Introduction

Foreign service is a quintessentially “greedy job” – a demanding career with the biggest promotions coming when a diplomat completes several overseas tours.

The term “greedy work” wasn’t coined by Harvard Professor Claudia Goldin.1 But it has become widely popular thanks to the recognition, in 2023, of her groundbreaking research on women’s labor market outcomes by the Nobel Committee in economics. “Greedy jobs” are jobs that often pay very well but require that a person “works a greater number of hours or has less control over those hours.”2 Since greedy jobs like foreign service demand that employees prioritize work over other responsibilities, they disadvantage women who carry a disproportionate burden of family caregiving duties.

When I joined the Foreign Ministry of Kazakhstan almost two decades ago, there was just a handful of women career diplomats. Today the situation reflects a modest improvement: women make up just over 18% of the country’s Foreign Service. Yet, despite the progress, the picture at the top is stark: women’s miniscule representation in high-ranking and decision-making roles reveals a pronounced and persistent gender gap in the country’s Foreign Service.

Gender and Political Appointees

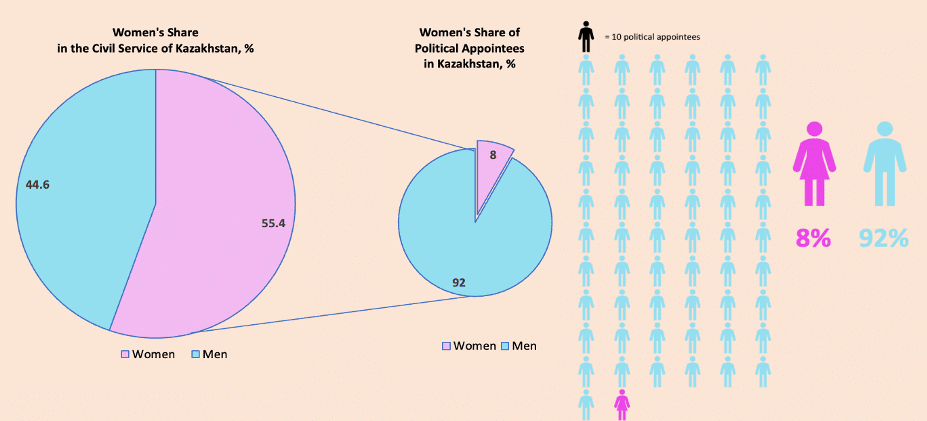

This trend is not unique to the Foreign Ministry but reflects a systemic issue within the entire civil service, where political appointees, i.e. government officials appointed by the President, are overwhelmingly male. In 2022, out of 726 political appointees there were only 59 women, or 8%.3 This is despite the fact that women comprise 55.4% of the civil service (Figure 1) and hold higher university degree attainment rates. Moreover, women serving in executive roles across all sectors of the Kazakh economy account for 42% and 47% in quasi-public bodies.

Figure 1. Women in the Civil Service of Kazakhstan

Foreign Service has historically been very much a man’s world. There are currently 15 women serving as ambassadors to the UN from their respective countries.4 With 193 UN member nations total, women make up just over 7% of ambassadors to the UN.5

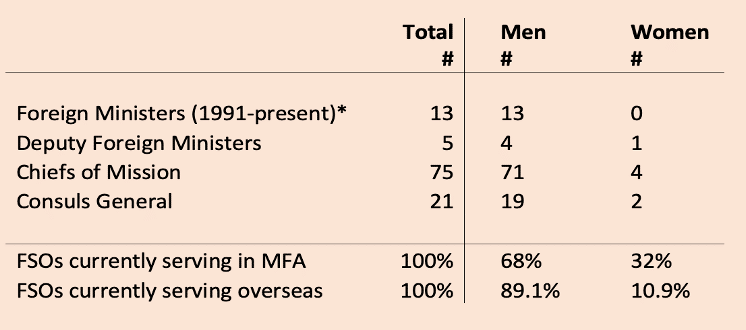

Not surprisingly, Foreign Service in Kazakhstan is mostly male-dominated; there has never been a woman foreign minister since Kazakhstan became independent in 1991. Since the beginning of Kazakhstan’s diplomatic relations with the rest of the world as a sovereign nation, Kazakh ambassadors have overwhelmingly been men. Currently only four women hold the chief-of-mission positions out of 75. Out of 21, only two women are serving in the position of a general consul.

Table 1. Women in the Foreign Service of Kazakhstan

Inside the Foreign Ministry, the gender imbalance in senior positions has significantly deteriorated in recent years. There are two committees and 17 bureaus inside the Ministry. None of them is led by a woman.6

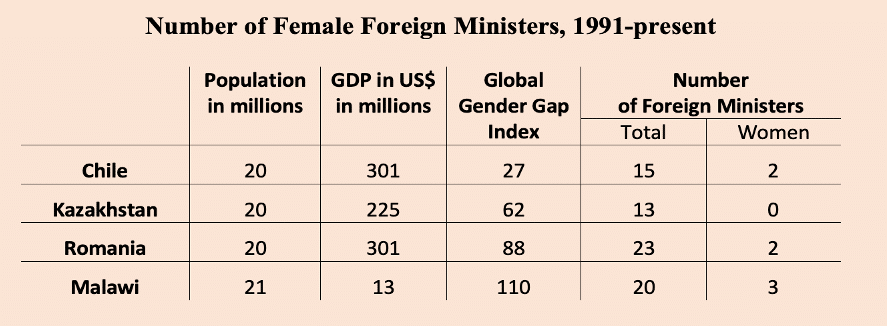

Table 2 compares Kazakhstan with three countries in Latin America, Eastern Europe and Africa of commensurate population and economy size, with exception of Malawi. Kazakhstan stands out with its absence of a female foreign minister, notwithstanding its higher gender equality ranking than Romania and Malawi.

Table 2. Country Profiles: Population, GDP, Gender Equality, and Diplomatic Continuity

Barriers and Repercussions of Gender Disparity in Foreign Service

Are fewer women promoted to leadership roles because they don’t strive or choose not to compete for higher positions, or because they need additional support, training, and professional development to succeed?

The underrepresentation of women in leadership positions in diplomacy may be due to a combination of factors, including personal choice. In the backdrop of a resurgent ethnic Kazakh identity, its traditional family values and rising religiosity, some women may choose not to compete for higher-ranking positions due to factors such as work-life balance, family priorities, or a lack of interest.

After all, overseas diplomatic assignments mean working unpredictable hours and are not compatible with being the person who does the school pick-up and drops everything when a child falls off a swing on the school playground in the middle of a high-level official visit. Goldin’s research sheds light on how motherhood necessitates more flexible work arrangements – anathema to the “greedy”, inflexible hours required of a diplomat serving overseas. Thus, “the motherhood penalty” in the foreign service is one of the highest.7

Research also suggests that women in the Foreign Service face systemic barriers, such as unconscious biases, gender stereotypes, and overt discriminatory practices.8 With limited access to networking and promotion opportunities, these cultural and institutional barriers make it more difficult for female diplomats to advance in their careers. Research studies also indicate that women are less likely to initiate negotiations to access desired positions.9

When I joined the Foreign Service back in the early 2000s, women were required to resign when they got married to fellow foreign service officers (FSOs), even though there was no written regulation that obligated them to do so. The policy was illegal, and yet it was faithfully followed. I am glad it is no longer enforced.

The bias against women, especially in overseas assignment and promotion procedures, today is more subtle.10 Some ambassadors are still under the assumption that women are less capable of handling the challenges of serving in a foreign country, such as dealing with security risks or cultural differences. Others outright object to a woman being posted to their embassies, especially in the Middle East and East Asia, in the name of working effectively in the country. As a result, women comprise less than 11% of Kazakh FSOs currently posted overseas.

The denial of opportunities to serve overseas has significant implications for women’s prospects for promotion and career growth. Serving in an overseas post is often a key requirement for career advancement in diplomacy, as it provides valuable experience in cross-cultural communication, negotiation, and leadership. Without these experiences, women FSOs face difficulties in demonstrating the skills and competencies needed for promotion to higher-ranking positions. This leads to a cycle of limited opportunities and slower career growth, which ultimately results in fewer women in leadership positions in the Foreign Service. Because women are consistently denied more powerful and influential positions in the diplomatic corps, Kazakhstan’s Foreign Ministry is now facing an impending spike in attrition among senior female career diplomats, and it ought to give its leadership a serious pause.

A more profound consequence is a foreign service that is not benefiting from the full strength of the country it represents. A study of OECD data conducted by Moody’s Analytics has found that global economy loses about US $7 trillion because of persisting gender discrimination in the workforce and managerial roles. It argues that increasing the share of female managers and professionals could “unlock higher economic prosperity.”11 This suggests that if Kazakhstan’s Foreign Ministry leveraged the untapped potential of female career diplomats in leadership roles, it could lead to an increase in its overall productivity and diplomatic effectiveness.

Policy Recommendations

To effectively combat the persistent gender gap and foster meaningful progress towards gender equality in the Foreign Service, there are specific, actionable steps that can be taken.

Establish A Study Commission: The Foreign Ministry should create a commission or contract with an outside organization to study the gender problem holistically. Such a commission should begin by collecting detailed attrition data on female FSOs and conducting exit interviews to better understand the factors leading to attrition and retention. Anonymous surveys should also be piloted among women in the Foreign Service to expose the widespread forms of overt and non-overt biases and determine what policy response is required.

Promote Work-Life Balance: There is an urgent need for the Foreign Ministry to undertake concerted efforts to carefully unearth the internal factors that impede progress by women and develop thoughtful policies to overcome them. These should be progressive work-life balance and family-friendly policies because the caregiver bias hurts women’s career advancement such as flexible working hours or results-based work schedules to allow employees the freedom to design their work time.

Ensure Spousal Employment: As Goldin puts it, “in a world of greedy jobs, couple equity is expensive” and in patriarchal societies like Kazakhstan flipping gender norms that assign the childcare responsibility solely to mothers comes with significant challenges, sacrifices, and social costs.12 As a result, a trailing spouse husband willing to put his own career on a back burner is a rarity in the Kazakh Foreign Service. This is why additional type of assistance is needed to tackle a problem that directly affects women diplomats: spousal employment overseas.

Introduce Gender-Parity Mandates: Gender-parity mandates should apply to executive roles in the public sector. Norway and the EU provide excellent leadership with their trailblazing legal requirements for a 40% female representation on corporate boards.13, 14

Conclusions

Women in high-level positions can offer unique perspectives based on their diverse experiences. A more diverse Foreign Service that reflects Kazakhstan will result in enhanced policymaking, reporting, and analysis. In a democratic society that Kazakhstan strives to be, senior government roles should be accessible to all citizens and reflect the country’s demographics. A bureaucracy that mirrors society will better represent its citizens and also will gain in legitimacy.

- Lewis A. Coser, “The housewife and her “greedy family,” in Greedy institutions: Patterns of undivided commitment (Free Press; New York: 1974) 89–100. ↩︎

- Gretchen Gavett, “The Problem with ‘Greedy Work,'” Harvard Business Review, September 28, 2021, https://hbr.org/2021/09/the-problem-with-greedy-work. ↩︎

- Bureau of National Statistics of Kazakhstan, “The Women and Men of Kazakhstan, 2018-2022,” accessed February 27, 2024, https://stat.gov.kz/upload/iblock/ca0/8dwtai8z61o7xt7ed8byhsp832np7u08/%D0%A1-16-%D0%93-2018-2022%20(%D0%B0%D0%BD%D0%B3%D0%BB).pdf ↩︎

- United Nations, “List of Permanent Representatives and Observers to the United Nations in New York,” accessed February 27, 2024, https://www.un.org/dgacm/sites/www.un.org.dgacm/files/Documents_Protocol/headsofmissions.pdf. ↩︎

- United Nations, “List of Permanent Representatives and Observers to the United Nations in New York.” ↩︎

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Kazakhstan, “Structure of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Kazakhstan,” accessed March 5, 2024, https://www.gov.kz/memleket/entities/mfa/about/structure/2/1?lang=en. ↩︎

- Zuzana Fellegi, Katerina Koci, and Klara Benesova, “Work and Family Balance in Top Diplomacy: The Case of the Czech Republic,” Politics & Gender 19, no. 1 (March 2023): 220–46. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X21000489. ↩︎

- Fellegi, Koci, and Benesova, “Work and Family Balance in Top Diplomacy: The Case of the Czech Republic.” ↩︎

- Hannah Riley Bowles, Linda Babcock, and Lei Lai, “Social Incentives for Gender Differences in the Propensity to Initiate Negotiations: Sometimes It Does Hurt to Ask,” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 103, no. 1 (2007): 84–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2006.09.001. ↩︎

- Matthew Connelly and Patricia Irvin, “How Secrecy Limits Diversity,” Foreign Affairs, May 12, 2023, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/how-secrecy-limits-diversity. ↩︎

- Dawn Holland and Katrina Ell, “Close the Gender Gap to Unlock Productivity Gains,” Moody’s Analytics, March 2023, https://www.moodysanalytics.com/-/media/article/2023/Close-the-Gender-Gap-to-Unlock-Productivity-Gains.pdf. ↩︎

- Claudia Dale Goldin, Career & Family: Women’s Century-Long Journey Toward Equity, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2021), 13. ↩︎

- Reuters, “Norway Proposes 40% Gender Quota for Large and Mid-Size Unlisted Firms,” Reuters, June 19, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/markets/europe/norway-proposes-40-gender-quota-large-mid-size-unlisted-firms-2023-06-19/. ↩︎

- Olivia Peluso, “The EU Will Soon Require 40% Gender Representation On Company Boards, But Where Does The U.S. Stand On Gender Equity In Boardrooms?” Forbes, June 9, 2022, https://www.forbes.com/sites/oliviapeluso/2022/06/09/the-eu-will-soon-require-40-gender-representation-on-company-boards-but-where-does-the-us-stand-on-gender-equity-in-boardrooms/?sh=2ab35ce42705. ↩︎