monitored savings balances, transaction behaviors, NPAs, savings and credit behaviors, product penetration, and access. This enabled a more comprehensive analysis of women’s savings and credit behaviors, withdrawal and deposit patterns, and payment channels.[xcvii]➔ In Chile, the Superintendencia de Bancos e Instituciones Financieras (SBIF) initially relied on credit registry data to obtain sex-disaggregated information, as every borrower has a gender-coded national ID number. After three years, SBIF began directly requesting sex-disaggregated savings data from financial service providers. To ensure that the data was accurately collected and reported, SBIF worked closely with these providers.[xcviii] |

❏ To what extent are insights gained from the data utilized to enhance the product offering and delivery for women?

Data is not powerful alone; the application of data is powerful. By analyzing data on women’s financial behaviors, preferences, and product usage patterns, financial institutions can tailor their product offerings and delivery channels to better serve female customers. However, there is still a gap in the extent to which institutions are utilizing these insights to inform their product development and marketing strategies. Effectively utilizing gender-disaggregated data insights can result in better product-market fit, increased customer satisfaction, and improved financial inclusion for women.[xcix],[c]

| Quick tips | Spotlights |

| Apply insights to improve product offering to cater to women | ➔ In India, Dvara KGFS uses data gathered from women’s personal experiences to build a model based on a deep understanding of their unique needs. Women share their goals, challenges, and household circumstances during the enrollment process. By giving women the ownership of their stories, Dvara KGFS is able to identify and address the real issues that affect their clients and use this information to improve their services.[ci] |

| Apply insights to inform go-to-market strategy to reach women | ➔ JUMO is a technology company that develops financial services platforms in several countries, including Ghana, Zambia, Kenya, Pakistan, and Uganda. By applying a gender lens to their customer data, JUMO discovered that they were not effectively reaching women due to structural barriers such as work and living arrangements. As a result, JUMO identified an impact fund that specifically catered to the needs of these women, enabling them to better serve this underserved market.[cii] |

❏ Are there mechanisms of monitoring and evaluation in place to ensure accountability toward achieving gender-inclusive goals?

Gender-sensitive KPIs are crucial to ensure accountability toward gender-inclusive goals. KPIs can be set to track progress towards improving product-market fit and increasing customer satisfaction for women. Regular monitoring and evaluation of these KPIs will enable improvements to their product offerings and delivery channels. A gender lens on all metrics is important to avoid bias against women.

| Quick tips | Spotlights |

| Report your score on gender equality performance | ➔ Bloomberg’s Gender Equality Index enables investors to assess the performance of financial institutions and other companies in relation to their gender equality commitments. Transparent reporting on these metrics helped companies identify blind spots, strengthen accountability, and incentivize businesses to prioritize inclusion for women.[ciii] |

Conclusion

Women’s financial inclusion has a strong link to women’s economic empowerment. There is also a strong business case for financial institutions to serve women and unlock new markets, as they are traditionally underserved. However, this requires acknowledging that gender-norms affect women’s ability to access, use, and benefit from financial services. Financial institutions can thus be a catalyst for achieving women’s economic empowerment by designing and delivering products that keep women’s opportunities and constraints in mind, not just as an afterthought but by embedding tools in each step of the product cycle.

References

[i] Global Findex Database (2021). Financial Inclusion, Digital Payments, and Resilience in the Age of COVID-19

[ii] Caroline Criado-Perez (2019). The deadly truth about a world built for men

[iii] Women’s World Banking (2017). Successful by design

[iv] UN Women (2016). Women in informal economy

[v] CGAP (2016). Women’s financial inclusion: A down payment on achieving the SDGs

[vi] Viviana Zelizer (2011). The gender of money

[vii] Emma Riley (2020). Resisting social pressure in the household using mobile money

[viii] Arielle Bernhardt et al (2018). Male social status and women’s work

[ix] Erica Field (2016). Friendship at work: Can peer effects catalyze female entrepreneurship?

[x] IMF (2012). Empowering women is smart economics

[xi] J-PAL (2003). Commitment savings products in the Philippines

[xii] Women’s World Banking (2020). Adapting the group lending model for individual savings

[xiii] Women’s World Banking (2015). Digital savings: The key to women’s financial inclusion?

[xiv] IPA (2017). Nudges for financial health

[xv] UN Women (2015). The world’s women 2015: Trends and statistics

[xvi] Simone Schaner (2016). The cost of convenience?

[xvii] Suresh de Mel, David McKenzie & Christopher Woodruff (2009). Are women more credit constrained?

[xviii] Nathan Fiala (2017). Business is tough but family is worse

[xix] Siwan Anderson & Jean-Marie Baland (2002). The Economics of Roscas and Intrahousehold Resource Allocation

[xx] Emma Riley (2020). Resisting social pressure in the household using mobile money

[xxi] DFS Lab (2019). How three companies are making fintech work for women

[xxii] Erica Field et al (2019). On her own account: How strengthening women’s financial control affects labour supply and gender norms

[xxiii] Center for Financial Inclusion (2021). The case for gender-inclusive fintech

[xxiv] Viviana Zelizer (2011). The gender of money

[xxv] IPA (2017). Women’s economic empowerment through financial inclusion

[xxvi] Women’s World Banking (2020). Adapting the group lending model for individual savings

[xxvii] Pascaline Dupas & Jonathan Robinson (2013). Why don’t the poor save more?

[xxviii] Global Partnership for Financial Inclusion (2020). Advancing women’s digital financial inclusion

[xxix] Women’s World Banking (2015). Digital savings: The key to women’s financial inclusion?

[xxx] Reuters (2019). Kenya’s Safaricom tests new mobile savings service

[xxxi] GSMA (2020). The mobile gender gap report

[xxxii] DFS Lab (2019). How three companies are making fintech work for women

[xxxiii] DFS Lab (2019). How three companies are making fintech work for women

[xxxiv] GSMA (2016). Connected women

[xxxv] Ibid.

[xxxvi] Financial Times (2018). Even women who can handle money are reluctant investors

[xxxvii] GSMA (2013). Unlocking the Potential: Women and Mobile Financial Services in Emerging Markets

[xxxviii] CGDev (2018). Mindful Saving: Exploring the Power of Savings for Women

[xxxix] Ibid.

[xl] WorldBank (2018). Helping poor women grow their businesses with mobile savings, training, and something more?

[xli] CGAP (2013). Banking on Including Women

[xlii] Women’s World Banking (2017): : Successful by design: Why creating product for women in a win-win

[xliii] GSMA (2013). Unlocking the Potential: Women and Mobile Financial Services in Emerging Markets

[xliv] USAID (2018). The Role of Trust

[xlv] GSMA (2014). Reaching Half the Market: Women and Mobile Money

[xlvi] Women’s World Banking (2015). Digital savings: The key to women’s financial Inclusion?

[xlvii] CNET (2017). Kenya’s been schooling the world on mobile money for 10 years

[xlviii] CGAP (2015). M-Pawa 1 Year on: Mobile Banking Perceptions, Use in Tanzania

[xlix] Women’s World Banking (2018). It’s as Easy as A-B-C! How A/B Testing Helped Onboard More Women Customers through Mobile Account Referrals

[l] Academia (2004). Marketing Strategy of Airtel

[li] All Africa (2016). Malawi: Airtel Money Users Hits One Million Figure

[lii] Rahman T, Noh M, Kim YS, Lee CK. Effect of word of mouth on m-payment service adoption: a developing country case study. Information Development. March 2021. doi:10.1177/0266666921999702

[liii] CGDev (2018). Mindful Saving: Exploring the Power of Savings for Women

[liv] WHO (2009). Promoting Gender Equality to Prevent Violence Against Women

[lv] ILO (2016). Engaging Men in Women’s Economic Empowerment and Entrepreneurship Development Interventions

[lvi] ODI (2015). How Do Gender Norms Change?

[lvii] Ibid.

[lviii] International Journal of Men’s Health (2004). The men as partners in South Africa: reaching men to end gender-based violence and promote sexual and reproductive health

[lix] Washington, DC, Population Council, (2006). Promoting gender-equity among young Brazilian men as an HIV prevention strategy. Horizons Research Summary

[lx] Cheema et al (2020). Glass Walls: Experimental Evidence on Access Constraints Faced by Women

[lxi] Women’s World Banking (2016). Women’s Financial Inclusion: A Driver for Global Growth

[lxii] DFS Lab (2019). How three companies are making fintech work for women

[lxiii] CFI (2021). The Case for a Gender-Intelligent Approach: An Opportunity for Inclusive Fintechs

[lxiv] DFS Lab (2019). How three companies are making fintech work for women

[lxv] CFI (2021). The Case for a Gender-Intelligent Approach: An Opportunity for Inclusive Fintechs

[lxvi] World Bank (2020). Digital Cash Transfers in the Time of COVID 19

[lxvii] Sarah Hendriks (2019) The role of financial inclusion in driving women’s economic empowerment, Development in Practice, 29:8, 1029-1038, DOI: 10.1080/09614524.2019.1660308

[lxviii] Ibid.

[lxix] White Swan Foundation (2018). Why Caregiving Needs to be De-Feminized

[lxx] Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (2023). Cyber Resilience Must Focus On Marginalized Individuals, Not Just Institutions

[lxxi] Women’s World Banking (2015). Digital Savings: The Key to Women’s Financial Inclusion?

[lxxii] DFS Lab (2019). How three companies are making fintech work for women

[lxxiii] Women’s World Banking (2015). Digital Savings: The Key to Women’s Financial Inclusion?

[lxxiv] Women’s World Banking (2018). How to create financial products that win women

[lxxv] Women’s World Banking (2017), Successful by design: Why creating product for women in a win-win

[lxxvi] International Labour Organization (2022). The gender gap in employment: What’s holding women back?

[lxxvii] Forbes (2023). Gender Pay Gap Statistics In 2023

[lxxviii] Women’s World Banking (2014). Diamond Bank Storms the Market: A BETA Way to Save

[lxxix] Women’s World Banking (2013): Savings: A Gateway to Financial Inclusion

[lxxx]Dartmouth (2011). The Cost of Convenience? Transaction Costs, Bargaining Power, and Savings Account Use in Kenya

[lxxxi] Ellevest (2022). The Gender Pay Gap: What to Know and How to Fight It

[lxxxii] Payscale (2019) Earnings Peak at Different Ages for Different Demographic Groups

[lxxxiii] New York Times (2020). Young Men Embrace Gender Equality, but They Still Don’t Vacuum

[lxxxiv] Platform Cooperativism Consortium (2018). “We Are Poor but So Many”: Self-Employed Women’s Association of India and the Team of the Platform Co-op Development Kit Co-Design Two Projects

[lxxxv] UNCDF (2022). Microlead: Malawi

[lxxxvi] CGAP (2021): Catalyzing Women’s Bank Account Use Through COVID-19 Relief

[lxxxvii] Safaricom (2022). KCB M-PESA Account

[lxxxviii] Women’s World Banking (2015). Digital Savings: The Key to Women’s Financial Inclusion?

[lxxxix] MicroCapital (2013). MicroEnsure, Telenor Pakistan, Jubilee Life Insurance Company to Offer Free Life Insurance to Prepaid Mobile Customers in Pakistan

[xc] Clinton Global Initiative (2010). Clinton Global Initiative: Empowering Girls & Women

[xci] UBS (2021). Women’s Wealth Report

[xcii] PRB (2001). Around the Globe, Women Outlive Men

[xciii] DFS Lab (2019): How to design fintech products for women

[xciv] Women’s World Banking (2013). Savings: A Gateway for Financial Inclusion

[xcv] Women’s World Baking (2015). Gender Performance Indicators

[xcvi] Women’s World Banking (2015). Digital Savings: The Key to Women’s Financial Inclusion?

[xcvii] Women’s World Banking (2013). The Power of Jan Dhan: Making Finance Work for Women in India

[xcviii] UNCDF. Sex-disaggregated supply-side data: how to begin?

[xcix] IMF (2022). IMF Strategy Toward Mainstreaming Gender

[c] The World Bank (2016). More and Better Gender Data: A Powerful Tool for Improving Lives

[ci] Ibid.

[cii] Accion (2021). Leveraging data to close the digital gender divide

[ciii] Bloomberg (2023). Gender Equality Index

Image credit : ILO