Home to more than 18,000 islands and 1,000 ethnicities, Indonesia takes pride in its national motto ‘unity in diversity.’ For its ethnic Chinese minorities, however, this phrase rings hollow. The Chinese-Indonesian community has been treated as a scapegoat for the country’s economic woes ever since the 1998 Asian Financial Crisis. This crisis that spiraled into mass violence against Chinese communities still pervades society’s collective memory: almost 1,000 killed, 87 women raped, and numerous businesses looted.1 Twenty-five years later, it remains unclear who is responsible – and public polling still shows that Indonesia’s majority considers the Chinese community as having “too much influence in the economy.”2

Anti-Chinese sentiment in Indonesia is historically rooted in the segregated society created by Dutch colonialism, in which the Chinese community received special treatment as tax collectors for native agricultural products.3 This social envy persisted as the Chinese minority dominated the private economy during President Soeharto’s era. At the same time, Soeharto enforced an assimilation policy to make the Chinese more ‘Indonesian’ and patriotic, which led to them becoming second-class citizens: Chinese cultural displays were banned and they required citizenship cards, unlike other ethnicities.4 Although state-sponsored racial discrimination is abolished today, the Chinese community still faces a long road to full integration. This will continue if the country acts in a transactional manner with its minority groups, with next year’s election being a focal point in this relationship.

The Battle of Identities in Indonesia’s 2024 Election

Who will the world’s third largest democracy choose in the polls this year?

For the majority of Indonesians, it is never an easy answer. All three candidates carry their own baggage: Anies Baswedan is the former Jakarta Governor who contributed to rising anti-Chinese tensions in the 2017 Jakarta Governor’s election, driven by his conservative Muslim supporters. Prabowo Subianto is a former lieutenant general who was accused of instigating anti-Chinese violence in 1998 and for violating human rights.5 He has twice lost in previous presidential elections, but now serves as Defense Minister. Ganjar Pranowo is the former Central Java Governor, largely considered a ‘puppet’ to his (incumbent) party oligarchs.

For the Chinese community, elections are candidates’ race to score diversity and inclusion points. Last September, Baswedan attended an event with the Indonesian-Chinese Community (KOMIT). In the 2019 election, Subianto also visited the North Sumatra province to engage with Chinese businessmen. As soon as the election cycle is over, however, this minority group’s plight is all but forgotten.

Unlike the clear-cut polarization found within U.S. politics, Indonesia’s political ideologies are rather fluid. This suggests that candidates’ ideas or policy prescriptions are not the political commodity; their identities are. While this is true for most Indonesian voters who prefer particular identities for their leaders (i.e. Muslim-Javanese men), the Chinese community does not show any political inclinations.6 Therefore, with current electability rankings placing Subianto first at 37%, Pranowo at 35.2%, and Baswedan at 22.7%, Chinese’s swing votes – 3% of population – can crucially impact the margin.7

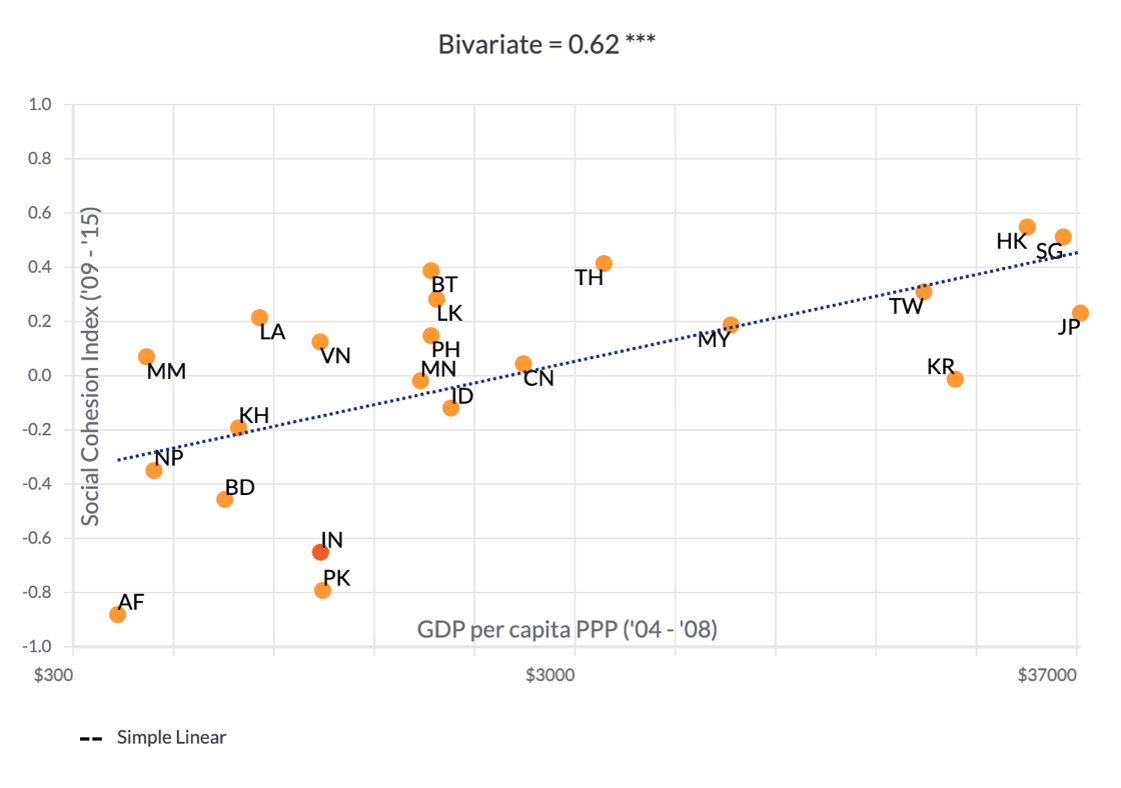

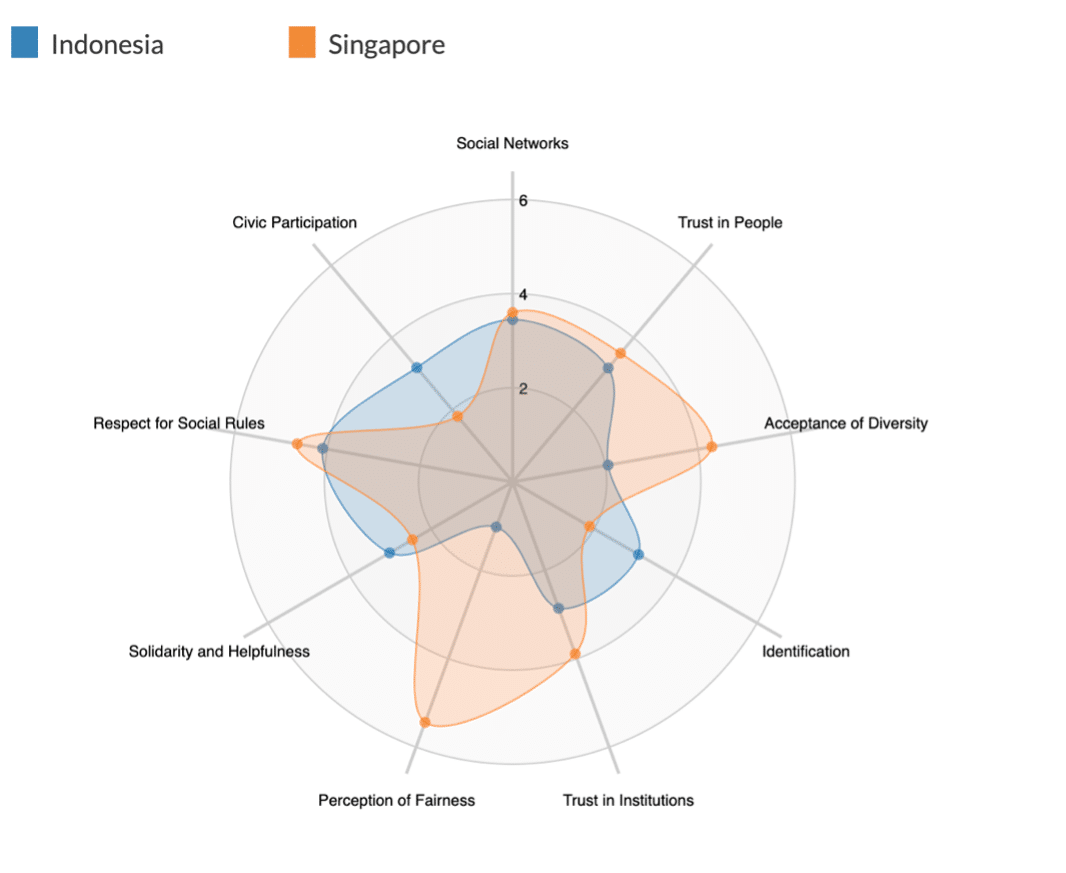

However, this transactional manner of interacting with minorities risks delaying the Chinese community’s integration into Indonesian society. To understand what is at stake, refer to Figures 1 and 2 that show a positive correlation between social cohesion and GDP per capita.8 Compared to Singapore, which sits on the higher end of the regression line, Indonesia scores significantly lower in acceptance of diversity and perception of fairness.

This should indicate to candidates that racial segregation may hamper growth. The future administration should commit to solving this racial sentiment, which Benjamin Bowser argues takes place simultaneously at the cultural, institutional, and individual levels.9

Putting Judicial Closure on Past Violations

At the institutional level, the Indonesian government should show that racial bias is no longer rooted in its agencies. Earlier this year, the incumbent President Joko Widodo acknowledged ‘gross human rights violations’ in the country’s history, including mass violence against Chinese Indonesians during the 1998 riot.10 This is progress that the Chinese community has long awaited, particularly after the initial inquiry stalled as investigators failed to find hard evidence of military involvement.11 However, the government’s plan for a non-judicial mechanism through involving a mere investigative team may result in unjust closure for the Chinese community.

Various forms of human rights violations require different settlement approaches. For example, South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) serves restorative justice rather than punitive justice – partly due to its limited resources to prosecute all perpetrators of apartheid and identify many victims, and due to an urgent need for a unified democratic transition.12 However, the 1998 riot requires punitive justice through judicial mechanisms to assert the government’s commitment to the rule of law.13 This incident is less politically sensitive and victims are known, making it more feasible for the next administration to bring accountability to the grieving families.

Fixing the Zero-Sum Game Perception in Society

At the individual level, Indonesian society should enable the Chinese community to participate in building trust and empathy – the currency for integration. Today, Lunar New Year is an Indonesian national holiday while Confucianism – locally known as ‘Konghucu’ – has been recognized as one of the country’s six religions. However, the current administration has not significantly improved the Chinese community’s standing in a society that largely sees them as a ‘threat’ in this zero-sum game. Growing Islamic conservatism in Indonesia exacerbates this religious framing issue, with 42% of Chinese community professing Christianity and 52% Buddhism and Confucianism.14

This poses a unique challenge when considered against well-known systemic racism in the U.S. that dates back to slavery and the Jim Crow era. For Indonesia, a nationwide anti-racism movement like the Black Lives Matter in the U.S. or the election of a president from a minority group has yet to happen. Racial discrimination is widely recognized in the U.S., but not so much in Indonesia where the struggle for independence shaped collective identity. It is also harder to mobilize empathy as anti-Chinese sentiment in Indonesia stems from an unequal society that puts the community at advantage, while the U.S. remains deeply rooted in slavery and economic oppression.

This suggests that the next president has to work on two things to fix the zero-sum game perception in Indonesian society. First, educating people to recognize racial bias and understand the danger if it continues. Second, to build empathy, there should be room for the Chinese community to play a role in society – to share their knowledge, work ethic, and ways to success to help native Indonesians thrive in the economy. Additionally, the government needs to provide ethnic Chinese more opportunities to expand out of just the business or trade sectors, including to the military, police forces, judiciary, or parliament.

Benedict Anderson writes that a nation is an ‘imagined community’ – it is imagined by the people who perceive themselves as part of the group despite never knowing nor seeing one another.15 However, the Chinese community will not be able to see themselves as part of the group when trust is not built and ‘Indonesian’ as an identity is not shared. This gap between the Chinese community and the rest of society should make people think about what this nation has not provided for them. For the Chinese community, the answer may lie in the enactment of justice towards their long-missing family members. For the rest of Indonesian society, it may be the provision of opportunities to help them and the economy flourish. Whatever the solution may be, the next president has a lot of work to do with respect to national integration.

- John Glionna, “In Indonesia, 1998 Violence Against Ethnic Chinese Remains Unaddressed,” Los Angeles Times, July 4, 2010, https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2010-jul-04-la-fg-indonesia-chinese-20100704-story.html. ↩︎

- ISEAS Yusof-Ishak Institute, The Indonesia National Survey Project: Engaging with Developments in the Political, Economic, and Social Spheres, (Singapore: ISEAS Publishing, 2023): 46–47. ↩︎

- Bryan Bilven, Boglárka Nyúl, and Anna Kende, “Exclusive Victimhood, Higher Ethnic and Lower National Identities Predict Less Support for Reconciliation Among Native and Chinese Indonesians through Mutual Prejudice,” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 91, (2022): 262–273. ↩︎

- Randy Mulyanto, “Chinese Indonesians Reflect on Life 25 Years from Soeharto’s Fall,” Al Jazeera, May 24, 2023, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/5/24/chinese-indonesians-reflect-on-life-25-years-from-soehartos-fall. ↩︎

- Tonny, “Prabowo and His Anti-Chinese Past?” New Mandala, June 27, 2014, https://www.newmandala.org/i-wanna-riot/. ↩︎

- Aisyah Llewellyn, “Are Chinese-Indonesian Voters Key to Prabowo’s Election Win?” Al Jazeera, April 15, 2019, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/4/15/are-chinese-indonesian-voters-key-to-prabowos-election-win. ↩︎

- Rabu, “Electability Ranks for Three Presidential and Vice Presidential Candidates from Various Survey Institutions,” CNN Indonesia, October 25, 2023, https://www.cnnindonesia.com/nasional/20231024185645-617-1015403/data-elektabilitas-3-capres-cawapres-dari-berbagai-lembaga-survei. ↩︎

- “Social Cohesion in Asia,” Bertelsmann Stiftung, https://www.bertelsmann-stiftung.de/de/unsere-projekte/deutschland-und-asien/social-cohesion-asia/social-cohesion-country-results. ↩︎

- Benjamin Bowser, “Racism: Origin and Theory,” Journal of Black Studies, 48 no.6 (2017): 572–590. ↩︎

- Ananda Teresia, “Jokowi regrets Indonesia’s bloody past, victims want accountability,” Reuters, January 11, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/indonesia-president-says-strongly-regrets-past-rights-violations-country-2023-01-11/. ↩︎

- Glionna, “In Indonesia, 1998 violence against ethnic Chinese remains unaddressed.” ↩︎

- Bronwyn Leebaw, “Legitimation or Judgement? South Africa’s Restorative Approach to Transitional Justice,” Polity 36, no.1 (2003): 56–75. ↩︎

- Suparman Marzuki and Mahrus Ali, “The Settlement of Past Human Rights Violations in Indonesia,” Cogent Social Sciences, 9, no. 1 (2023). ↩︎

- Taufiq Tanasaldy, “From Official to Grassroots Racism: Transformation of Anti-Chinese Sentiment in Indonesia,” The Political Quarterly 93, no. 3 (2022): 460–468. ↩︎

- Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (New York: Verso, 1991), 40. ↩︎