This paper focuses on on the development of transnational and diplomatic relations between Singapore and China from 1965 to 1975 as approached from a Singaporean perspective. This decade-long period is marked by two key events: 1) The separation of Singapore from Malaysia in 1965 to become an independent state with the new responsibility of establishing its foreign policy within the Cold War world order; and 2) The establishment of Singapore’s first diplomatic-level contact with the People’s Republic of China when Foreign Minister S. Rajaratnam visited Beijing in 1975. In 1965, Singapore and China were mutually distrustful and politically opposed—the virulently anti-communist People’s Action Party (PAP) feared China’s involvement in supporting communist movements in Southeast Asia, and Chinese media criticized Singapore as a “running dog of US imperialism” that had turned its back on its motherland.[1] How did the two countries so at odds politically in 1965 navigate shifting international dynamics and national goals to the point where diplomatic-level contact between Singapore and China was established in 1975?

Singapore and China would not officially normalize diplomatic relations until 1990, fifteen years later—but this period represents a crucial shift in warming relations between the two countries, laying the groundwork for future cooperation. Rajaratnam’s 1975 state visit was followed by Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew’s trip to China the next year; Deng Xiaoping visited Singapore in 1978 and often praised the country’s model of economic development. The two nations would go on to embark on joint ventures such as the much-vaunted China-Singapore Suzhou Industrial Park (SIP) in 1994, the 25thanniversary of which project was celebrated earlier this year as a symbol of the continued friendship between the two nations.[2]

The history of Singapore-China relations has been explored through a number of approaches, though none has so far explored the time period from 1965-75 in an international context. Studies of Singapore-China bilateral relations do not give direct attention to this period: Linda Yip Seong Chun’s Bibliography of ASEAN-China Relations, for example, lists one source titled “Sino-Singaporean Relations, 1965-1976,” an undergraduate paper that was never published; the inclusion of this source suggests the paucity of reliable academic literature covering this topic.[3] Furthermore, a narrow focus on Singapore-China bilateral relations does not provide sufficient context on Singapore’s wider foreign policy goals or take into account the immense influence of Cold War players in shaping the trajectory of Singapore-China relations. Beyond a narrow focus on Singapore-China bilateral relations, the events of the decade from 1965-1975 must also be understood against the backdrop of the Cold War, taking into account Singapore and China’s relations vis-à-vis other countries in this period. To this end, I will draw upon scholarship of Singapore’s foreign policy including Michael Leifer’s Singapore’s Foreign Policy: Coping with Vulnerability. In order to devote due attention to the influence of the interplay between powers on Singapore’s foreign policy interaction with China, I will synthesize sources that focus on Singapore’s bilateral relations with nations other than China as well as China’s bilateral relations with other world powers: for example, Bilveer Singh’s analysis of Singapore-Soviet relations[4] and Robert Horn’s contemporary commentary on Sino-Soviet competition in Southeast Asia, among others.[5] In addition to synthesizing the secondary literature discussed above, I will draw on Singaporean and Chinese news archives, records of political figures, and contemporary foreign policy analyses to fill in the gaps in the existing narratives. Focusing on Singapore, I will argue that the development of Singapore-China relations during this period can best be understood not merely as a bilateral relationship but as one situated in a complex web of international political dynamics, both in relation to Cold War powers—namely, the US and the USSR—and within Southeast Asia. Singapore’s pragmatic foreign policy outlook—one that gave priority to economic security and the balancing of international and regional powers—in turn influenced Singapore’s engagement with China and its reaction to these broader Cold War dynamics.

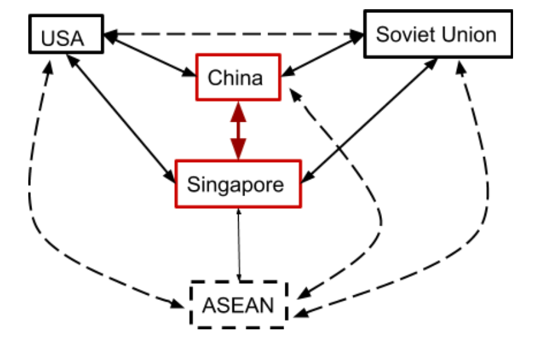

Figure 1. The International Context of Singapore-China Relations. Image created by author.

This diagram of the relationships among the major players surrounding Singapore’s bilateral relations with China in the period from 1965-75 illustrates the complexity of the foreign policy situation. Untangling this network of interactions in its full complexity presents a daunting challenge, and teasing out every thread of this web is beyond the scope of my research. For the purposes of this paper, with the goal of assembling a historical narrative of the international dynamics at play in the Singapore-China relationship, I have laid out my argument in the following five thematic sections:

1) Singapore’s foreign policy outlook and the foundations of Singapore-China relations; 2) the role of the USSR: Sino-Soviet competition in Southeast Asia; 3) the role of the US: the Nixon Doctrine and US-China Rapprochement; 4) the role of ASEAN: neutralization and regional tensions; and 5) Minister Rajaratnam’s visit to China.

Singapore’s Foreign Policy Outlook and the Foundations of Singapore-China Relations

On August 9, 1965, Singapore officially seceded from the Federation of Malaysia to become an independent state. The split from Malaysia was sudden and unanticipated—Singapore had merged with Malaysia less than two years prior, until a series of ethnic, political, and economic conflicts between Singapore and the Malaysian government led to the union’s rapid collapse. Singapore’s independence placed the country in a precarious position of vulnerability on the world stage due to a compounding series of geographic, political, and economic concerns. The clearest indicator of Singapore’s vulnerability is its size: At 725.1 square kilometers, Singapore’s land area is approximately 1/450ththe size of its closest neighbor, Malaysia. The location of Singapore, sandwiched between Malaysia and Indonesia, its other large neighbor, left the island nation with an acute sense of insecurity with respect to these regional powers—which had respectively a majority Malay and Javanese ethnicity in contrast to Singapore’s majority Chinese population. While Singapore’s natural deep harbor and access to the Straits of Malacca created economic opportunity, it also left the nation overwhelmingly dependent on entrepôt trade as a main economic activity.

Newly independent and unexpectedly thrust into a world ensnared by Cold War tensions, Singapore’s early leaders were faced with the daunting task of guiding the nation’s foreign policy and interactions with global and regional powers. In Singapore’s Foreign Policy: Coping with Vulnerability, Michael Leifer argues that the nation’s foreign policy outlook at the time was guided by an urgent imperative to secure its national interests in the face of these weaknesses, writing, “the government of Singapore…has never taken the island-state’s sovereign status for granted; a supposition which has been registered in a practice of foreign policy predicated on countering an innate vulnerability.”[6]

In practice, Singapore’s foreign policy outlook from 1965 to 1975 can be characterized in two ways: first, it was driven by profound pragmatism and economic focus that was at times at odds with Singapore’s professed rhetoric; second, it required a balancing of powers—navigating relationships with the big powers and regional powers, and playing these actors off against each other. Singapore’s first public declaration of its foreign policy came two days after its independence, with Rajaratnam’s pronouncement that Singapore “would take a non-alignment stance in the ‘power struggle’ between the Communist and Western blocs.” [7] In Leifer’s analysis, following this declaration of non-alignment, Singapore’s leaders continued to articulate “ideal goals of foreign policy” in order to ensure the “international acceptability of the island-state, especially among Afro-Asian countries,” but in actuality, foreign policy was enacted in ways that would benefit Singapore’s geopolitical situation and economic interests. “To this end, for example, Singapore found no difficulty in reconciling a declaratory non-alignment with a cooperative and lucrative relationship with both the USA and the government of South Vietnam during the late 1960s.”[8] This policy reflects the Singaporean leadership’s acknowledgement that its sovereignty and domestic security depended on its economic prosperity.

This pragmatism and focus on economic relations are reflected in Singapore’s unbroken trade relationship with China from 1965 onwards. Ideologically, the two nations were diametrically opposed—Singapore’s independence was predicated on its strong anti-communist stance and ability to stave off the threat of communist insurrection; the Chinese Communist Party viewed its support of the Malayan Communist Party, which directly challenged Singapore’s sovereignty, as an obligation in service of the Chinese-led international communist revolution.[9] In the face of this dilemma, Singapore decided, “entrepôt trade with China was a tangible asset…it could not afford to discard.”[10] Therefore, despite these intractable differences in ideology and geopolitical interests, Singapore forged ahead under a system that appeared to separate foreign policy from trade policy. Singaporean Foreign Minister S. Rajaratnam announced in 1965, “Singapore, now it has become independent, is most interested in maintaining and consolidating trade links with China as with other friendly countries, which recognise our independence and political integrity.”[11]

This desire to strengthen trade was reciprocated by China, as is reflected clearly in the numbers: the total value of Singapore’s trade with China nearly doubled from 246.9 million SGD in 1965 to 408.9 million SGD the next year. By 1974, the total value had more than tripled from 1965 figures to 786.2 million SGD.[12] In the late 1960s, the PRC “ranked in approximately sixth place” as a trading partner for Singapore by volume,[13] and in 1975 Singapore and Malaysia comprised the second most important market for Chinese manufactures after Hong Kong.[14] John Wong, writing in 1975, notes that Singapore is one of the few countries, regardless of political ideology, “which [has] successfully maintained trade relations with China, virtually continuously, in spite of political pressure.”[15] Indeed, between 1965 and 1975, Singapore occupied a unique trading position with respect to China: it hosted the only remaining branch of the Bank of China in Southeast Asia, and trade continued despite the suspension of Chinese trade relations on the part of Southeast Asian nations including Thailand, the Philippines, and Indonesia during this period.[16]

Singapore’s pragmatic strategy must be understood in the context of the leadership’s national security response to its vulnerabilities. As Latif writes, “economic links with the rest of the world are as crucial as physical security to an island trading-state.”[17] Although Singapore’s economic relations in practice may not have aligned with its foreign policy statements, in actuality trade policy and foreign policy were not decoupled—they were “inextricably linked”—and in order to maintain economic stability and hence national security, “what [was] required [was] a balance among the great powers which can keep the peace.”[18] In order to prevent the domination of Singapore by its regional neighbors or by any single superpower, Singapore’s goal was to attract the interest of international powers in Singapore and encourage the presence of these powers in Southeast Asia—and establishing economic relationships was a key means to achieve this goal. In the words of Lee Kuan Yew, “the [balance of power] policy depends on the competing interests of several big powers in the region, rather than on linking the nation’s fortunes to one overbearing partner. The big powers can keep one another in check, and will prevent any one of them from dominating the entire region, and so allow small states to survive in the interstices between them.”[19] The intricacies of this big power competition between the Cold War powers in relation to Singapore and Southeast Asia, and the resulting implications for Singapore-China relations, are discussed below.

The Role of the USSR: Sino-Soviet Competition in Southeast Asia

In the 1960s, the Soviet Union was keen to gain a foothold in Southeast Asia and strengthen its presence in the region. Prior to 1965, Soviet attention in the region was focused on Indonesia—but after the sudden regime change in which Indonesia’s pro-communist faction lost power, the Soviet Union was forced to turn elsewhere to expand its Southeast Asian presence.[20]In the eyes of the Soviets, Singapore was an obvious choice—due to the importance of its port to international trade, Singapore was a key area of interest in the region. Singapore was also eager to “entice to entice the superpower’s economic and political interest in Singapore.” Shortly after independence, “Deputy Prime Minister Toh Chin Chye led a delegation to Moscow that made agreements to set up a trade mission and a TASS [Telegraph Agency of the Soviet Union]office in Singapore.”[21] Following a 1966 trade agreement, Singapore and the Soviet Union established the Singapore-Soviet Shipping Agency (SINSOV) in 1967, the “first Soviet joint venture in the region.”[22] In June 1968, the two nations officially established diplomatic relations. The value of the Soviet relationship to Singapore was clear—not only would the joint shipping venture allay Singapore’s fears of Malaysia and Indonesia dominating the Straits of Malacca, in line with the balance of powers strategy, Soviet presence would also “fulfill Lee Kuan Yew’s call for a multipower [sic] presence in the region and could persuade the United States to remain.” [23]

During the same period, Sino-Soviet relations had deteriorated rapidly, leading to the Sino-Soviet split that would fundamentally reshape the dynamics of the Cold War. Tensions between the two powers had been accumulating since the mid-1950s, partly as a result of a breakdown in communications between Beijing and Moscow in the wake of the death of Stalin, the Taiwan Strait Crises, and the Great Leap Forward. In addition to issues of national security, the two powers increasingly clashed on an ideological front as they vied for the leadership of the international communist movement.[24] After a series of conflicts in the 1960s, relations between China and the Soviet Union reached a nadir in 1969 with the eruption of a bloody conflict along their shared border.[25] At the time, China was emerging from the internal chaos of the Cultural Revolution, and once again turning its attention to the world—this time with“a more moderate and more pragmatic…foreign policy, somewhat less identified with militant ideology and the spread of violent revolution and more interested in traditional state-to-state relations.”[26] The two powers, once fraternal, now faced each other as fierce competitors in the international arena.

As Sino-Soviet competition intensified, China’s changing international orientation increasingly threatened Soviet interests in Southeast Asia.Melvin Gurtov notes that according to a contemporary Soviet commentator, “Brezhnev was concerned that China’s leaders had not abandoned their aim to establish an anti-Soviet third-world bloc, which China [was] historically, economically, and geographically well situated to attempt.”[27] In June 1969, Brezhnev first put forth his proposal for a system of Asian “collective security,” in which the Soviet Union proposed an alliance that would safeguard Asian interests. This proposal was vague and offered neither assurances of political nor military support—in fact, “collective security” was viewed by foreign policy analysts at the time as “nothing more than a convenient peg on which to hang [an expression of interest in Southeast Asia]” and to send a challenge to China.[28] Unsurprisingly, the Chinese leadership vehemently criticized Brezhnev’s proposal. Their opposition to the plan is made clear in an article published in the Peking Review, an English-language government magazine geared at an international audience. In the eyes of China, “the ‘Asian collective security system’…is designed to serve nothing but the Kremlin’s policies of aggression and expansion. It is contrived for the purpose of contending with the United States for hegemony in Asia, dividing the Asian countries, and bringing small and medium-sized Asian countries into their sphere of influence.”[29]

This outrage in response to Soviet overtures in Southeast Asia led directly to a significant warming of China’s attitude towards Singapore. Citing the memoirs of Lee Kuan Yew, Latif writes, “in late 1970…Beijing quietly changed its attitude to Singapore because it wanted as many countries as possible to check the expansion of the Soviet Union’s influence into Southeast Asia.” He goes on to claim that it was at this juncture that China recognized Singapore’s independence.[30] News reports from the Singaporean media in 1971, however, made repeated reference to the fact that China had thus far refused to recognize Singapore as an independent nation, with one commentator suggesting that this posed the biggest obstacle to Singapore-China relations at the time. [31] An analysis of the online archives of the 人民日报(People’s Daily), the official mouthpiece of the CCP, reveals that while China may not have publicly recognized Singapore’s independence, there was in fact a dramatic shift in coverage of Singapore in 1970 that could indicate a change in China’s policy towards Singapore. The term “李光耀傀儡集团,” translated as the “Lee Kuan Yew clique,” a derogatory term meant to convey the illegitimacy of the Singaporean leadership, appeared in 20 articles in 1968, 15 articles in 1969, and 9 articles in 1970—yet after the end of August in 1970, the term was never used again. This dramatic shift is reflected in the tone of articles, which change from polemics boldly attacking the Singaporean regime to benign news reports expressing friendship.[32] This change in Chinese attitude towards Singapore eased tensions between the two countries, paving the way 1971 for a delegation from the Singaporean Chinese Chamber of Commerce to visit the People’s Republic of China for the first time and to meet with trade representatives in order to further Singapore’s economic interests in China.[33] This trip represented the beginning of friendly exchanges between Singapore and China that set the precedent for future visits of a diplomatic nature, just as Ping-Pong Diplomacy had set the stage for Nixon’s visit to China in 1972.

The role of the US: the Nixon Doctrine and US-China Rapprochement

Since the early days of Singapore’s independence, the nation’s leadership has welcomed American presence in Southeast Asia as a means of upholding the balance of power in the region. Despite some initial anti-American sentiment, Singapore came to support U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War by 1967.[34] Although Singapore did not extend direct military support to the United States, it did offer to serve as a recreation base for U.S. soldiers during the war. This gesture of friendship is explained by the fact that despite “mixed feelings” within the Singaporean leadership regarding U.S. military engagement in Vietnam, “there was an underlying approval for a U.S. military role as a basis for upholding the independence of regional states.”[35] In the context of the Vietnam War, Singapore was “[concerned] that a US withdrawal would lead to a Communist victory in Vietnam and provide fresh encouragement to local communist parties elsewhere in Southeast Asia.”[36] Singapore’s policy can be seen as driven by pragmatic regional power concerns rather than a true ideological or political identification with the United States—yet the latter was exactly how the Chinese perceived it. A 1968 article in the人民日报, or People’s Daily, excoriates Singapore for its support of the US presence in Vietnam. Its attitude is abundantly clear in the title: “Malayan newspaper criticizes Lee Kuan Yew clique’s for doing America’s dirty work; Singapore becomes supply base for US Imperialist invasion [of Vietnam].”[37] Clearly, Singapore’s ties with the United States darkened China’s attitude toward the nation—but at the time, this did not present a major issue as neither side was compelled to explore closer relations.

The situation changed in 1969, when Nixon announced America’s goal to wind down its involvement in the Vietnam War and reduce its military presence in Asia. Singapore had to contend with real fears about the aftermath of US withdrawal, and began to reconsider its distance from China. “The [Nixon Doctrine] set the stage for Vietnamization, or the policy groundwork that culminated in the eventual US withdrawal from Vietnam,” and at the time was viewed as “a message to Asian nations to redraw their security parameters accordingly, particularly as the durability of American engagement in Asia was placed in sharp relief by the Soviet Union’s strategic advances into Asia.”[38] The forewarning that the British would be retracting their military presence in Southeast Asia by 1971, removing another layer of defense for Singapore and reducing the number of players in the region, compounded these concerns. This impending reduction in Western military presence forced Singapore to reconsider its priorities with respect to the balance of powers in the region. Most prominently, “the virtually concurrent announcement of the Nixon Doctrine and Brezhnev’s proposal for a collective security system in Asia provoked alarm in Singapore as an indication of a Soviet initiative to fill the vacuum likely to arise form America’s seeming strategic retreat.”[39] For their own national security reasons, both Singapore and China were concerned about the projection of Soviet influence in Southeast Asia. In fact,by the mid-1970s, “[Singapore had] identified the Soviet Union as the prime external threat to regional order.”[40] In the context of Sino-Soviet competition, the Soviet Union was also China’s largest competitor. Thus, for the first time, “Singapore found common tactical cause with China over the regional balance of power.”[41] This alignment could prove useful for the securing of common interests, but a shared enemy alone would not fundamentally bring these nations closer together.

The Sino-Soviet split set the stage for another key US development in the region that affected Singapore-China relations: US-China rapprochement, marked by the historic visit of President Nixon to China in 1972. US-China rapprochement shifted the Cold War balance of power away from the Soviet Union, for“by achieving a rapprochement with Washington, Beijing’s leaders drastically improved China’s strategic position vis-à-vis the Soviet threat.”[42] As a result, in Southeast Asia China came to be seen as more credible counterweight to the Soviet Union’s expansion, though it was still regarded with suspicion.Writing in 1973, Robert Horn analyzed Singapore’s position as follows: “Singapore, owing to its smaller size and greater vulnerability as well as to its predominantly Chinese population, has felt more strain than Malaysia in the face of China’s re-emergence, the Sino-American rapprochement and the US withdrawal, and is acutely concerned for its own security.”[43] In the face of China’s rising power, Singapore could afford neither to ignore China nor become its enemy, and was forced instead to consider a friendly foreign policy stance towards China.

US-China rapprochement and China’s increasing international influence also led, indirectly, to the opening of diplomatic channels between Singapore and Beijing. In October 1971, the People’s Republic of China gained control of the Chinese seat in the United Nations in a vote supported by Singapore, which had recognized the PRC as the legitimate China since independence. In the following years the United Nations would provide a forum for dialogue between Singapore and China. In fact, it was after Singaporean Foreign Minister Rajaratnam met his Chinese counterpart Qiao Guanhua at a dinner in New York that China extended an official invitation to Singapore to visit Beijing. Without US-China rapprochement, this meeting could hardy have occurred as it did. In fact, later on, Rajaratnam would point to Nixon’s visit as setting the precedent for his own.[44]

The Role of ASEAN: Regional Tensions and Neutralization

To understand Singapore’s concerns leading up to Rajaratnam’s visit, we must take a step back and examine the regional politics within Southeast Asia. While ethnic concerns posed an obstacle to Singapore’s normalization of diplomatic ties with China, strengthening relations became a necessary step to support Singaporean interests with respect to its neighbors. In 1967, Singapore became a founding member of ASEAN, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, along with Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia, and the Philippines. This step was seen as necessary for Singapore, because strengthened political and economic ties with these nations would bolster regional stability; however, Singapore remained acutely aware of its vulnerability with respect to the strength of its larger neighbors. Singapore was the only state outside China’s claimed borders with an ethnic Chinese majority, and thus faced suspicion from its neighbors that it would become a “third China” and act as a base of Chinese interest in the region. It was feared that Singapore’s Chinese population had not developed a national identity separate from China, and that in the event of closer ties between the two nations, “racial affinity [would] overcome political, social and economic differences between the Singapore and mainland Chinese,”[45] and hence Singapore “[would] be easily manipulated by China.”[46]

In order to stave off these criticisms, Singapore announced that it would become the last ASEAN nation to normalize ties with China. In particular, Singapore would wait until Indonesia—which had broken off ties with China in 1967 following the bloody anti-communist crackdown and regime change—had re-established ties with China before doing so itself. [47] The centrality of ASEAN to Singapore’s policy towards China is expressed in the analysis of Alex Josey, then the press secretary to Lee Kuan Yew: Singapore’s establishment of diplomatic relations with China could only be “viewed in terms of the reaction of other Southeast Asian nations.”[48]

These suspicions of Singapore reflect a broader Southeast Asian apprehension toward China, a stance tied directly to the perceived threat of Chinese-backed communist insurrection in the region. In the 1960s, the Chinese Communist Party provided ideological and political support to communist parties engaged in armed insurrection throughout Southeast Asia. These parties, including the Malayan Communist Party (MCP) and the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI) enjoyed close relationships with Beijing, and even maintained delegations in the Chinese capital.[49] It is no surprise that the Chinese state media opposed the formation of ASEAN in 1967, referring to the alliance as “an anti-Chinese, anti-Communist, and anti-Revolutionary alliance”, and characterizing ASEAN as “a neo-colonialist tool of US imperialism and Soviet revisionism in Asia.”[50] During this period, China began to explicitly pursue a policy of building state-to-state relations while still maintaining its ideological obligations to assist Communist parties in the region. By the mid-1970s, however, state-to-state relations rose in importance compared to party-to-party support; the CCP recognized that its dual policy was hindering its relations in the region.[51] Dick Wilson points to shift in official party rhetoric that reflects this change: in 1969, Lin Biao “pledged support specifically to Southeast Asian “armed struggles” in his report to the Ninth Congress of the Communist party”; by 1973, “Chou En-lai’s less extreme report to the Tenth Congress…referred only in general terms to the “just struggles of the third world.”[52] Despite this shift away from party-to-party relations, the CCP did not entirely dial down its ideological support for the Southeast Asian communist movement, establishing CCP-controlled pro-revolutionary radio stations in Malaysia and Burma in 1969 and 1971 respectively.[53]

This contradictory position presented a challenge to Southeast Asian states, including Singapore[54]—on the one hand, Chinese actions posed a threat, however vague, to their sovereignty, yet on the other, relations with China were increasingly desirable for economic interests and for securing a balance of power in the region. In 1974, Singaporean current affairs commentator Pang Cheng Lian described the Southeast Asian attitude towards China with this apt metaphor: “Southeast Asian nations are not exactly [rushing] into the arms of Peking. On the contrary, the picture that comes to mind is that of anxious moths attracted by a light and yet afraid of getting hurt if they get too close to it. If the light turns out to be a fire, the moth faces the risk of being burnt to cinders, but if it is an electric bulb, then everything is well.”[55]

One measure Southeast Asia took to protect regional interests and develop a strategy with respect to China was ASEAN’s proclamation of neutralisation in 1971. The Kuala Lumpur Declaration, signed by all five member states, declared the goal to establish “Southeast East as a Zone of Peace, Freedom and Neutrality, free from any form of manner of interference by outside Powers.”[56] The declaration also called on Southeast Asian nations to “make concerted efforts to broaden the areas of co-operation which would contribute to their strength, solidarity and closer relationships.”[57] Although on the surface this proposal seemed to be a general call for international non-involvement and regional cooperation, “the chief target of the neutralization proposal…[was] China.”[58] Indeed, neutralisation was a strategy explicitly oriented toward defining Southeast Asian relations with China. A Straits Times article quotes Indonesian Foreign Minister Adam Malik expressing this view with the rhetorical question, “How can we have neutralization in Southeast Asia without normalizing relations with China?”[59] As early as 1973, Southeast Asian nations had reached a consensus on the future desirability of relations with China.[60] In effect, the purpose of neutralization was not to prevent China’s interference in the region, but to control China’s inevitable influence.

In the eyes of Southeast Asia, China was a “sleeping giant,” poised in the following decades to significantly increase its presence in Southeast Asia—and it potentially stood to gain the greatest influence of any major power due to its historical, geographic, and economic ties to the region. By declaring their position and presenting a united front through regional cooperation, neutralisation allowed ASEAN nations to meet China on their own terms. Furthermore, strengthening economic and security ties within the region would reduce the latitude for external powers to interfere in Southeast Asia. This joint understanding among the states reduced the stress placed on any one bilateral relationship with China, and ensured that exploring relations with China would not become a point of contention within ASEAN. Thus, although Singapore’s official stance had not changed, the environment was more relaxed to explore every form of cooperation “short of physical exchange of diplomats” with China.[61] Other Southeast Asian nations, afforded some measure of protection against the Chinese threat by neutralization, went ahead with recognizing China. The first to do so was Malaysia, which formalized ties with China in 1974.[62] Establishing diplomatic relations would facilitate direct trade between other ASEAN nations and China, cutting out Singapore as a middleman in areas including rubber exports and reducing Singapore’s role as center for entrepôt trade.[63]

At this critical juncture, this economic threat was but one of Singapore’s concerns in an unstable regional environment: it also had to contend with the U.S. retreat from Southeast Asia, the increasing Soviet threat, and rising Chinese influence in the region. On both fronts of Singapore’s foreign policy goals—maintaining economic security and a balance of power—Singapore could no longer afford to ignore its relationship with China. As commentator Pang Cheng Lian noted,“whether the government likes it or not Singapore may have to take a stand soon on relations with China.”[64]

Minister Rajaratnam’s visit to China

In March 1975, Singaporean Foreign Minister S. Rajaratnam led a delegation to China on the “Singapore Goodwill Mission Visit,” breaking the diplomatic silence between the two countries for the first time. In visiting China, Rajaratnam was accepting an invitation extended to him by Chinese Foreign Minister Qiao Guanhua at a meeting in New York the year prior.[65] This diplomatic visit was the culmination of years of groundwork, coming at the heels of a series of exploratory transnational visits, including the Singapore China Chamber of Commerce trip in 1971, an exchange of ping-pong teams in 1972, and a Singapore Medical Association tour of China in the same year.[66] The visit was made possible by a mutual understanding that the two nations had shared economic and security interests, and that shifting international dynamics indicated that there was potential for a stronger relationship. Reflecting on his visit more than a decade later, Rajaratnam reveals a keen awareness of the role of international developments in bringing about this meeting. When asked in an interview about the motives of China’s invitation, he responded with a lucid summary:

“That was the time when developments in the international arena were becoming very complicated. China and Russia were engaged in acrimonious quarrels. China often accused Russia of hegemonism [sic]. At that time, the bad relations between China and American were becoming more cordial. This is evident from the special visit of President Nixon to Beijing to discuss the international situation with Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai. At that time, a new force in Southeast Asia, namely ASEAN, had been established eight years ago and Singapore was also a very important pivot in the communications between the East and the West. Perhaps another important reason was that, at that time, I had been to Moscow three times and Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew had also visited Russia. So I guess, in those circumstances, China wanted very much to know the direction of Singapore’s foreign policy.”[67]

Although the two sides shared a common goal to improve mutual understanding, they approached the visit from slightly different angles—Singapore’s main objective was to improve its economic links with China, while China was more curious to probe Singapore’s political outlook and strengthen diplomatic ties between the two nations. By the end of the trip, the two nations had reached a clear understanding of the other’s position and had set the stage for the mutually beneficial unofficial diplomatic relationship to follow. Initially, the Singaporean delegation did not know what to expect from its 10-day visit to Canton and Beijing, and “did not attach too high an expectation on [the] visit.”[68] Instead, Singapore’s strategy was to focus on a concrete objective: to improve trade ties with China. This strategy is reflected in the selection of delegates to accompany Rajaratnam—in addition to senior foreign affairs official Lee Koon Choy and the mission secretary, the five-member team was rounded out by the Chairman of the Port of Singapore Authority and the Development Bank of Singapore, Howe Yoon Chong, and Deputy Chairman of the Economic Development Board, I.F. Tang.[69] Trade matters also formed a large portion of Straits Times correspondent Peter Lim’s coverage of the events as a member of the press delegation, suggesting that trade developments were being closely followed back home.[70]

Figure 2. S. Rajaratnam shaking hands with Zhou Enlai. From People’s Daily Online.[71]

The Chinese officials, on the other hand, held a different set of motives—to determine the warmth of Singapore’s attitude towards China and dispel any ill will that would hinder future relations. As a result, they engaged in a charm offensive that took the Singaporean delegation by surprise. Rajaratnam noted with surprise the warm reception on the part of their Chinese hosts—beyond lavish accommodations and guided sightseeing tours, they even took pains to discover Rajaratnam’s favourite food—raw chillies—and serve a portion at every meal.[72] The clearest indication of the importance the Chinese placed on cultivating the relationship with Singapore came in the form of an unanticipated addition to Rajaratnam’s itinerary—a late night audience with Chinese head of government Zhou Enlai. Rajaratnam recalls being whisked away in the middle of the night to Zhou’s residence, where Zhou (in a state of ill health towards the end of his life) made a special effort to receive him.[73] Zhou’s priorities for this meeting are best revealed in the following passage that comprises Zhou’s journal entry for May 16, 1973:

“I met with the Singaporean Foreign Minister Rajaratnam and the high-level foreign ministry official Lee Khoon Choy. During the meeting, I said the following, “We respect your national sovereignty, for you are not the “Third China” but the Republic of Singapore. The Republic of Singapore is an independent nation with its own sovereignty.” I also said, “China hopes to establish diplomatic relations with Singapore in the near future, but if this poses trouble to Singapore, then postponing relations is not a problem, and we understand the situation. Please convey to your Prime Minister that China expresses thanks to Singapore for its policy of recognizing the PRC and not Taiwan following your independence, we appreciate this move on your part.” Finally, I conveyed that China supports ASEAN and Southeast Asia’s hopes for neutralization, for if the five ASEAN nations have peaceful relations, this will prevent the emergence of big power hegemony in the region.”[74]

This new expression of friendship towards Singapore represented a remarkable departure from China’s rhetoric in years prior: it contains an explicit recognition of Singapore’s independence, which China had refused to acknowledge until a tacit recognition in 1970; Zhou’s statement also reflects explicit support for ASEAN, which China had once excoriated and referred to as a “so-called alliance” in service of “US imperialism and Soviet revisionism.”[75] Significantly, Zhou’s message to Rajaratnam reflects an understanding and acceptance of Singapore’s policy line with respect to being the last ASEAN nation to normalise relations with China. In one fell swoop, Zhou cast aside many of the ideological obstacles that had once been a source of tension between the two nations. Rajaratnam, for his part, was careful not to rebuff this offer of friendship, making it clear to his hosts that he held “an open mind about future relations between Singapore and China” and was receptive to these Chinese overtures towards a diplomatic relationship.[76] However, “to prevent any misunderstanding,”[77] he also stressed that Singapore would maintain a measure of distance with China, and would follow its own national interests should they clash with those of China. For example, he made it a point to issue a warning about Singapore’s impending military training exercise in Taiwan to Qiao Guanhua, who “immediately indicated that he had taken note of what I said.”[78] With this statement, Rajaratnam expressed that a closer relationship with China in the future would necessarily be one on equal footing, and that Singapore would not compromise its own interests.

What did this trip achieve? Peter Lim, the Straits Times correspondent attached to the Singaporean delegation, lists two main achievements of the visit as follows: 1) “China’s expression of intentions to buy capital goods from Singapore in preference to other suppliers,” and 2) “[the] Agreement to exchange industrial missions as soon as possible…to explore possibilities of enlarging the scope for bilateral trade.”[79] Yet while these trade accomplishments were not insignificant, they were not the most enduring legacy of this visit nor its most path breaking achievement. This trip provided an expression of the Chinese extension of friendship to Singapore and Singapore’s subsequent acceptance, a development that was ten years in the making. It led directly to the visit of Lee Kuan Yew, Singapore’s Prime Minister, to China the year after and the establishment of de-facto friendly diplomatic ties between the two nations until official normalisation was achieved in 1990. After a decade of navigating tempestuous and unpredictable international waters, the 1975 Singapore Goodwill Mission set the relationship between Singapore and China on a new course.

Conclusion and Contemporary Implications

The period from 1965-75 marks the turbulent beginnings of the Singapore-China relationship. During this period, the two nations had not established diplomatic ties, and thus the development of relations between Singapore and China arose entirely in reaction to international events and the shifting dynamics of power among key regional players. The goal of this paper was to chart this development by systematically analysing the role of three major revolving players—the Soviet Union, the United States, and ASEAN—in shaping the Singapore-China relationship. From a position of distance and mutual distrust in 1965, international dynamics pushed the two nations together and at times pulled them apart: Sino-Soviet competition drove Chinese interest in Singapore, the Nixon Doctrine and US-China Rapprochement raised China’s role in Singapore’s balance of power concerns, and ASEAN played a key role in first hindering and then ultimately impelling Singapore to take steps towards China. The analysis of Rajaratnam’s 1975 visit provides an explicit illustration of the nature of Singapore-China relations by the end of the decade, revealing just how much had changed. More broadly, this paper represents an attempt to write Singapore into the history of the non-aligned world in Cold War. Singapore provides a fascinating example of the interaction and competition between the tri-polar Cold War powers as each sought to assert control in Southeast Asia; Singapore also occupies a unique position in relation to China and thus helps to illustrate the shift in China’s policies through this time period.

Finally, this paper has broader contemporary implications for the study of Singapore’s international affairs. Singapore is unique in that its foreign policy has remained largely consistent over the last several decades, due in part to the fact that Singapore’s security concerns are predicated on innate factors of geography and regional vulnerability. Furthermore, Singapore’s ruling party, the People’s Action Party, has remained in power since 1959. Thus, although the world order has changed, Singapore is navigating many of the same issues today as it did in the 1960s and 70s, particularly in relation to balancing of regional and world powers. Applying the framework of this paper to other periods in the history of Singapore-China relations will reveal a clearer picture of the relationship’s continuity and change over time, and provide background for a comprehensive understanding of present relations between the two countries.

The remarkable continuity in key factors underpinning Singapore-China relations is evident in the 2016 Terrex incident, in which nine Singaporean Terrex armoured vehicles were seized in Hong Kong and held for two months. Analysis of this incident suggests a direct connection to the issues discussed during Rajaratnam’s 1975 Singapore Goodwill Mission. The most obvious connection is that the vehicles were seized en route to Singapore returning from a join military exercise with Taiwan; more than 40 years before, Rajaratnam had stressed Singapore’s commitment to such joint exercises with Taiwan when he met with the leadership in Beijing. Although Singapore has maintained a policy of recognising the PRC as the one China, the joint military exercises with Taiwan have been interpreted as one way for Singapore to express a measure of independence from and resistance to Chinese political influence. [80] The incident also echoes decades-old conflict regarding Singapore’s apparent alignment with ASEAN over China; as I discussed earlier in this paper, Singapore faced challenges in the 60’s and 70’s to maintain geopolitical stability by balancing its loyalty to ASEAN neighbours and the demands of its relationship with China. Several months prior to the Terrex vehicle seizure, an international tribunal on South China Sea territorial claims ruled in favour of the Philippines over China; Singapore claimed neutrality, but PM Lee Hsien Loong’s remarks were seen by China as supportive of the ruling. Analysts widely interpreted the seizure of the vehicles not only as retaliation for Singapore’s military exercises with Taiwan, but also as an expression of the Chinese government’s disapproval of perceived Singaporean support for the Philippine’s rival territorial claims in the South China Sea.[81]

Although the significance of this incident is contested, some experts interpret the incident as a turning point, signalling that China is increasingly putting pressure on Singapore and trying to gain an upper hand in Singapore-China relations. Writing about the foreign policy implications of the incident, Alan Chong and David Han of the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies claim, “China has changed and Singapore must now exercise care so that its actions cannot be seized upon by its detractors as unfriendly acts vis-à-vis Chinese foreign policy.”[82] I would argue that Singapore has always “exercised care” in its relations with China, but it is certain that in today’s shifting landscape Singapore must pay increasingly close attention to navigating its relationship to China. The current focus in bilateral relations is illustrated by the topics discussed during a Singapore diplomatic mission to China in April 2019: US-China relations, regional issues related to trade agreements between ASEAN and China, and Singapore’s interests with respect to China’s expansion through the One Belt One Road initiative.[83]

Against shifts in world power played out on battlefields including the US-China trade war and the South China Sea, Singapore must adapt to face a new set of dynamics among the big powers and regional neighbours that have shaped Singapore’s foreign policy direction since independence. This necessitates a complicated balancing act between protecting Singapore’s vulnerabilities and advancing its national goals, largely in response to moves made by international actors and the US and China in particular. Some experts suggest that China’s recent rise in economic and military power might signal a tipping point in the balance of power from the US to China, particularly within Asia.[84] Whether or to what extent this is true remains to be seen, but Singapore will be watching as though its very life depends on it.

Image Source: The Straits Times

Bibliography:

Chan, Minnie. “How Singapore’s military vehicles became Beijing’s diplomatic weapon.” South China Morning Post, December 3, 2016.

Chen, Jian.“The Sino-American Rapprochement, 1969-1972.” In Mao’s China and the Cold War, 238-276. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

Chin, Kin Wah. “A New Phase in Singapore’s Relations with China.” In ASEAN and China: An Evolving Relationship, edited by Joyce K. Kallgren, Noordin Sopiee, and Soedjati Djiwandono. Berkeley: Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California, 1988.

Chong, Alan and David Han. “Foreign Policy Lessons from the Terrex Episode.” RSIS Commentary, no. 22 (2017).

Chun, Linda Yip Seong. Bibliography of ASEAN-China Relations. Singapore: ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute, 2006.

中共中央文献研究室编CPC Central Research Office. 周恩来年谱, 1949-1976 [Zhou Enlai Chronicles, 1949-1976].Beijing: 中共中央文献出版社, 1997.

Fook, Lye Liang. “Singapore-China Relations: Building Substantive Ties amidst Challenges.” Southeast Asian Affairs(2018): 321-340.

Gurtov, Melvin. “Sino-Soviet Relations and Southeast Asia: Recent Developments and Future Possibilities.” Pacific Affairs 43, no. 4 (1970): 491-505. doi:10.2307/2754901.

Horn, Robert. “Changing Soviet Policies and Sino-Soviet Competition in Southeast Asia.” Orbis 17, no. 2 (1973): 492-526.

Ho, Benjamin and Dylan Loh. “The Terrex Vehicles Issue: China Seizes Asia-Pacific Initiative.” RSIS Commentary, no. 315 (2016):2.

Hsinhua Correspondent. “Soviet Social-Imperialists Covet Southeast Asia: “Asian Collective Security System’ is a pretext for expansion.” Peking Review, August 15, 1975.

Josey, Alex. “Ties with China poser.” New Nation, September 15, 1971. NewspaperSG.

Latif, Asad-ul Iqbal. “Engaging the Powers.” In Between Rising Powers: China, Singapore and India, 26-46. Singapore: ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute, 2007.

Latif, Asad-ul Iqbal. “Tentative Encounters: China, India and Indochina.” In Between Rising Powers: China, Singapore and India, 47-82. Singapore: ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute, 2007.

Leifer, Michael. Singapore’s Foreign Policy : Coping with Vulnerability. Politics in Asia Series ; 25. London ; New York: Routledge, 2000.

Li, Danhui and Yafeng Xia.”Jockeying for Leadership: Mao and the Sino-Soviet Split, October 1961–July 1964.” Journal of Cold War Studies 16, no. 1 (2014): 24-60.

Lim, Peter. “Chou’s Hand of Friendship.” The Straits Times, March 18, 1975. NewspaperSG.

Lim, Peter. “It all began at a dinner in New York….” The Straits Times, March 14, 1975. NewspaperSG.

Lim, Peter. “Raja has Meeting with Chou.” The Straits Times, March 17, 1975. NewspaperSG.

Lim, Peter. “Talks very useful, says Raja.” The Straits Times, March 22, 1975, NewspaperSG.

Lim Yan Liang. “Suzhou Park A Hallmark Of Singapore-China Cooperation: DPM Teo Chee Hean.” The Straits Times, April 13, 2019. https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/east-asia/suzhou-park-a-hallmark-of-singapore-china-cooperation-dpm-teo

Liu Zhen. “Singapore-Taiwan military agreement to stay in place despite pressure from Beijing.” South China Morning Post, October 5, 2017.

Long, S.R. Joey. “Bringing the International and Transnational Back In: Singapore, Decolonisation, and the Cold War.” In Singapore in Global History, edited by Heng Derek and Aljunied Syed Muhd Khairudin, 215-34. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2011.

Pang, Cheng Lian. “China image in Singapore conjures up different things to different people.” New Nation, February 10, 1971. NewspaperSG.

Pang, Cheng Lian. “Normalising Relations with China.” New Nation, January 4, 1974.

Pang, Cheng Lian. “Singapore’s Dilemma: Peking’s Thaw Has Come Two Decades Too Soon.”New Nation, May 20, 1971. NewspaperSG.

People’s Daily. “美帝走狗的反革命小联盟” [“A Counter-Revolutionary Alliance of United States Lackeys”]. 人民日报(People’s Daily), August 12, 1967.

People’s Daily. “马来亚《阵线报》谴责李光耀傀儡集团为美帝效劳 新加坡已变成美帝侵越战争补给基地” [“Malayan newspaper criticizes Lee Kuan Yew clique’s for doing America’s dirty work; Singapore becomes supply base for US Imperialist invasion”]. 人民日报(People’s Daily), September 2, 1968.

People’s Daily.新加坡中华总商会工商业考察团离京前往我国南方访问” [“Singaporean Chinese Chamber of Commerce delegation visits the south of China”]. 人民日报(People’s Daily), October 27, 1971.

People’s Daily.”新加坡医学协会访华参观团到京”[“Singapore Medical Association visiting delegation arrives in Beijing”]. 人民日报(People’s Daily), April 11, 1972.

People’s Daily. 周恩来总理会见拉贾拉南外长”[Zhou Enlai meets Foreign Minister Rajaratnam]. 人民日报(People’s Daily), March 17, 1975.

Rajaratnam, S. and Ang Hwee Suan. Dialogues with S. Rajaratnam, Former Senior Minister in the Prime Minister’s Office. Shin Min Daily News Series. Singapore: Shin Min Daily News, 1991.

Singh, Bilveer. “Singapore-Soviet relations.” In The Soviet Union and the Asia-Pacific Region: views from the region, edited by Pushpa Thambipillai and Daniel C. Matuszewski, 112-122. New York: Praeger, 1989.

Soh, Tiang Keng. “Non-Alignment, Full Support for U.N. Basis of Foreign Policy: Raja.” The Straits Times, August 11, 1965.NewspaperSG.

Tan, Dawn Wei. “PM Lee Hsien Loong And Chinese Leaders Discuss Sino-US Relations, Belt And Road Cooperation And Smart Cities.”The Straits Times. April 29, 2019.

The Sraits Times. “Neutrality useless without ties with Peking.” The Straits Times, May 10, 1973.

The Straits Times. “We are most interested in China trade: Rajaratnam.” The Straits Times, August 21, 1965. NewspaperSG.

Wilson, Dick. The Neutralization of Southeast Asia. Praeger Special Studies in International Politics and Government. New York: Praeger, 1975.

[1]“美帝走狗的反革命小联盟” [“A Counter-Revolutionary Alliance of United States Lackeys”], 人民日报(People’s Daily), August 12, 1967.

[2]Lim Yan Liang, “Suzhou Park A Hallmark Of Singapore-China Cooperation: DPM Teo Chee Hean,” The Straits Times, April 13, 2019, https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/east-asia/suzhou-park-a-hallmark-of-singapore-china-cooperation-dpm-teo

[3]Linda Yip Seong Chun, Bibliography of ASEAN-China Relations (Singapore: ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute, 2006), 22-24.

[4]Bilveer Singh, “Singapore-Soviet relations,” in The Soviet Union and the Asia-Pacific Region: views from the region, ed. Pushpa Thambipillai and Daniel C. Matuszewski (New York: Praeger, 1989).

[5]See Robert Horn, “Changing Soviet Policies and Sino-Soviet Competition in Southeast Asia,” Orbis 17, no. 2 (1973); Robert C. Horn, “Moscow’s Southeast Asian Offensive, ” Asian Affairs 2, no. 4 (1975); and Robert C. Horn, “Soviet Influence in Southeast Asia: Opportunities and Obstacles.” Asian Survey 15, no. 8 (1975).

[6]Michael Leifer, Singapore’s Foreign Policy: Coping with Vulnerability(New York: Routledge, 2000), 1.

[7]Soh Tiang Keng, “Non-Alignment, Full Support for U.N. Basis of Foreign Policy: Raja,” The Straits Times, August 11, 1965.

[8]Leifer,Singapore’s Foreign Policy: Coping with Vulnerability, 34-35.

[9]Alex Josey, “The impact of Chairman Mao’s nuclear policy on the Republic of Singapore,” New Nation, May 17, 1971. NewspaperSG.

[10]Leifer,Singapore’s Foreign Policy: Coping with Vulnerability, 111.

[11]“We are most interested in China trade: Rajaratnam,” The Straits Times, August 21, 1965. NewspaperSG. This statement holds another silent contradiction: in 1965, China had not “[recognised] [Singapore’s] independence” and would not do so for several years; nonetheless, the Singaporean government was willing to embark on trade with China.

[12]John C. H. Wong, “The Role of China in Singapore and Southeast Asian Trade,” Southeast Asian Journal of Social Science 3, no. 1 (1975): 54.

[13]Robert Horn, “Changing Soviet Policies and Sino-Soviet Competition in Southeast Asia,” Orbis 17, no. 2 (1973): 514.

[14]Dick Wilson, The Neutralization of Southeast Asia (New York: Praeger, 1975), 129.

[15]Wong, “The Role of China in Singapore and Southeast Asian Trade,”51.

[16]Lye Liang Fook, “Singapore-China Relations: Building Substantive Ties amidst Challenges,” Southeast Asian Affairs(2018): 337.

[17]Asad-ul Iqbal Latif, “Engaging the Powers,” in Between Rising Powers: China, Singapore and India (Singapore: ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute, 2007), 30.

[18]Latif, “Engaging the Powers,” 29.

[19]Ibid, 33.

[20]Robert Horn, “Changing Soviet Policies and Sino-Soviet Competition in Southeast Asia,” Orbis 17, no. 2 (1973): 493.

[21]Bilveer Singh, “Singapore-Soviet relations,” in The Soviet Union and the Asia-Pacific Region: views from the region, ed. Pushpa Thambipillai and Daniel C. Matuszewski (New York: Praeger, 1989), 113.

[22]Ibid.

[23]Ibid.

[24]Danhui Li and Yafeng Xia,”Jockeying for Leadership: Mao and the Sino-Soviet Split, October 1961–July 1964,” Journal of Cold War Studies 16, no. 1 (2014): 26.

[25]Horn, “Changing Soviet Policies and Sino-Soviet Competition in Southeast Asia,” 496.

[26]Ibid.

[27]Melvin Gurtov,”Sino-Soviet Relations and Southeast Asia: Recent Developments and Future Possibilities.” Pacific Affairs 43, no. 4 (1970): 496.

[28]Ibid, 497.

[29]Hsinhua Correspondent,” Soviet Social-Imperialists Covet Southeast Asia: “Asian Collective Security System’ is a pretext for expansion,” Peking Review, August 15, 1975, 20.

[30]Asad-ul Iqbal Latif, “Tentative Encounters: China, India and Indochina,” in Between Rising Powers: China, Singapore and India (Singapore: ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute, 2007), 51-52.

[31]Pang Cheng Lian, “Singapore’s Dilemma: Peking’s Thaw Has Come Two Decades Too Soon,” New Nation, May 20, 1971. NewspaperSG.

[32]See the contrast between the following two titles:

“‘马来亚革命之声’揭露李光耀傀儡集团迫害工人, 新加坡工人阶级坚持斗争必将推翻黑暗统治” [“The ‘Voice of Malayan Revolution’exposes the Lee Kuan Yew clique’s exploitation of workers; the workers of Singapore must persist in the struggle to overturn reactionary rule”], 人民日报(People’s Daily), January 23, 1970.

“中国和新加坡乒乓球运动员举行友谊赛” [“Chinese and Singapore ping pong players meet in friendly match”],人民日报(People’s Daily), July 13, 1972.

[33]“新加坡中华总商会工商业考察团离京前往我国南方访问”[“Singaporean Chinese Chamber of Commerce delegation visits the south of China”],人民日报(People’s Daily), October 27, 1971.

[34]Singh, “Singapore-Soviet relations,” 113.

[35]Leifer, Singapore’s Foreign Policy: Coping with Vulnerability, 46.

[36]Ibid.

[37]“马来亚《阵线报》谴责李光耀傀儡集团为美帝效劳 新加坡已变成美帝侵越战争补给基地” [“Malayan newspaper criticizes Lee Kuan Yew clique’s for doing America’s dirty work; Singapore becomes supply base for US Imperialist invasion”], 人民日报(People’s Daily), September 2, 1968.

[38]Latif, “Tentative Encounters: China, India and Indochina,” 49.

[39]Latif, “Engaging the Powers,” 44-45.

[40]Leifer, “Singapore’s Foreign Policy : Coping with Vulnerability”, 123.

[41]Ibid, 115.

[42]Jian Chen, “The Sino-American Rapprochement, 1969-1972”, in Mao’s China and the Cold War(Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2010), 239.

[43]Robert Horn, “Changing Soviet Policies and Sino-Soviet Competition in Southeast Asia,” Orbis 17, no. 2 (1973): 513.

[44]S.Rajaratnam, and Ang Hwee Suan. Dialogues with S. Rajaratnam, Former Senior Minister in the Prime Minister’s Office.Shin Min Daily News Series. (Singapore: Shin Min Daily News, 1991), 106.

[45]Pang Cheng Lian, “China image in Singapore conjures up different things to different people,” New Nation, February 10, 1971. NewspaperSG.

[46]Chin Kin Wah, “A New Phase in Singapore’s Relations with China,” in ASEAN and China: An Evolving Relationship, ed. Joyce K. Kallgren, Noordin Sopiee, and Soedjati Djiwandono, (Berkeley: Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California, 1988), 277.

[47] Fook, “Singapore-China Relations: Building Substantive Ties amidst Challenges,” 22.

[48]Alex Josey, “Ties with China poser,” New Nation, September 15, 1971. NewspaperSG.

[49]Peter Lim, “Peking is so frank—in its own way,” The Straits Times, April 2, 1975, NewspaperSG.

[50]“美帝走狗的反革命小联盟” [“A Counter-Revolutionary Alliance of United States Lackeys”], 人民日报(People’s Daily), August 12, 1967.

[51]Pang Cheng Lian, “Normalising Relations with China,” New Nation, January 4, 1974, NewspaperSG.

[52]Wilson, The Neutralization of Southeast Asia, 118.

[53]Ibid, 117.

[54]The Malayan Communist Party saw no distinction between Singapore and Malaysia; a 1970 broadcast by the Voice of Malayan Revolution, a CCP-backed radio station, called for Singaporean workers to rise up and struggle against Lee Kuan Yew’s regime. See:“马来亚革命之声”揭露李光耀傀儡集团迫害工人—新加坡工人阶级坚持斗争必将推翻黑暗统治”[“The ‘Voice of Malayan Revolution’exposes the Lee Kuan Yew clique’s exploitation of workers; the workers of Singapore must persist in the struggle to overturn reactionary rule”], 人民日报(People’s Daily), Jaunary 23, 1970.

[55]Pang Cheng Lian, “Normalising Relations with China,” New Nation, January 4, 1974, NewspaperSG.

[56]Wilson, The Neutralization of Southeast Asia, 199.

[57]Ibid.

[58]Ibid, 116.

[59]Neutrality useless without ties with Peking.” The Straits Times, May 10, 1973, NewspaperSG.

[60]Ibid.

[61]Peter Lim, “It all began at a dinner in New York…,” The Straits Times, March 14, 1975, NewspaperSG.

[62]Leifer,Singapore’s Foreign Policy: Coping with Vulnerability, 112.

[63]Wong, “The Role of China in Singapore and Southeast Asian Trade,”59.

[64]Pang Cheng Lian, “Singapore’s Dilemma: Peking’s Thaw Has Come Two Decades Too Soon,”New Nation, May 20, 1971. NewspaperSG.

[65]Peter Lim, “It all began at a dinner in New York…,” The Straits Times, March 14, 1975, NewspaperSG.

[66]“新加坡医学协会访华参观团到京”[“Singapore Medical Association visiting delegation arrives in Beijing”], 人民日报 (People’s Daily), April 11, 1972.

[67]S. Rajaratnam, and Ang Hwee Suan. Dialogues with S. Rajaratnam, Former Senior Minister in the Prime Minister’s Office, 108.

[68]Ibid, 109.

[69]Peter Lim, “Raja has Meeting with Chou,” The Straits Times, March 17, 1975, NewspaperSG.

[70]Peter Lim, “Chou’s Hand of Friendship,” The Straits Times, March 18, 1975, NewspaperSG.

[71]“周恩来总理会见拉贾拉南外长” [Zhou Enlai meets Foreign Minister Rajaratnam], 人民日报 (People’s Daily), March 17, 1975.

[72]S.Rajaratnam, and Ang Hwee Suan. Dialogues with S. Rajaratnam, Former Senior Minister in the Prime Minister’s Office, 100.

[73]Ibid, 116.

[74]中共中央文献研究室编[CPC Central Research Office], 周恩来年谱, 1949-1976 [Zhou Enlai Chronicles, 1949-1976], (Beijing: 中共中央文献出版社, 1997), 700.

[75]“美帝走狗的反革命小联盟” [“A Counter-Revolutionary Alliance of United States Lackeys”], 人民日报(People’s Daily), August 12, 1967.

[76]S. Rajaratnam, and Ang Hwee Suan. Dialogues with S. Rajaratnam, Former Senior Minister in the Prime Minister’s Office, 110.

[77]Ibid, 100.

[78]Ibid.

[79]Peter Lim, “Talks very useful, says Raja,” The Straits Times, March 22, 1975, NewspaperSG.

[80]Liu Zhen, “Singapore-Taiwan military agreement to stay in place despite pressure from Beijing,” South China Morning Post, October 5, 2017.

[81]Minnie Chan, “How Singapore’s military vehicles became Beijing’s diplomatic weapon,” South China Morning Post, December 3, 2016.

[82]Alan Chong and David Han, “Foreign Policy Lessons from the Terrex Episode,” RSIS Commentary, no. 22 (2017):,3-4.

[83]Tan Dawn Wei, “PM Lee Hsien Loong And Chinese Leaders Discuss Sino-US Relations, Belt And Road Cooperation And Smart Cities,” The Straits Times. April 29, 2019.

[84]Benjamin Ho and Dylan Loh, “The Terrex Vehicles Issue: China Seizes Asia-Pacific Initiative,” RSIS Commentary, no. 315 (2016):2.